Barrow Study Shows How Nicotine May Promote Brain Aneurysm Rupture

A recent Barrow Neurological Institute study published in Stroke has identified how nicotine may enable the rupture of these blood vessel abnormalities under certain circumstances.

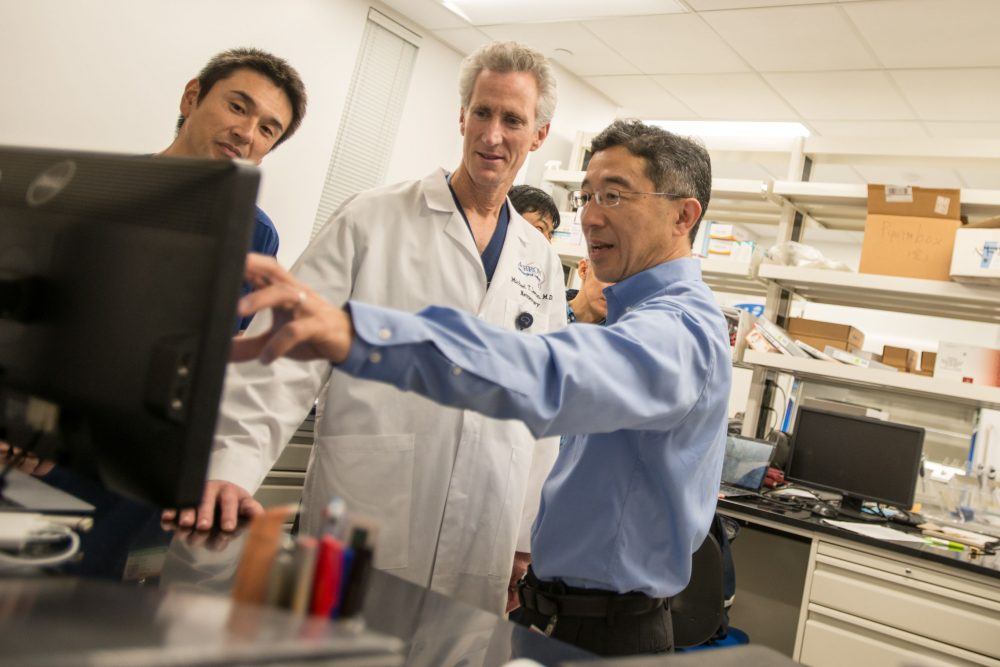

“In terms of mechanism, we found that nicotine promotes aneurysmal rupture through the activation of the α7 nicotinic receptor,” said Dr. Tomoki Hashimoto, who collaborated on the study with Dr. Michael Lawton. “Then, we showed that if we give a drug that blocks this receptor, we can reduce aneurysmal rupture.”

A Drug Therapy: Who Could Benefit?

An aneurysm is a balloon-like bulge in the wall of a weakened blood vessel. It can burst and bleed at any time. When this happens in the brain, it causes a hemorrhagic stroke. An estimated one to five percent of the population harbors an unruptured brain aneurysm.

Many people may not know they have an aneurysm until it becomes a medical emergency. However, doctors are incidentally diagnosing more unruptured brain aneurysms as more people receive brain imaging for other neurological conditions—like migraines and concussions.

Director, Translational Neurovascular Research

Although cigarette smoking has declined in the United States, nearly 38 million American adults smoked cigarettes every day or some days in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That doesn’t include the use of smokeless tobacco products, which also contain nicotine.

“I think it’s easy for doctors to say ‘stop smoking,’ but it’s still quite difficult for some,” Dr. Hashimoto said. “Smoking is very addictive and even if you stop smoking, at least one study has shown risk of aneurysm rupture still remains for an extended time.”

Dr. Hashimoto said the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7*-nAChR) might also serve as a potential therapeutic target for anyone with an unruptured brain aneurysm, whether they use tobacco products or not.

The current options for preventing rupture of a brain aneurysm are surgical clipping or a less-invasive procedure known as endovascular coiling. Both procedures block blood flow into the aneurysm. People who undergo clipping or coiling at high-volume centers like Barrow are likely to have good outcomes.

“But worldwide, these therapies are really technically intensive and expensive,” Dr. Hashimoto said. “So, I think there is a need for pharmacological therapies. Also, some patients may not be the best candidate for surgical treatment.”

Understanding Nicotine’s Role in Aneurysm Rupture

The main goals of the research team at the Barrow Aneurysm and AVM Research Center were to understand how smoking promotes the rupture of brain aneurysms and to look at whether a drug could prevent rupture.

Tobacco contains more than 7,000 different chemicals and is associated with a multitude of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Nicotine is a major biologically active component of tobacco and known to affect nervous system functions.

President and CEO of Barrow

Previous studies have found that nicotine’s interaction with the α7 nicotinic receptor on blood vessel walls promotes inflammation and angiogenesis, or the formation of new blood vessels. Barrow researchers hypothesized that this interaction contributes to the pathophysiology of brain aneurysms, or the functional changes in the body associated with brain aneurysms.

Nicotine can bind to the α7 nicotinic receptor by mimicking a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which plays a role in many bodily functions including muscle movements and memory.

Cells in the nervous system, or neurons, communicate with each other and with muscle and gland cells through neurotransmitters. These chemical messengers latch onto a receiving cell via a receptor specifically designed for them. Acetylcholine receptors are also called nicotinic receptors because of their high affinity for nicotine.

Using preclinical models developed in a Barrow laboratory, the researchers found that nicotine did significantly increase the aneurysm rupture rate. Their models also suggested that this occurs through actions on the α7 nicotinic receptors on smooth muscle cells in the walls of blood vessels and through the promotion of sustained angiogenesis and inflammation.

When they used a substance known to block the α7 nicotinic receptor, it effectively abolished nicotine’s promotion of aneurysm rupture.

“Smoking has long been associated with aneurysm formation and rupture, and our work in the Barrow Aneurysm and AVM Research Center demonstrates how nicotine is a powerful actor in this disease,” Dr. Lawton said. “Our findings emphasize additional dangers in the brain of cigarettes or vaping, beyond what we already see in the lungs.”

Opportunities for Future Research

Dr. Hashimoto said the next step in this line of research is to investigate whether the α7 nicotinic receptor can be targeted in preclinical models without nicotine. In other words, could blocking this receptor prevent brain aneurysm rupture in people who don’t use tobacco products? Then, scientists will need to identify a clinically available drug that can target this pathway.

Vice President, Research

Future studies could also look at whether low doses of nicotine experienced as secondhand smoke can promote brain aneurysm rupture. The doses of nicotine used in this study approximate levels previously reported in heavy smokers.

The models in this study were not specifically designed to detect whether nicotine contributes to the formation of aneurysms, providing another research avenue.

Dr. Hashimoto also emphasized that many more steps must be taken to translate the preclinical findings into human treatments. He and Dr. Lawton, who worked together before coming to Barrow, are creating an archive of human tissues so that they can ask these questions in actual patients and establish a platform for a future clinical trial.

“We are always hopeful,” Dr. Hashimoto said. “By moving to Barrow, I feel like I got a little bit closer because I have a much better platform here.”