Neuropsychological and Phenomenological Correlates of Persons with Dementia and Patients with Memory Complaints but No Dementia

Authors

George P. Prigatano, PhD

Susan Borgaro, PhD

Division of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center

Abstract

Understanding the patient’s subjective experience of their cognitive and emotional functioning may provide important clues for differential diagnoses in neuropsychology. When such information is coupled with findings from the BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions, patients with known dementia can be reliably differentiated from patients with memory complaints but no dementia. It is argued that performance on neuropsychological tests and exploration of the patients’ phenomenological experiences of their symptoms can help make such differential diagnoses.

Key Words: BNI Screen, dementia, memory complaints, phenomenological experience

Patients with dementia, particularly of the Alzheimer’s type, have been studied with a wide variety of neuropsychological measures.[2,4,15,16] So prevalent are neurocognitive and neurobehavioral disorders in such patients that their classification requires objective documentation of specific cognitive deficits to establish the diagnosis of probable dementia.[10]

The current Zeitgeist is to measure neurocognitive correlates of brain disorders and to relate specific cognitive deficits to anatomical abnormalities[12] or disturbances in regional blood flow or metabolism.[7] Still, practicing clinicians must rely on careful clinical observation to detect signs of this illness. In some instances, screening tests such as the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) are helpful.[6] Many patients, however, may “pass” this screening test and still show signs of dementia.[1] Luria[8] was one of the first neuropsychological clinicians to emphasize the importance of patients’ attitudes (i.e., phenomenological experience) about their illness in establishing a differential diagnosis.

Anosognosia, or impaired self-awareness, is common in demented patients, particularly those with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.[9] As the disease progresses, impaired self-awareness typically worsens.[14] However, there is no linear relationship between cognitive deficits as measured by the MMSE and measures of impaired awareness.[17] In clinical practice, demented patients often underestimate their cognitive deficits compared to relatives’ report. This pattern appears to be especially true when patients are asked to rate their level of difficulty with memory. Obtaining patients’ ratings of their level of functioning and comparing them to relatives’ reports during a clinical interview provides important diagnostic information. Understanding the phenomenological state or subjective experience of patients thus enables the clinician to match patients’ perceptions with their actual performance on neuropsychological tests. The combination of these two sets of data may reliably differentiate individuals with dementia from those who complain of memory impairments but who are not demented.

The current study explored this hypothesis. Three predictions were made. (1) Patients with unequivocal dementia would perform at a lower level on the BNI Screen (BNIS) for Higher Cerebral Functioning than patients who complained of memory impairment but lacked neurocognitive signs of dementia. (2) Patients with unequivocal dementia would underreport cognitive difficulties, especially in the area of memory function compared to relatives’ reports. In contrast,(3) patients who complained of memory impairment, but who are not demented, would overestimate their cognitive difficulties compared to relatives’ reports.

Three groups of patients were studied. The first group consisted of individuals with unequivocal dementia who were referred for neuropsychological evaluation to document the severity of their neurocognitive impairments. The second group consisted of age-matched individuals who complained of memory difficulties and who were referred for a neuropsychological evaluation as a part of their evaluation for dementia. Ultimately, this group was deemed to have memory complaints but no clear indication of dementia on neurocognitive examination. The third group consisted of younger patients who also complained of memory difficulties but who performed normally on neuropsychological testing. They were deemed not to have an underlying brain disorder.

All patients were administered the BNIS and interviewed in the presence of a significant other. They were asked to rate their level of difficulty with memory, concentration, word finding, irritability, anxiety, depression, and fatigue. To estimate the patients’ awareness of their difficulties and their attitude toward their neuropsychological and behavioral characteristics, patients’ ratings were compared with ratings made by their significant others. The discrepancy between these two sets of ratings were viewed as a marker of potential disturbances in self-awareness as has been done previously.[13]

Methods

Groups

Seventy-two charts were reviewed to identify patients with neurocognitive findings indicative of probable dementia using the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria of Alzheimer’s disease.[10] Of the 72 charts examined, the clinical neuropsychological examination of 31 individuals (20 males, 11 females; mean age, 69.58 years; standard deviation (SD)=6.69) documented abnormal findings compatible with the diagnosis of probable dementia. Their mean level of education was 13.74 years (SD=3.46).

A second group consisted of agematched individuals who were referred by their physician for a neuropsychological evaluation for memory complaints. Of the 112 charts examined, 21 patients (12 males, 9 females) who were 59 years or older (mean age, 64.68 years; SD=5.76) were found to have memory complaints but no clear signs of dementia on neurocognitive assessment. Their mean level of education was 14.67 years (SD=2.9). This group is referred to as the “older memory complaint” group.

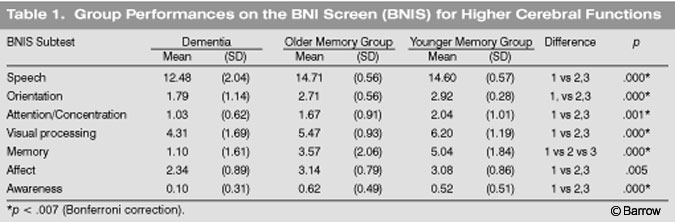

A third group, composed of 25 patients (19 males, 6 females) extracted from the 112 charts of patients referred for memory complaints, were younger than 59 years old (mean age, 47.75 years; SD=6.18; Table 1). These patients also had memory complaints but performed normally on neuropsychological testing. Their mean level of education was 13.52 years (SD=2.2). They are referred to as the “younger memory complaint” group.

There was no significant difference in the ages of the groups with dementia and the older memory complaint group. The younger memory complaint group was significantly younger than the other two groups (p=.00). The mean level of education (p<.388) and the percentages of males and females (p< .405) in the three groups were comparable. For all three groups, the length of their complaints ranged between 12 and 18 months before evaluation.

Patients with a history of major psychiatric disturbance documented on examination were excluded from the study.

Procedures

Before being administered the BNIS, all patients underwent a 30- to 60-minute clinical interview in the presence of at least one relative or significant other familiar with their day-to-day functioning. During their interview, patients were asked to rate verbally the range of difficulty that they had with various dimensions using a scale ranging from 0 to 10. Zero meant no difficulty and 10 meant severe difficulty.

The examiner made clear that the patient understood the instructions. Using this scale, the patient was then asked the following questions: (1) What level of difficulty do you experience in your day-to-day memory for things that are important to you or things that you want to recall? (2) What level of difficulty do you experience in sustaining your concentration? (3) What level of difficulty do you have finding words when expressing yourself to others? (4) What level of difficulty do you have with irritability? (5) What level of difficulty do you have with anxiety? (6) What level of difficulty do you have in keeping from being depressed? (7) What level of difficulty do you have with fatigue?

After patients provided their ratings, the ratings were recorded by the examiner. The relative was then asked to provide his or her ratings of the patient during the clinical interview while the patient was present. In each case, the examiner was a staff clinical neuropsychologist familiar with the BNIS and with how to conduct a clinical interview of patients with known or suspected dementia.

Results

BNIS Total Score and Performance on Memory Subtest

As predicted,patients with dementia performed significantly worse on the BNIS than the two memory complaint groups. Total raw scores were 32.24 (SD=5.19) for the group with dementia, 40.9 (SD=3.78) for the older memory complaint group, and 43.72 (SD= 3.56) for the younger memory complaint group. The scores of the group with dementia were significantly different than those of the other two groups (p=0.000) The BNIS T score (corrected for age) was 19.07 (SD=13.89) for the demented group and 42.90 (SD= 10.84) and 45.88 (SD = 10.05) for the older and younger memory complaint groups, respectively. The difference was significantly reliable [F(2.72)= 41.11, p =0.000].

Both the younger and the older memory complaint groups performed in the average range (mean T score, 50; SD=10). The demented group was more than three SDs below average. The performance of all three groups differed reliably on the memory subtest of the BNIS (Table 1). The demented group clearly performed at a lower level compared to the older memory group. These two groups were also reliably different from the younger memory complaint group. As Table 1 also illustrates, the demented group was reliably different from the memory complaint groups on all other subtests of the BNIS.

Phenomenological Reports of the Three Groups

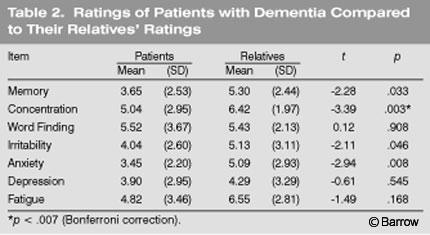

Patients with dementia reported fewer difficulties with memory and concentration than their relatives attributed to them (Table 2). Regarding memory difficulties, patients with dementia rated themselves a mean of 3.65 (SD=2.53) compared to their relatives’ mean rating of 5.30 (SD=2.44,p<.03). In terms of concentration difficulties, patients with dementia rated themselves a mean of 5.04 (SD=2.95) compared to their relatives’ mean rating of 6.42 (SD=1.97;p<.003). The only exception to the pattern of patients reporting fewer difficulties than their relatives attributed to them were the ratings for word-finding difficulties in free speech. Using the Bonferroni correction, only the ratings on concentration were statistically significant (Table 2). The second hypothesis was partially supported.

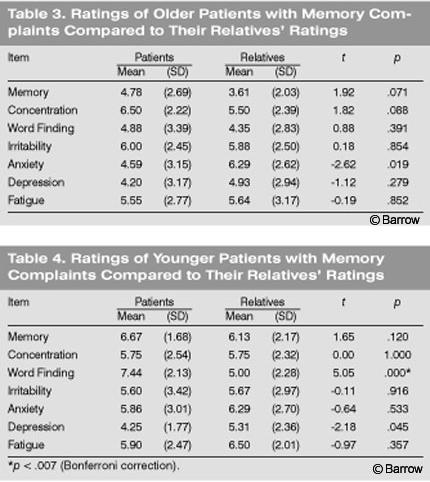

The older patients with memory complaints tended to show the opposite pattern. Their mean ratings of themselves were consistently higher than their relatives’ reports in terms of cognitive complaints (Table 3). Interestingly, they tended to report less anxiety and depression than their relatives attributed to them. None of the mean differences in the older patient group, however, were statistically reliably different using the Bonferroni correction. The younger memory complaint group reported a high level of memory impairment in their day-to-day life. Their relatives typically agreed with the patients’ assessment (Table 4). Strikingly, however, the younger group reported a much higher level of word finding difficulty than their relatives attributed to them. Using the Bonferroni correction, this relationship reached statistical significance (p = .000). Thus, there is partial support for the third hypothesis. Nondemented individuals who complained of memory impairment overstated their problems on certain dimensions compared to their relatives’ reports, but not on all dimensions.

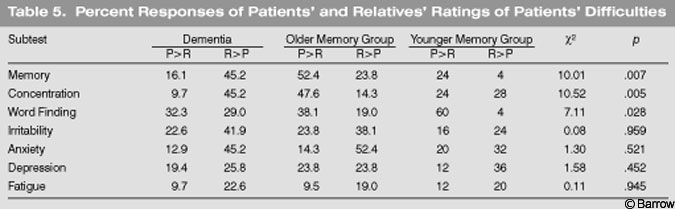

In the demented group, more than 45% of the relatives described patients as having greater memory difficulties than the patients reported (Table 5). The same percentage was found for ratings of concentration difficulties. In contrast, in the older memory complaint group, about half of the time patients reported higher levels of difficulty with memory and concentration than their relatives attributed to them. In contrast,60% of the younger memory complaint group indicated that their word-finding difficulties were worse than their relatives attributed to them. There was an interaction between the age of individuals, their complaints, and the degree to which relatives agreed or disagreed with the level of difficulty patients reported having in different areas of functioning. In general, relatives perceived the memory complaint groups as having more anxiety and depression than the patients’ reported about themselves. This pattern was also present for irritability.

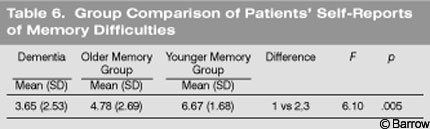

Interestingly, the level of memory difficulty that demented patients reported in their clinical interview was statistically lower than that reported by patients who complained of memory impairment for which no dementia could be identified (Table 6). Performance on neuropsychological testing was the exact opposite. That is, demented patients showed significantly less objective memory function on the BNIS than the other two groups, which were reliably differentiated by this particular measure.

Discussion

Consistent with the literature, the present study documented that patients with dementia performed worse on the BNIS than individuals who complain of memory impairment but who have no objective signs of dementia. Thus the first hypothesis of this study was clearly supported.

Analysis of patients’ ratings of their functioning on various dimensions and comparisons of their ratings to relatives’ reports reaffirms that demented patients tend to underestimate their cognitive difficulties compared to their relatives’ perceptions. In the present study, demented patients underestimated problems with memory and concentration. However, the difference was statistically reliable using the Bonferroni correction only for the dimension of concentration. In general, however, patients tended to underestimate their difficulties compared to their relatives’ ratings (Table 5). Almost 50% of the time, demented patients reported fewer difficulties with memory and concentration than their relatives attributed to them. This pattern did not occur in the memory complaint groups. Thus, the second hypothesis that patients with unequivocal dementia would underreport cognitive difficulties was partially supported.

The third hypothesis that patients who complained of memory impairment for which objective evidence was lacking would overestimate their cognitive difficulties was clearly supported. In both the older and younger memory complaint groups, patients tended to overstate their problem compared to their relatives’ ratings of their level of function (Table 5). However, the difference in complaints between the older and younger memory group is interesting. Somewhat surprisingly, the younger memory complaint group reported a much higher level of word-finding difficulties than their relatives attributed to them. In the older group, the pattern seemed to be more pronounced for memory and concentration complaints.

Patients with “true dementia” reported fewer memory difficulties in their daily functioning than both the older and younger memory complaint groups. This underreporting appears to reflect anosognosia in the group with dementia. Seltzer et al.[13] specifically noted that patients with dementia of the Alzheimer’s type underreport memory impairments and this poses a great burden for caregivers.

Zanetti et al.[17] suggested that anosognosia is nonlinearly related to the cognitive status of patients. When MMSE scores are equal to or higher than 24, “insight was uniformly high” (p 100). When MMSE scores were less than or equal to 12, they were “uniformly low.” The linear decrease occurred between scores 23 and 13. This same type of analysis should be attempted with BNIS Total scores and scores on selected subtests to further clarify the role of various cognitive and affective disturbances in anosognosia during dementing conditions.

Derouesne et al.[5] studied impaired awareness in patients with Alzheimer’s disease who had mild cognitive impairments. Patients were aware of their difficulties but “failed to appraise their severity and their consequences in everyday life” (p 1019). This experience is common in clinical practice and reflects our experience while conducting the study. Patients with dementia reported memory difficulties but at a lower level of severity than their relatives attributed to them. They also seemed to have difficulties understanding the impact of their impairments on their daily life. This lack of awareness may be especially problematic when patients need to restrict their driving. Patients with dementia often drive beyond the time that caregivers express their concern about the patients doing so.[3] A major challenge in working with these patients is to “enter their phenomenological field”[11] and help them to experience concern about such safety issues, particularly before their anosognosia becomes severe.

Neuropsychological assessments of patients with memory complaints should document their actual level of functioning. Clinicians should understand what patients are experiencing in terms of their memory impairments. The combination of these two sources of information should help clinicians guide patients and families to make better choices and to improve management of their loved one.

References

- Albert MS, Moss MB, Tanzi R, et al: Preclinical prediction of AD using neuropsychological tests. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 7:631-639, 2001

- Butters N, Delis DC, Lucas JA: Clinical assessment of memory disorders in amnesia and dementia. Ann Rev Psychol 46:493-523, 1995

- Cotrell V, Wild K: Longitudinal study of self-imposed driving restrictions and deficit awareness in patients with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 13:151-156, 1999

- Cummings JL, Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology: Assessment: Neuropsychological testing of adults. Considerations for neurologists. Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 47:592-599, 1996

- Derouesne C, Thibault S, Lagha-Pierucci S, et al: Decreased awareness of cognitive deficits in patients with mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int J Geriat Psychiatry 14:1019-1030, 1999

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: “Minimental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 12:189-198, 1975

- Hoffman JM, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Hanson M, et al: FDG PET imaging in patients with pathologically verified dementia. J Nucl Med 41:1920-1928, 2000

- Luria AR: Higher Cortical Functions in Man. New York: Basic Books, 1966

- McGlynn SM, Kaszniak AW: Unawareness of deficits in dementia and schizophrenia, in Prigatano GP, Schacter DL (eds): Awareness of Deficit After Brain Injury: Clinical and Theoretical Issues. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991, pp 84-110

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al: Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 34:939-944, 1984

- Prigatano GP: Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999

- Salmon E: Functional brain imaging applications to differential diagnosis in the dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 15:439-444, 2002

- Seltzer B, Vasterling JJ, Yoder JA, et al: Awareness of deficit in Alzheimer’s disease: Relation to caregiver burden. Gerontologist 37:20-24, 1997

- Starkstein SE, Sabe L, Chemerinski E, et al: Two domains of anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 61:485-490, 1996

- Weintraub S: Mental state assessment of young and elderly adults in behavioral neurology, in Mesulam M-M (ed): Principles of Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000, pp 71-123

- Welsh-Bohmer KA, Morgenlander JC: Determining the cause of memory loss in the elderly. From in-office screening to neuropsychological referral. Postgrad Med 106:99-118, 1999

- Zanetti O, Vallotti B, Frisoni GB, et al: Insight in dementia: When does it occur? Evidence for a nonlinear relationship between insight and cognitive status. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 54:100-106, 1999