Empty Sella Syndrome

At a Glance

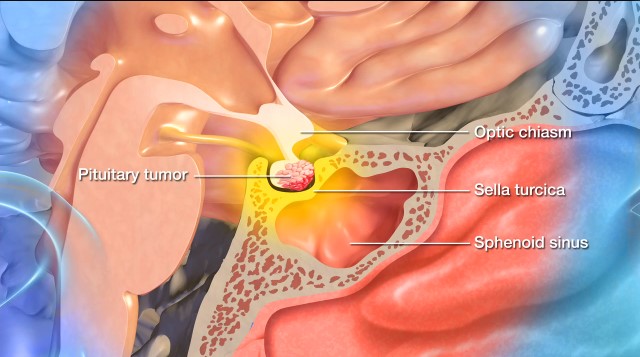

- Empty Sella Syndrome occurs when the pituitary gland becomes shrunken or flattened, making the sella turcica (the bony structure that surrounds and protects the gland) appear empty.

- Although it may not cause symptoms, in some cases, it can lead to hormone imbalances or vision problems.

- The condition is usually discovered incidentally through medical imaging performed for other reasons.

- Treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and may involve hormone replacement or regular monitoring.

Overview

Empty sella syndrome (ESS) is a rare condition in which the sella turcica—a bony structure within the skull base surrounding and protecting the pituitary gland—appears partially or completely empty on imaging scans. Despite the name, the sella turcica is not truly empty, as the pituitary gland is still present, but it may be compressed or flattened, which allows clear and colorless cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to fill the space.

Empty sella syndrome is often discovered incidentally—for example, after brain imaging is done for other unrelated reasons.

Did you know?

The sella turcia is a saddle-shaped depression within the base of the skull that contains the pituitary gland. Its name means “Turkish saddle” in Latin.

What causes empty sella syndrome?

There are two types of empty sella syndrome:

- Primary empty sella syndrome (ESS): This is the more common subtype of ESS and is thought to occur when CSF partially or completely fills the sella turcica due to a developmental defect above the pituitary gland. This, in turn, pushes the pituitary gland against the walls of the sella turcica, causing it to flatten.

- Secondary empty sella syndrome (ESS): This subtype of ESS results from an identifiable problem, such as damage to the pituitary gland caused by trauma, brain surgery, radiation, increased intracranial pressure or inflammation, as well as other conditions affecting the pituitary gland, like a pituitary tumor. In secondary ESS, the pituitary gland regresses within the sella turcica cavity after an injury or surgery.

Empty Sella Syndrome Symptoms

Many people with ESS—especially primary ESS—may not experience symptoms. When symptoms do occur, they are typically related to hormonal imbalances, increased intracranial pressure from CSF, or pituitary dysfunction.

If you or someone you know have ESS, you may experience any of the following:

- Headaches: One of the most common symptoms of ESS, very likely due to the increased pressure from CSF.

- Vision problems: Pressure on the optic nerves from CSF can cause blurred vision, double vision, or a loss in your visual field.

- Weight gain: Weight gain can occur if the pituitary gland affects the release of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) due to ESS. Lower thyroid hormone levels can slow metabolism, leading to weight gain.

- Hormonal imbalances: These symptoms can include thyroid problems, irregular periods, or even infertility. These changes in or deficiencies of hormones can then lead to conditions like adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, or growth hormone deficiency.

- Fatigue: Hormonal fluctuations can cause fatigue from low thyroid, growth hormone, or imbalanced adrenal hormones.

- Low libido: In this instance, a decrease in libido is directly related to a deficiency in your testosterone levels.

- Intolerance to stress and infection: When the pituitary gland is affected—particularly from secondary ESS—low cortisol levels due to adrenal insufficiency can affect the body’s ability to cope with stress and fight infections.

Please note that the presence of one or more of these symptoms doesn’t mean you have ESS. A thorough evaluation by a healthcare professional is required to make an accurate diagnosis.

Empty Sella Syndrome Diagnosis

To diagnose empty sella syndrome (ESS), a physical and neurological examination, paired with imaging studies, is often all that’s needed:

- Physical and neurological exam: First, your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms, overall health, and family history. Next, they’ll complete a physical and neurological examination to assess your overall functioning, including your reflexes, coordination, strength, and sensation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): An MRI is the gold standard for diagnosing ESS because it provides detailed images of organs and their surrounding tissues and structures, like the sella turcica. It can determine if increased CSF pressure is flattening the pituitary gland. An MRI can also help distinguish between primary and secondary ESS.

- Computed Tomography (CT): A CT scan relies on X-rays to create detailed images of your brain and pituitary gland—including the sella turcica—and can be used if you cannot undergo an MRI. Although less detailed than an MRI, a CT scan can still show if you have ESS.

- Blood test: Because ESS can affect the pituitary gland’s ability to regulate hormones, a pituitary hormone panel is often done to assess for pituitary hormone deficiencies.

- Lumbar puncture: Also known as a spinal tap, a lumbar puncture may be done when additional information is needed to help clarify a diagnosis.

- Eye exam: If ESS leads to compression of your optic nerves, an ophthalmologic exam or visual field test may be done to examine your retina and check for vision loss.

Empty Sella Syndrome Treatment

ESS is not life-threatening; you may not even need treatment if your pituitary gland produces a standard range of hormone levels. Your doctor will tailor your treatment to your symptoms and hormonal function.

Primary ESS doesn’t require any treatment unless you’re experiencing symptoms—and in this case, the following treatments could be used to manage your symptoms:

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT): When primary ESS causes pituitary hormone deficiencies, like low thyroid, adrenal, or growth hormone levels, HRT may be used. While your treatment will be personalized depending on which of your hormones are affected, HRT can involve taking a thyroid hormone if your thyroid hormone levels are low, estrogen or progesterone in women, or testosterone in men.

- Headache management: If you experience an increase in headaches due to growing pressure from CSF, pain relievers or medications for migraines can be prescribed. Seeing a Neurologist may help, as they can perform procedures to relieve the raised intracranial pressure. Your doctor might also recommend lifestyle changes to induce weight loss.

- Management of increased intracranial pressure: In primary ESS cases linked to increased intracranial pressure, diuretics can be used to reduce CSF together with medication/s to manage hypertension and weight loss.

Since secondary ESS is generally the result of damage to the pituitary gland, treatment will often focus on the underlying cause. For example, if your secondary ESS is caused by a brain or pituitary tumor, managing the tumor through surgery, minimally invasive surgical techniques, or radiation therapy will be critical.

Other treatment options for secondary ESS can include:

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT): When there are demonstrable hormone deficiencies, hormone replacement therapy is used to restore balance. While your treatment will be personalized depending on which of your hormones are affected, HRT can involve taking a thyroid hormone if your TSH is low, estrogen or progesterone in women, or testosterone in men.

In both subtypes of ESS, regular follow-ups with an endocrinologist may be necessary to monitor your hormone levels and adjust your treatment as needed.

In sporadic cases where a CSF leak or severe vision problems occur due to ESS, other surgical interventions may be necessary. These can include:

- CSF leak repair surgery: Surgery is often needed to repair a CSF leak and to prevent infection. The neurosurgeon repairs the sella turcica through the nasal passages and the sphenoid sinus using a small surgical instrument and an endoscope.

- Decompression surgery: In the event ESS produces severe pressure on the optic nerves and triggers vision loss, a surgical decompression using the transsphenoidal approach may also be performed.

Overall, most cases of ESS are manageable, and many people live normal lives without needing surgery or developing complications.

Common Questions

How common is empty sella syndrome?

Empty sella syndrome (ESS) is rare, although its exact prevalence is not well established.

Who gets empty sella syndrome?

Although it can occur at any age, doctors most often diagnose ESS in middle-aged adults. It’s more commonly seen in women versus men, particularly those who have high blood pressure or are overweight.

What is the prognosis for someone with empty sella syndrome?

The prognosis is generally good. Many people with primary ESS live normal, healthy lives without requiring treatment because they don’t often experience symptoms or complications.

The overall prognosis for secondary ESS will depend on the underlying cause. If surgery, radiation therapy, or trauma has significantly damaged your pituitary gland, your hormonal deficiencies may be permanent, requiring long-term endocrine management, such as lifelong monitoring and hormone replacement therapy.

Can empty sella syndrome be prevented?

While there is no known way to prevent empty sella syndrome (ESS), specific steps may help lower the risk of secondary ESS or general complications from ESS:

- Managing your weight and blood pressure: Since ESS is more common in those who have high blood pressure or are overweight, maintaining a healthy lifestyle—incorporating daily movement and exercise, eating a variety of whole foods and fewer unprocessed foods, improving the quality of sleep, and practicing stress management—can reduce your risk.

- Preventing head trauma: Because head trauma can contribute to pituitary damage, wearing protective gear during high-risk activities will help you reduce the risk of damage to your brain and pituitary gland

- Monitoring pituitary health: If you have a history of pituitary disorders, regular check-ups with an endocrinologist are essential to detect changes to your condition as soon as possible.

- Addressing intracranial pressure: If you have idiopathic intracranial hypertension, a neurologist may be able to help you plan for treatment to prevent complications.