Pituicytoma

At a Glance

- A pituicytoma is an extremely rare, noncancerous brain tumor that forms at the base of the brain in the pituitary gland, its stalk, or the hypothalamus.

- Because they are so rare—doctors have diagnosed fewer than 200 cases worldwide—the exact cause of pituicytoma is unknown.

- Symptoms of a pituicytoma can include visual disturbances, headaches, fatigue, and changes to hormone levels that can affect your mood or behavior.

- Surgery is the primary treatment for pituicytoma and is often curative upon complete removal of the tumor.

Overview

A pituicytoma is a rare and noncancerous brain tumor that arises from pituicytes. These are specialized glial cells found at the base of the brain in the posterior pituitary gland, in the stalk of the pituitary gland, or, occasionally, in the hypothalamic region of the brain.

Pituicytomas are classified as World Health Organization (WHO) Grade 1 gliomas, meaning they’re tumors that start in the glial cells, grow slowly, and are typically not aggressive or cancerous. They’re considered a single tumor type, without any subtypes, because of their consistently uniform characteristics.

While pituicytomas are often benign and slow-growing, their size and location can affect pituitary and hypothalamic function.

Did you know?

CM Scothorne, a notable British anatomist and educator, described the first known case of pituicytoma in 1955. To this day, pituicytomas remain very rare.

What causes pituicytoma?

The exact cause of pituicytoma tumors is unknown. Scientists think they originate from pituicytes, which support and regulate hormone release from the pituitary gland.

Sporadic changes or cell mutations are the likely cause, rather than genetic syndromes or environmental factors. However, the rarity of the condition limits the amount of research available.

Pituicytoma Symptoms

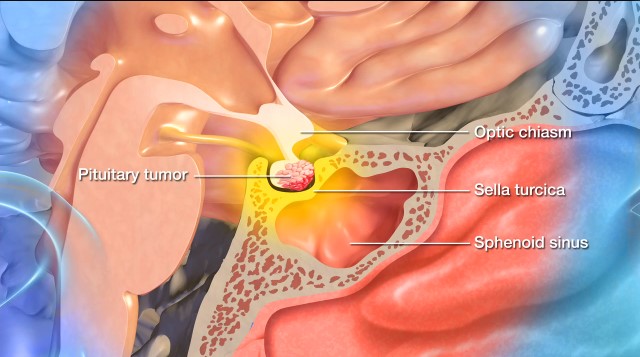

The symptoms of a pituicytoma tend to develop slowly over time. The benign tumor’s pressure on nearby structures in the brain, like the optic chiasm, pituitary gland, and hypothalamus, causes symptoms. Most often, a pituicytoma presents with pituitary gland and optic nerve dysfunction.

If you or someone you know has a pituicytoma, you may experience a combination of the following symptoms:

- Visual disturbances: Compression of nearby nerves can cause blurred vision, loss of peripheral (side) vision (bitemporal hemianopsia), and double vision (diplopia).

- Fatigue or low energy: Pituicytomas can cause hormone reduction and overproduction, leading to fatigue from a lack of the right hormones for energy regulation. Persistent pressure from these benign tumors can also lead to fatigue and reduced physical or mental energy.

- Headaches: When a tumor compresses pituitary tissue, it leads to changes in intracranial pressure. These headaches are typically located on the forehead or behind the eyes but can vary in location and intensity.

- Irregular menstruation or infertility in women: Menstrual irregularities or cessation of your menstrual cycle can be indicative of a tumor affecting your pituitary gland.

- Decreased libido or erectile dysfunction in men: A decrease in sexual drive, as well as an onset of erectile dysfunction, can be indicative of a pituicytoma due to a lack of testosterone.

- Unexplained weight gain or loss: Sudden or unexpected weight gain or loss can occur due to a tumor causing pituitary gland malfunction.

- Arginine-vasopressin deficiency: If the posterior pituitary gland is involved, this condition, formerly known as diabetes insipidus, can occur. This is when the body cannot properly regulate water balance, which leads to excessive thirst and urination.

- Nausea and vomiting: Increased intracranial pressure from a pituicytoma can trigger nausea and vomiting.

- Behavioral changes: If a pituicytoma compromises the function of the hypothalamus, behavioral changes like irritability or depression can occur.

Because most of these symptoms overlap with symptoms of other tumors located in the sella turcica, a bony structure that houses the pituitary gland, imaging and biopsy are often needed to confirm a pituicytoma diagnosis.

Pituicytoma Diagnosis

Doctors use the following exams, tests, and imaging studies to diagnose a pituicytoma:

- Physical exam: First, your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms, overall health, and family history. Next, they’ll examine your visual fields to assess for any visual disturbances caused by the pituicytoma.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Imaging studies are crucial in visualizing the brain and identifying abnormalities, and an MRI is the gold standard for assessing pituitary tumors. An MRI provides detailed images of the pituitary gland and its surrounding structures. However, it cannot definitively distinguish a pituicytoma from a meningioma, pituitary adenoma, or other tumors in the same area.

- Blood Testing: When it comes to pituitary tumors, specific blood tests are needed to assess your pituitary function and measure hormone production that may or may not be affected by the pituicytoma.

- Biopsy: While imaging and hormone testing can raise suspicion of a pituicytoma, a definitive diagnosis requires a tissue analysis after surgical removal. After the operation, your neurosurgeon will send a sample of the tumor to a pathologist, who will analyze it under a microscope to see if the cells match those associated with a pituicytoma.

- Ophthalmologic exam: This eye exam can be a valuable part of a pituicytoma diagnosis, since a tumor that compresses the optic chiasm can cause a kind of vision loss called bitemporal hemianopsia. This affects the peripheral side vision in both eyes.

Pituicytoma Treatment

Surgery is the primary and most effective treatment for pituicytoma. Because pituicytomas are usually benign, slow-growing, and well-defined, the goal of surgery is to completely remove the tumor, offering the best chance of a cure.

Surgical Treatments

In pituicytoma surgery, the goal is a complete resection, or total removal of the tumor. That said, the tumor’s proximity to critical structures like the optic nerves or hypothalamus may prohibit a pituicytoma’s complete removal.

The choice of surgical approach depends on the tumor’s size and location and may include:

- Transsphenoidal surgery: The most common surgical approach for a pituitary tumor is transsphenoidal surgery. This is when a neurosurgeon reaches and removes the tumor through the nasal passages and the sphenoid sinus using a small surgical instrument and an endoscope. Transsphenoidal surgery works best on small to medium-sized pituitary tumors confined to the sella turcica—the bony compartment of the pituitary gland—and leaves no scar. It also minimizes the risk of complications and offers a faster recovery.

- Craniotomy: Larger, more complex tumors may require the surgical opening of your skull, known as a craniotomy. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon will make an incision in the scalp, remove a portion of the skull, and access the brain to remove the tumor, all while using intraoperative imaging and highly specialized tools to visualize and safely remove the tumor. This procedure is more invasive than transsphenoidal surgery and requires a longer recovery time. Fortunately, neurosurgeons rarely perform this procedure for pituitary tumors nowadays.

Tumors rarely reappear after complete removal. However, in some cases, only a partial removal can be done to avoid unwanted neurological damage.

Nonsurgical Treatments

Nonsurgical treatments for pituicytoma are limited but can be used in specific situations. These include:

- Radiation therapy: This nonsurgical treatment is only used if surgery is incomplete and the pituicytoma grows back or continues to grow. However, this approach is uncommon, as pituicytomas are not very radiosensitive. Radiation therapy uses precisely aimed beams of radiation to destroy tumors in the body—while it doesn’t remove the tumor, radiation therapy damages the DNA of the tumor cells, which then lose their ability to reproduce and eventually die.

- Radiosurgery: This treatment relies on a radiation delivery system to focus on the site of the pituitary tumor and minimize radiation dose to the brain. The two most common forms of radiosurgery are:

- Gamma Knife radiosurgery: This technique destroys abnormal tissue using precise and focused radiation beams and is only lethal to cells within the immediate vicinity. It’s an outpatient procedure that doesn’t involve incisions and requires brief sedation under a general anesthetic.

- CyberKnife radiosurgery: This technique uses targeted energy beams to destroy tumor tissue while sparing healthy tissue. It uses image-guided robotics to deliver surgically precise radiation to help destroy pituitary tumors. CyberKnife is also an outpatient procedure and does not require general anesthesia.

- Hormone therapy: If you’ve developed hormone deficiencies due to pressure from the pituicytoma or have experienced surgical damage, you may need lifelong hormone replacement therapy, such as thyroid hormone and glucocorticoids.

- Observation and monitoring: If your neurosurgeon is unable to remove the entire tumor or if surgery is too risky, they may recommend careful observation with regular MRIs. This is especially true for small tumors that aren’t causing symptoms. This “watch-and-wait” approach allows doctors to monitor for any signs of tumor growth or worsening symptoms.

Overall, nonsurgical treatments serve mainly as supportive or secondary options when surgery alone isn’t curative or feasible. Supportive care can also be essential to treatment, such as medications to manage pain, seizures, and swelling in the brain and access to physical and occupational therapy as needed.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s renowned Pituitary Center, we treat people with pituitary tumors and disorders in one robust location. And because our doctors and nurses treat more people with pituitary disorders than any other team in the Southwest U.S., you can rest assured that you’ll be in very experienced hands.

Common Questions

How common is a pituicytoma?

Pituicytomas are exceptionally rare; fewer than 200 cases have been reported in medical literature worldwide.

Because they are so rare, pituicytomas are not tracked separately in the United States; instead, researchers frequently group them under “rare tumors” or other brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors. Experts estimate that fewer than 1 in 10 million people per year are diagnosed with pituicytoma in the U.S., and they make up less than one-half of a percent of all tumors found in the sellar and suprasellar region.

Who gets a pituicytoma?

Pituicytomas are most commonly diagnosed in adults between 30 and 60, although doctors have documented cases outside this age range. They occur in males and females equally.

What is the prognosis for someone with a pituicytoma?

The prognosis for someone with a pituicytoma is generally favorable, especially when a neurosurgeon obliterates the tumor through surgery. They are benign, slow-growing, noninvasive, and rarely spread or become aggressive.

With total surgical resection or removal, long-term outcomes are often excellent, with a low risk of recurrence. However, complete pituicytoma removal can be challenging due to its location near critical structures. In cases where only a partial resection is feasible, the pituicytoma can slowly regrow over time, and regular monitoring with MRI scans is required.

With proper surgical management and follow-up care, most patients with pituicytoma have a good quality of life and a favorable long-term outlook.

Can pituicytomas be prevented?

You cannot prevent a pituicytoma. The exact cause of these tumors remains unknown, and researchers have not linked them to any known genetic mutations, environmental exposures, or lifestyle factors. They appear sporadically, likely due to random mutations in specialized glial cells in the posterior pituitary gland.

Although they can’t be prevented, early detection and treatment remain essential. Prompt evaluation of symptoms—especially vision changes, persistent headaches, or hormone-related issues—can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Resources

American Journal of Neuroradiology