Subependymoma

Overview

Subependymomas are rare brain tumors that develop along the walls of ventricles, or fluid-filled spaces in the brain.

Due to their slow growth and typically noncancerous or benign nature, many people with subependymomas may not realize they have one, especially when the tumor is small and asymptomatic. Doctors find most subependymomas by chance. When symptoms do occur, they’re often the result of the tumor pressuring surrounding brain structures; particularly if it obstructs cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), leading to fluid buildup in the brain known as hydrocephalus.

Subependymomas are classified as Grade 1 tumors, meaning they have a very low risk of becoming cancerous or malignant and are highly unlikely to spread to other parts of the brain or body.

What’s the difference between an ependymoma and a subependymoma?

Subependymomas are an ependymoma subtype—they’re grade 1 ependymomas that are considered a more benign form of the condition with a better prognosis.

What causes subependymoma?

Subependymomas originate from subependymal glial cells that line the brain’s ventricular walls. For reasons not yet fully understood, these subependymal glial cells can grow abnormally, producing this slow-growing tumor.

Researchers think they arise from random mutations in glial cells lining the brain’s ventricles. These mutations are sporadic, with no established genetic or lifestyle-related risk factors.

Subependymoma Symptoms

Most subependymomas are asymptomatic—meaning they don’t cause symptoms—especially when small. Incidental discovery, when doctors uncover a new problem when looking for something entirely different, is common with ependymomas. When symptoms are present, they’re usually related to the subependymoma’s effect on the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

If you have a subependymoma, you might experience any of the following symptoms:

- Headaches: A subependymoma can block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in your brain, leading to increased intracranial pressure or even hydrocephalus.As a result, the headaches you may experience are often persistent, can worsen in the morning, or become more severe with physical activity.

- Nausea and vomiting: Increased intracranial pressure from the size of your subependymoma or fluid buildup can also trigger nausea and vomiting, especially in the morning.These symptoms often occur alongside headaches.

- Hydrocephalus-related symptoms: In cases where the subependymoma causes significant blockage of CSF, hydrocephalus can develop. Characterized by excess CSF in the brain, this condition can lead to a host of symptoms like severe headaches, vomiting, drowsiness, and changes in balance or the way you walk.

- Vision problems: Increasing intracranial pressure or pressure on the optic pathways can lead to visual disturbances, including blurry or double vision. Swelling of the optic nerve, known as papilledema, may also occur.

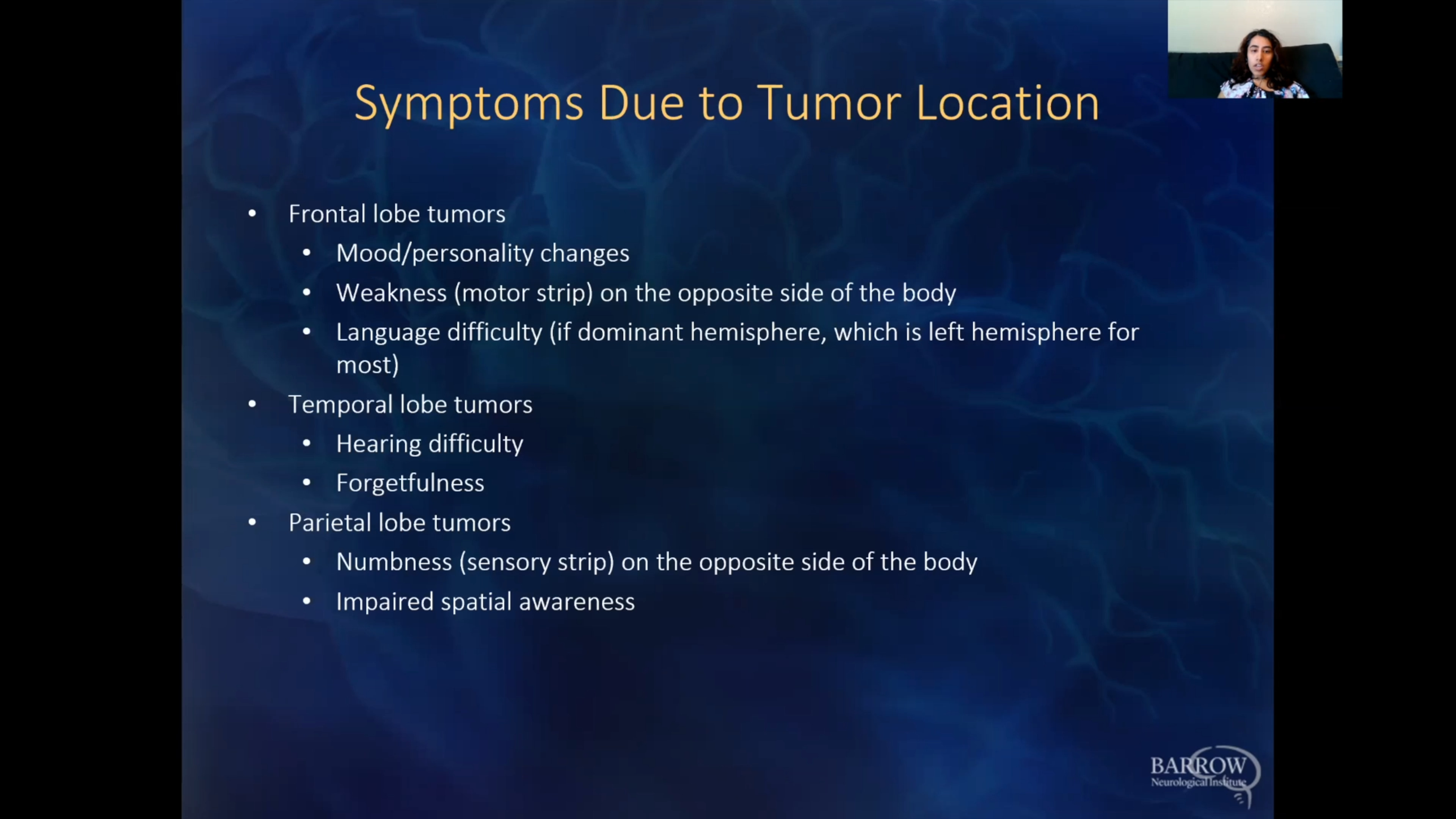

- Balance and coordination issues: A subependymoma in the fourth ventricle of your brain can press on nearby structures responsible for balance and coordination and lead to difficulty walking, clumsiness, or general instability.

- Cognitive and behavioral changes: Increased intracranial pressure can lead to cognitive issues, like confusion, changes in behavior, or problems with memory. Some people may also experience irritability or mood swings.

These symptoms can overlap with those caused by other conditions, so it’s essential to consult a healthcare professional if you’re experiencing one or more of them. Even in the case of slow-growing subependymomas, early detection can improve outcomes.

Subependymoma Diagnosis

Physicians diagnose subependymomas through exams, imaging studies, and sometimes tissue sampling. Because they are generally asymptomatic, they’re often found during imaging for other medical reasons.

The most common diagnostic tests for subependymoma include:

- Physical and neurological exam: First, your provider will begin by reviewing your symptoms and medical history. Next, a neurological examination will check your vision, coordination, reflexes, strength, and other functions controlled by the brain or spinal cord.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The most common diagnostic test for a subependymoma, an MRI uses strong magnets and radio waves to provide detailed brain and spinal cord images to determine a tumor’s location, size, and characteristics. Subependymomas typically appear as well-defined, non-invasive masses on an MRI scan.

- Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans rely on X-rays to create detailed cross-sectional images of the brain, helping to detect tumors while evaluating their size and location. In some cases, a CT scan may show subependymomas, especially if there’s evidence of hydrocephalus in the brain.

- Biopsy: In most cases, a biopsy of a subependymoma is not necessary. However, if your tumor has atypical features that make your diagnosis uncertain or if it’s causing symptoms that make surgical removal necessary, your care team may recommend one. During a biopsy, a small sample is removed from the tumor and sent to a pathology laboratory for analysis. There, pathologists examine the tissue under a microscope to determine the type of cells present and other important characteristics that guide treatment decisions. For tumors in the brain, a biopsy is typically done surgically or through stereotactic biopsy.

- Lumbar puncture: Also known as a spinal tap, a lumbar puncture involves a needle inserted into the lower back to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for testing. Lumbar punctures are generally not a diagnostic tool for subependymomas, but they can help rule out an infection or another condition that may be causing similar symptoms.

Overall, an MRI is the gold standard for diagnosing subependymomas, and most cases are diagnosed based on imaging studies alone. Additional tests are usually reserved for exceptional cases requiring supplementary confirmation.

Subependymoma Treatment

Surgical Treatments

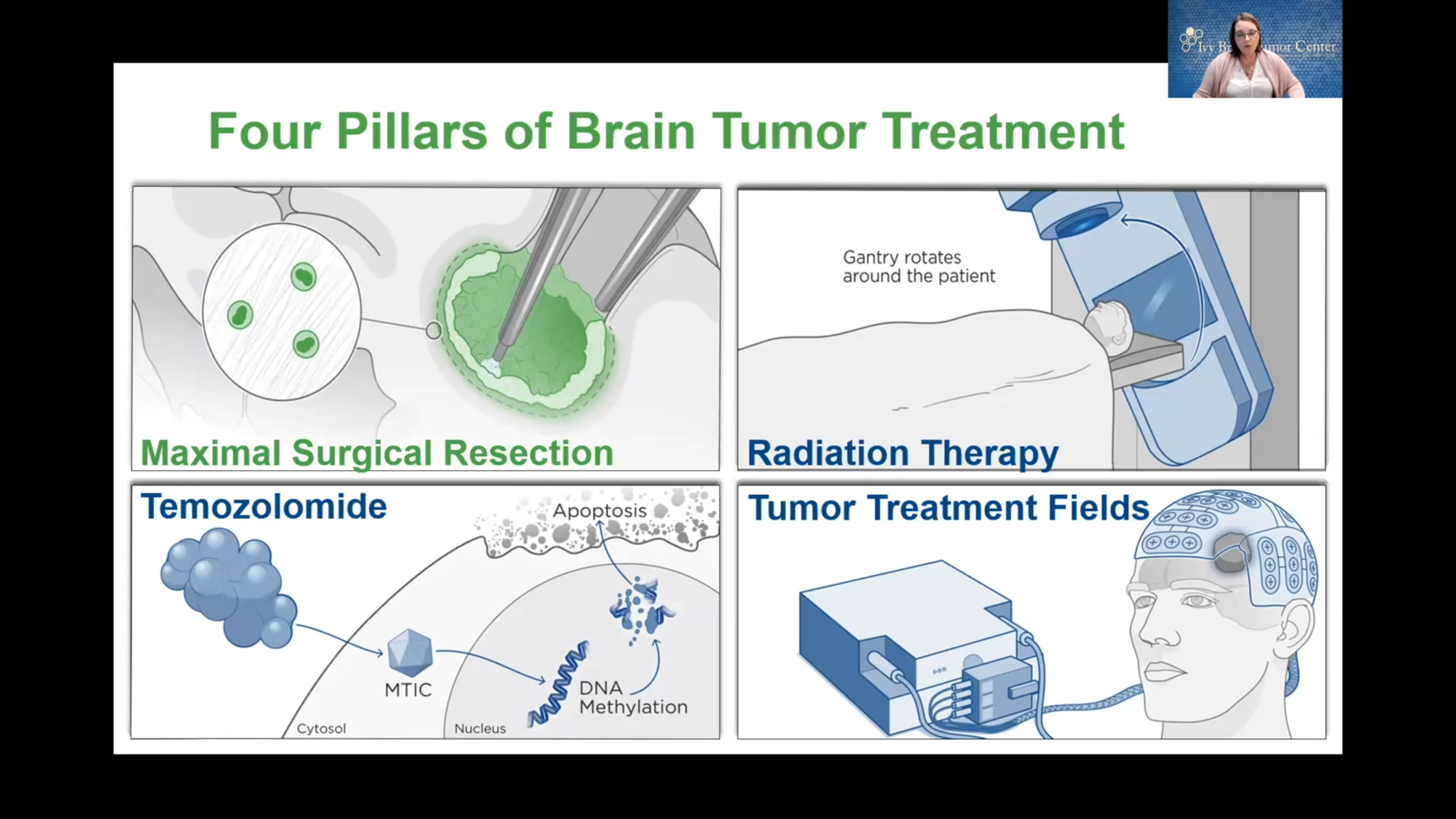

Because subependymomas are so well-defined, the goal of surgery is total removal, known as complete resection. Complete resection is often attainable—especially when the subependymoma is located in an accessible part of the brain or, rarely, the spinal cord.

Two of the common surgical treatments for subependymomas are:

- Craniotomy: A craniotomy is the most common surgery for brain tumors, including subependymomas. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon will make an incision in the scalp, remove a portion of the skull, and access the brain to remove the tumor, all while using intraoperative imaging and highly specialized tools to visualize and safely remove the abnormal tissue.

- Endoscopic surgery: Endoscopic surgery may be used for some subependymomas. A neurosurgeon makes a small incision in the skull, and a neuroendoscope, or a small, flexible tube with a camera and surgical tools, is inserted into the brain to remove the tumor with minimal disruption to surrounding brain tissue. Endoscopic surgery is minimally invasive, meaning smaller incisions and shorter recovery times.

In cases where a subependymoma has caused hydrocephalus, a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt or endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) may be done to relieve fluid buildup and pressure in the brain.

- Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt: Occasionally, subependymomas can block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), leading to hydrocephalus. A VP shunt can drain excess fluid from the brain to the abdomen to relieve pressure and symptoms like headaches, nausea, and vision problems.

- Endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV): This minimally invasive procedure creates a small hole in the brain’s third ventricle, which allows CSF to bypass the blockage caused by the subependymoma and drain normally. An ETV is generally preferred over a VP shunt as it avoids the need for a permanent shunt.

If part of the subependymoma remains after surgery, your doctor may recommend additional nonsurgical treatments to target any remaining cancerous cells. Periodic follow-up imaging may be needed to ensure the subependymoma does not recur.

Nonsurgical Treatments

The primary nonsurgical approach for most subependymomas remains careful observation, as they’re usually benign and slow-growing. As such, nonsurgical treatments are generally supportive and focus on symptom relief or monitoring.

Additional nonsurgical treatments include:

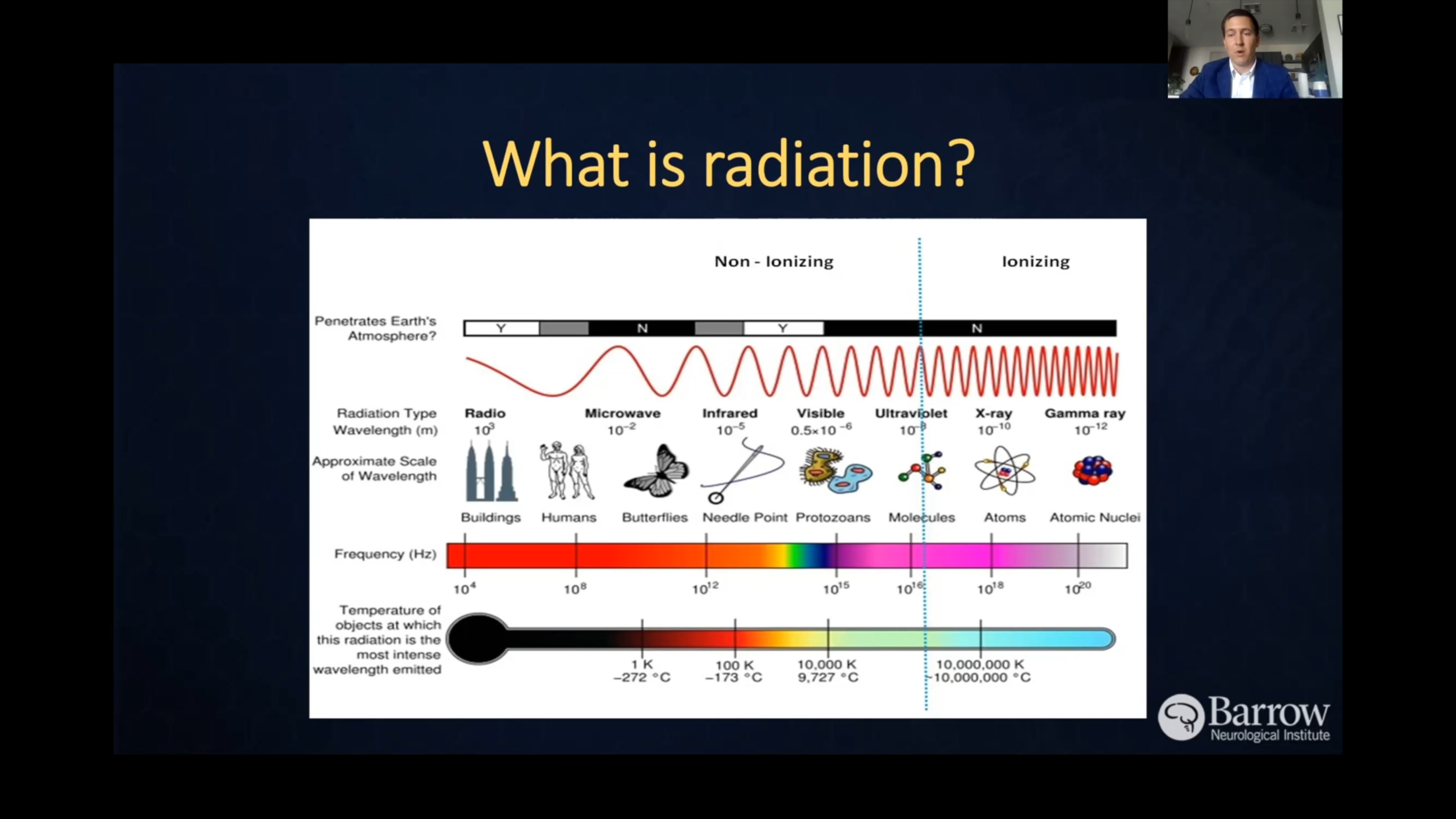

- Radiation Therapy: Although rarely needed, radiation therapy may be considered if your subependymoma is symptomatic but not fully removable due to its location. Radiation therapy uses precisely aimed beams of radiation to destroy tumors. While it doesn’t remove the tumor, radiation therapy damages the DNA of the tumor cells, which then lose their ability to reproduce and eventually die.

- Pain management: Over-the-counter medications like acetaminophen or ibuprofen can help relieve headaches due to intracranial pressure.

- Anti-nausea medications: In cases where nausea is problematic, anti-nausea medications may help to relieve discomfort from added intracranial pressure.

- Hydrocephalus medications: If your subependymoma causes symptoms related to hydrocephalus, diuretics may temporarily reduce intracranial pressure. Over the long term, surgery may become necessary to relieve fluid buildup. Corticosteroids can also be used in the short term to reduce inflammation and brain swelling.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s world-class Brain and Spine Tumor Program, we treat people with complex tumors like subependymomas in one robust, full-service location. Our sophisticated multidisciplinary team—neurosurgeons, head and neck surgeons, neuro-oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, to name a few—can offer you the latest treatments for head and neck cancers.

We also give our patients access to various neuro-rehabilitation specialists to maximize independence. Neuro-rehabilitation can include physical therapy to help you regain strength and balance, speech therapy to support speaking, expressing thoughts, or swallowing, and occupational therapy to aid you in managing daily activities like bathing, dressing, and using the bathroom. Treating a brain or spinal cord tumor is about more than extending your life—it’s also focused on enhancing your quality of life.

Common Questions

How common are subependymomas?

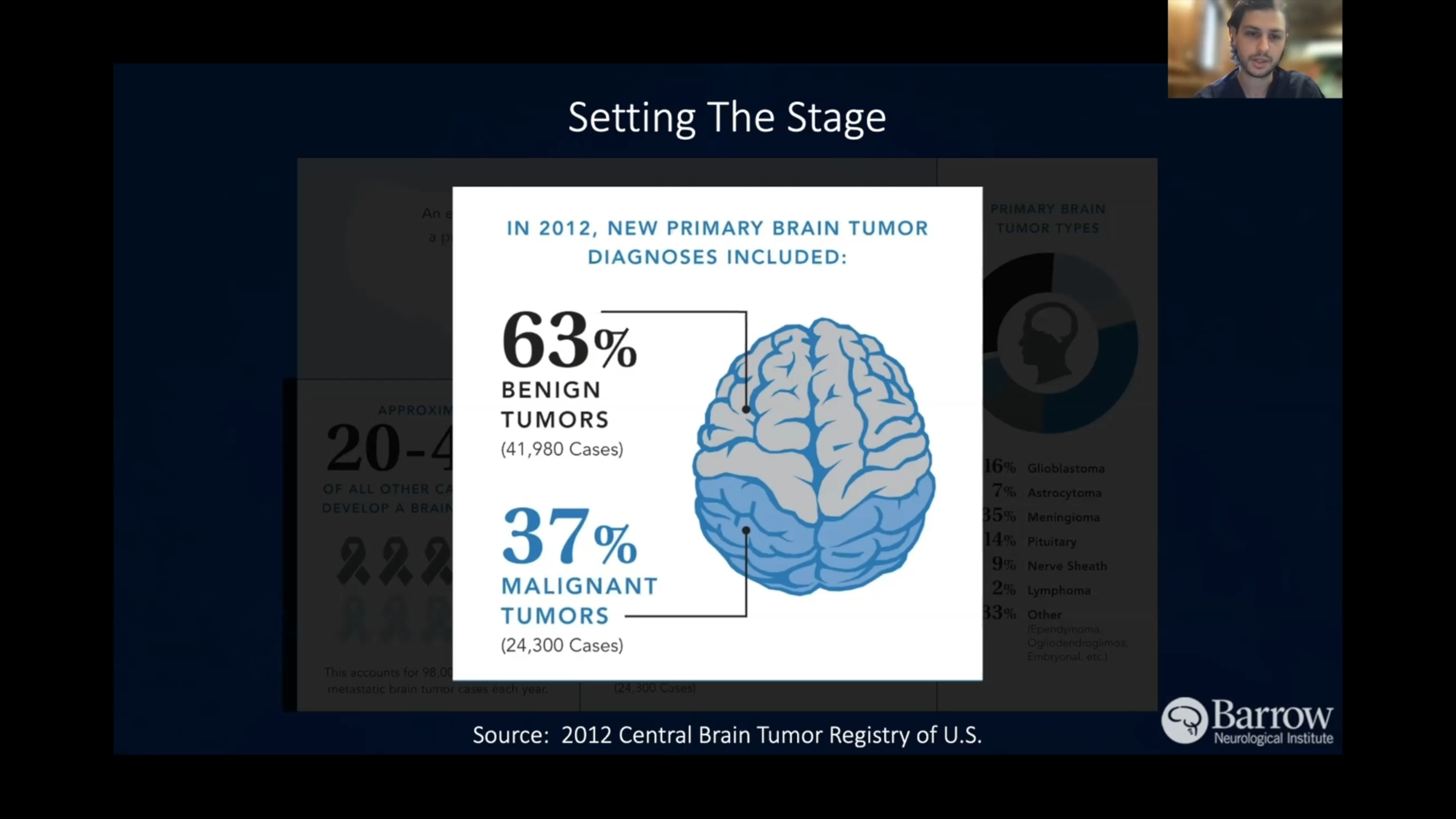

Subependymomas are uncommon, making up less than 1 percent of all brain tumors. Many are discovered incidentally on brain scans for unrelated issues, as they tend to grow slowly and may not cause symptoms.

Who gets subependymomas?

Subependymomas are usually found in adults, especially those between 30 and 60. They’re rarely seen in children and are slightly more prevalent in men than women.

What is the prognosis for those with ependymomas?

Subependymomas are benign brain tumors that infrequently spread and, when treated, have an excellent prognosis. Recurrence after complete surgical removal is rare.

Subependymomas have high survival rates, and many people experience long, symptom-free lives after diagnosis or treatment. Due to their slow-growing nature, they can remain stable for many years and, in some cases, do not require treatment.

Can subependymomas be prevented?

Genetic mutations that lead to subependymomas are believed to happen by chance. Therefore, they cannot be prevented because their exact cause is unknown.

Unlike smoking for lung cancer, subependymomas don’t have any known lifestyle, environmental, or hereditary risk factors that can be modified to reduce your risk.

Resources

References

- Chen R, Smith-Cohn M, Cohen AL, Colman H. Glioma Subclassifications and Their Clinical Significance. Neurotherapeutics. 2017 Apr;14(2):284-297. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0519-x. PMID: 28281173; PMCID: PMC5398991.

- Ferguson SD, Zhou S, Xiu J, Hashimoto Y, Sanai N, Kim L, Kesari S, de Groot J, Spetzler D, Heimberger AB. Ependymomas overexpress chemoresistance and DNA repair-related proteins. Oncotarget. 2017 Dec 15;9(8):7822-7831. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23288. PMID: 29487694; PMCID: PMC5814261.