Clinical Images: Hangman’s Fracture

Authors

Jonathan J. Baskin, MD

A. Giancarlo Vishteh, MD

Paul J. Apostolides, MD

Cameron G. McDougall, MD

Volker K. H. Sonntag, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, Mercy Healthcare Arizona, Phoenix, Arizona

Key Words : Hangman’s fracture, cervical spine trauma

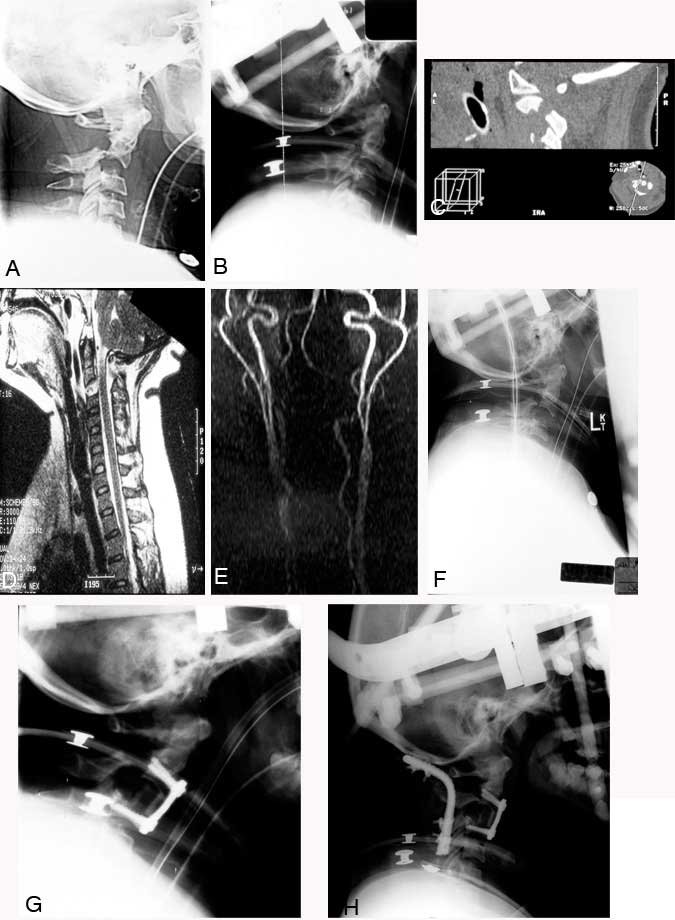

A 37-year-old woman drove her car into the back of a parked fire truck at an estimated speed of 40 to 45 miles per hour. She presented to an outside emergency department in cervical spine precautions complaining of neck pain. Her vital signs and neurological examination were normal. Traumatic disruption of the pars interarticularis at C2 identified on a cross-table lateral plain radiograph (Panel A) prompted her transfer to our institution for further management. Associated trauma included bilateral pulmonary contusions and a closed tibial fracture.

The axis fracture was reduced, and anatomical alignment was reestablished using a halo orthosis (Panel B). Computed tomography (Panel C) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (Panel D) of the patient’s cervical spine showed the fracture of the pars interarticularis. The MR image demonstrated the integrity of the spinal cord and confirmed the extent of ligamentous disruption between C2 and C3 suspected from the initial radiographs. MR angiography showed that the carotid and vertebral arteries were intact (Panel E). Serial lateral plain radiography obtained while the patient was maintained supine in bed before surgery documented profound instability of the fracture (Panel F). At no point did the patient complain of worsening neck pain or the onset of new symptoms, and her neurological examination remained normal.

An initial attempt was made to stabilize the fracture with an anterior cervical discectomy at C2-C3, followed by placement of an allograft strut graft and plate fixation. The tibial fracture was stabilized under the same general anesthesia. The patient was maintained in her halo orthosis, and postoperative imaging demonstrated good purchase of the screws and positioning of the plate (Panel G). However, the extent of posterior ligamentous incompetence was thought to impose too great a mechanical strain on the anterior fusion construct. Consequently, 2 days later she underwent posterior occipitocervical fusion with a titanium Steinmann pin and sublaminar wires. The occiput and the lamina of C3 and C4 were incorporated as fixation points to provide a stable construct to promote fusion (Panel H). At surgery, a posttraumatic dural tear was repaired between the posterior elements of C1 and C2. The patient was maintained in her halo brace and discharged from rehabilitation therapy 3 weeks later with no evidence of a neurological deficit.

Most contemporary hangman’s fractures are produced as a result of cervical hyperextension and axial compression. This patient’s circumstance is unique because her mechanism of injury closely replicates the vector of hyperextension and axial distraction that would be anticipated to cause fatal disruption of the cervicomedullary junction. The deliberate production of this fracture type during judicial hangings is the basis for this type of fracture previously receiving the eponym of “hangman’s” fracture.