What Do Patients Need Several Years After Brain Injury?*

George P. Prigatano, PhD

Division of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

*The ideas expressed in this paper were presented in part at a workshop for the Dutch Neuropsychological Society in Amsterdam, March 2000, and at the European Brain Injury Symposium (EBIS) Conference in Paris, September 2000. This paper is an English translation of a paper that was prepared for the Dutch Brain Injury Society. Reproduced with permission from Uitgeverij Lemma BV, Utrecht, Netherlands.

Abstract

At the request of the Dutch Brain Injury Association, a response to the question “What do patients need several years after brain injury?” was formulated and is presented here. It is argued that several years after brain injury, patients still need productive lifestyles. They must remain involved in educational and academic activities to the degree to which it is possible. Problems with interpersonal relationships continue, and patients often need to maintain a therapeutic alliance with an experienced clinical neuropsychologist. This statement does not mean that they need ongoing psychotherapy; rather, they need someone to talk with who understands their brain injury as problems arise several years after injury. Finally, they need an environment that helps them to accommodate their disabilities. Participation in clinical research often adds a sense of purpose to their life. Restoring and maintaining meaning in life become major issues in the rehabilitation of brain-injured patients several years after trauma.

Key Words: brain injury, neuropsychological rehabilitation

Throughout the process of evolution and during the course of a lifetime, human beings tend to adapt to external environmental demands while simultaneously attempting to actualize their unique features and potential (i.e., internal environmental demands).[5,10,11,13,22] This statement pertains to individuals with or without brain damage. Helping persons with brain damage to fulfill this psychobiological urge or tendency requires understanding the psychodynamic and neuropsychological underpinnings of mental functioning, the “rules” of learning, and the biological basis of animal behavior. In addition, clinicians must attend to and understand the conscious and unconscious communications of patients as they attempt to cope with the effects of a particular form of brain damage in the context of their life.

How is this goal accomplished? To answer this question we must first consider what has been learned in the last 75 years as clinicians and researchers have attempted to help individuals recover and adapt to the permanent effects of brain injuries. Armed with a historical perspective, we can begin to sketch what individuals might need several years after they have sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Early Observations

(1) The process of recovery after brain injury remains poorly understood.[7] Long-term change is sometimes possible.

(2) The size of a brain lesion profoundly affects the recovery process.[17] Complete recovery after severe brain injury may not be possible.

(3) The location and nature of a brain insult influence the specific constellation of neurological and neuropsychological deficits or symptoms.[18]

(4) A systematic retraining program may facilitate recovery and allow “partial” restoration of function.[18]

(5) Symptoms after brain disorder also can reflect an organism’s struggle to adapt to the injury or the tendency to avoid the struggle.[10,11] As a corollary, the management of a catastrophic reaction can be of considerable practical importance in helping brain dysfunctional patients function in daily life.

Later Observations

(1) Brain-damaged soldiers (and civilians) can be taught to improve their psychosocial functioning without necessarily improving their underlying cognitive functioning.[2,10]

(2) Small-group experiences and specific cognitive remediation tasks may help patients to improve their psychosocial functioning.[2]

(3) How patients talk about their brain injury and the symbolic methods that they use to reflect what they experience after their brain injury are greatly influenced by their premorbid personality characteristics.[32]

(4) The act of communication not only describes experience but helps define experience. Sapir noted this point years ago.[24] Thus, the symbols that individuals use to communicate about their own brain damage can be a valuable source of information that cannot be obtained by standardized or neuropsychological methods.[22]

(5) Psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic interventions can substantially help some patients to cope emotionally with their disabilities and to reestablish meaning in their life.[20-22,25,27]

(6) A neuropsychological analysis of higher cerebral functions and the way patients naturally compensate for impairments is crucial to develop realistic rehabilitation programs.[15,18,22]

(7) Many brain dysfunctional patients have some disorder of self-awareness. Therefore, entering their phenomenological field helps establish a working or therapeutic alliance with them.[22]

(8) The establishment of a working alliance with brain dysfunctional patients and their family is associated with patients achieving a productive lifestyle after neuropsychological rehabilitation.[14,28]

(9) The application of a milieu or holistic neuropsychological rehabilitation programs, traditional methods of rehabilitation, or both to the treatment of brain dysfunctional patients who have not achieved a productive lifestyle on their own can improve their productivity and help them to reduce their negative emotional reactions.[26-28]

(10) The application of these programs to patients during the acute phase of their brain injury may be a waste of time and money.[23,29] Moreover, omitting the crucial ingredient of psychotherapeutic intervention may result in considerably fewer favorable outcomes.[30]

(11) The emergence of excessive negative emotional reactions after neuropsychological rehabilitation (such as enhanced aggression) suggests that rehabilitation interventions were poorly timed[29] or that inexperienced or frankly incompetent therapists were unable to deliver adequate rehabilitation services in a clinically sensitive and sensible manner.[3,22]

(12) Effective management of the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team who provides neuropsychological rehabilitation is challenging. Without proper clinical training and guidance, the rehabilitation team can treat some brain dysfunctional patients punitively.[22] Such punitive behavior emerges because working with or interacting with severely brain-injured people increases the anxiety and distress level of caregivers.[6,8]

(13) The process of adaptation to the permanent losses imposed by brain injury is highly individual. Certain guidelines, however, can help patients (and family) with this process.[22] Outcomes depend on the clinician’s skill and understanding of the mechanisms of change observed in a given person and on the clinician’s capacity to help patients relate to symbols that reflect their efforts to cope with environmental demands while still expressing their individuality. The symbols of work, love, and play may be helpful in this regard.[22]

(14) The ultimate goal of neuropsychological rehabilitation is to foster this process in the context of helping patients to do the following: to engage the environment; to become aware of their residual strengths and weaknesses; to develop a sense of mastery over some sphere of their life; to develop, as a result, some sense of personal control; to achieve social integration; and, ultimately, to help individuals approach their suffering with what Jung called “a sense of philosophical patience.”[13,22] If done properly, this process can be tremendously helpful to both patient and family.

Observations Regarding Change After Brain Injury

(1) There may be no such thing as a “static” brain lesion.[9]

(2) With time, some neuropsychological disturbances may improve while others may decline.[31]

(3) A proportion of TBI patients who suffered a penetrating brain injury in combat may have deteriorated more than the normal aging process would predict.[4]

Long-Term Needs of Brain Dysfunctional Patients

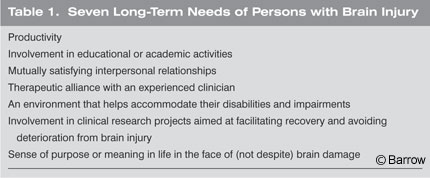

Given these observations, what are the long-term needs of brain dysfunctional patients? My interpretation of the scientific and clinical observations listed above suggests that patients have at least seven major needs (Table 1).

The first is the need to be productive. As discussed by Hall and Lindzey,[12] Eric Erickson outlined different stages of psychosocial development. Erickson noted that when individuals are unable to be productive or to generate something “new,” they stagnate and their personality may regress. This observation is clearly true of brain dysfunctional patients. They need a job. They need to do something that is helpful to someone else. Some patients may need to receive financial compensation for their work while others may not. As Erickson articulated, however, individuals without an ongoing commitment to be productive often stagnate.

Second and perhaps less obvious, brain dysfunctional patients need to be involved in some type of educational or academic activity throughout their life. Given their cognitive limitations, this need may seem paradoxical. Recent research on Alzheimer’s disease,[22] however, shows that more highly educated individuals often show less early and possibly less rapid decline in their cognitive status when they develop Alzheimer’s disease compared to individuals with less education. New reviews of brain function and organization emphasize the dynamic nature of the brain and how it either develops for the better or the worse. Education and educational activities may play some protective role in the deterioration of higher brain functions. No one has studied whether effective neuropsychological rehabilitation has a protective role as brain-injured individuals age, but it may for some individuals. Developing appropriate educational settings for the elderly with a TBI is seldom pursued but highly desirable.

A third need of brain dysfunctional patients (as well as of nondysfunctional patients) is the ability to sustain mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships. Humans are social beings and, without intimacy, often become isolated, as Erickson noted. Social isolation is a common, long-term consequence of TBI.[16] Brain dysfunctional patients need help to avoid social isolation, a goal best accomplished by helping them to maintain mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships and to meet the first two needs as outlined above.

Fourth, as they age, many patients need to maintain a therapeutic alliance with an experienced clinician. This statement does not mean that patients need ongoing psychotherapy throughout their life. It only means that they need to be in contact with an experienced clinician who can help guide them during difficult times. Such a therapeutic alliance relates to neuropsychological outcomes.[28] As outlined elsewhere,[25] various psychotherapeutic interventions can be quite helpful for brain dysfunctional patients several years after brain injury.

Fifth, brain dysfunctional patients need to be placed in an environment that accommodates their cognitive and physical disabilities and impairments. This need is perhaps the most obvious. Patients need safe physical environments as well as the opportunity to exercise and to improve their stamina and to reduce their fatigue. Typically, the more physically mobile and active that individuals are, the greater is their quality of life. Ideally, a psychosocial environment that accommodates patients’ cognitive and personality difficulties is needed, but practically it is difficult to obtain. In these terms, much work is needed. The establishment of a milieu or therapeutic environment is helpful in rehabilitating brain dysfunctional patients;[26] the same broad model could be applied to their long-term needs.

The sixth need of brain dysfunctional patients is less obvious: They need to become actively involved in clinical research projects that may help to facilitate their recovery and to avoid their deterioration. Many studies are being conducted worldwide on the various roles of pharmacological interventions to diminish the effects of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain dysfunctional patients may also benefit from being involved in pharmacological or behavioral studies aimed at helping to improve their function. Perhaps idealistic, this issue still needs to be considered.

Perhaps the final need of brain dysfunctional patients is the most important. Patients need to experience a sense of purpose or meaning in their life in the face of (not despite) their brain damage. This task is difficult but crucial. Luria’s book, The Man with a Shattered World, highlights how one individual regained meaning by sharing the story of his brain injury.[19] Other patients find meaning by supporting their spouse’s efforts, by helping their family members, by being creative in terms of artistic expression, and so on. The means by which a given individual experiences meaning can vary. However, without this sense of meaning, individuals frequently slip into a sense of despair, particularly as they age and must cope with the long-term effects of their brain injury in addition to the process of aging.

How Can the Needs of Brain Dysfunctional Patients Be Met?

Based on what is known about recovery and rehabilitation efforts after brain injury, how can the seven long-term needs of brain dysfunctional patients be met? Meeting any “need” is, of course, an ongoing process that only ends with death. Nowhere is there a “Mecca” for patients with these seven long-term needs. Given their environment and available resources, each person who suffers a brain injury must work with their family and friends to try to meet these needs as best as possible. How these needs might ideally be met over time can be conjectured. The following discussion focuses on brain dysfunctional individuals who are now in their mid50s and who sustained a severe TBI 20 to 30 years earlier.

To help brain dysfunctional patients be productive, they should meet with, on an individual basis, an experienced clinical neuropsychologist who understands how brain injury affects a myriad of higher cerebral functions. That clinical neuropsychologist should help the patient to enter small groups in which other brain-injured individuals struggle with whether they can be productive. Many brain dysfunctional patients have an unrealistic view about their capacity to be productive. Some feel that they are totally useless and unable to do any work; others insist that they can work despite significant cognitive and personality disturbances. By working with such patients in small groups, a clinical neuropsychologist can help some of them to achieve a realistic perspective of what type of work they could potentially do. The group dynamics can help convince some patients to try a certain level of work that they might not otherwise be willing to consider.

Having patients begin some type of productive activity and having them meet periodically in long-term support groups to discuss both their frustrations and successes seem useful strategies that need not be costly ventures. Family members, however, must encourage and support brain dysfunctional patients to attend groups intended to help them maintain a productive stance. Once brain-injured patients find their “niche,” many want to work because it is a natural psychobiological urge as noted above.

For example, a business executive could not read after an arteriovenous malformation involving his left occipital lobe and splenium of the corpus callosum ruptured. Yet, he was only willing to work as a high-level manager. Because he could not read, he felt that no work would be satisfactory to him. Through the efforts of experienced therapists, it was discovered that he enjoyed history. Eventually, he was helped to serve as a guide in a museum. The therapist put the necessary historical information on audio tapes for him to listen to and rehearse. He thereby learned the information, which he could then present to visitors at the museum, despite his severe reading disability. Finding innovative ways to compensate for cognitive deficits (and sometimes personality disturbances) is crucial to help patients maintain work. From my perspective, individuals should be productive and work for as long as they can. Retirement is possible if individuals remain active in some capacity. Otherwise, retirement simply means stagnation and ultimately a meaningless existence.

How should the educational and academic needs of brain dysfunctional patients be met? As long as the brain is alive, it can learn. Many brain dysfunctional patients still crave knowledge and desire to learn. This normal, human urge has biological and psychological underpinnings. One possibility is small group meetings at the local library to review materials that might be of interest to different types of brain dysfunctional patients. Participants could read or at least listen to simple discussions regarding topics of interest. The core issue is to develop an educational environment that is neither too demanding nor too basic. Good teachers are needed at every stage of life for all individuals–with or without brain injury. Hospitals could also provide long-term support groups with an educational component for brain dysfunctional patients.

The need to establish mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships is complicated and requires a certain degree of psychological and interpersonal development. Therapists should not be discouraged when trying to help patients achieve this more ambitious goal. One place to begin is by asking patients who in their life is most important to them? The next question is how can they can enhance the quality of life of that other person. This issue should be discussed regularly. For example, an elderly gentleman who suffered a stroke felt totally impotent to do anything for his wife. She took care of the bills, cooked, cleaned house, and so on. A simple thank you seemed inadequate. However, he recognized that she enjoyed receiving little “love notes” from him. At the encouragement of an experienced psychotherapist, he obtained 365 thank-you cards. Each day he wrote something loving and humorous and placed a card under his wife’s pillow when she took her shower. He exerted effort to give something to his wife; in turn, she gave back to him. This type of encouragement is important for brain dysfunctional patients and could also be accomplished in some of the group settings discussed above.

The need to establish a therapeutic alliance with an experienced clinician can be inhibited by patients’ or family’s limited financial resources. In such cases, society and government should help. State or governmental agencies should provide the funds for brain dysfunctional patients to meet periodically with an experienced psychotherapist who understands the effects of brain injury on psychological functioning. An alliance should be maintained over several years so that it can be drawn upon when patients run into difficult times. For example, a 55-year-old gentleman who had sustained significant frontal lobe damage in his early 20s was followed for more than 30 years. He did not really understand the consequences of his brain injury, but he did trust the clinical neuropsychologist who had evaluated him and who had tried to guide him in dealing with daily problems. When the patient’s mother eventually died, he turned to the psychologist for support and help. When he was confronted with deciding what living circumstances would be best for him by himself, he also turned to the psychologist. The value of this type of therapeutic alliance should not be minimized. It is extremely important for patients who have difficulty making good judgments on their own.

For the fifth need, how do we establish adequate environments that appropriately address the physical and cognitive disabilities and impairments of brain dysfunctional patients? An answer to this question is perhaps the most difficult to envision. Society has decreased barriers for individuals with physical impairments. Individuals in wheelchairs, for example, have easier access to many facilities compared to the past. Yet, many barriers remain. For example, brain dysfunctional patients can be insensitive. They can be argumentative. They can show apathy. They can develop paranoid ideation. They can be forgetful. They can appear unkempt. These characteristics ultimately isolate patients socially. Society and professional communities have yet to find a good way to establish environments that appropriately accommodate such disabilities. Animal models suggest that the process of evolution may have bestowed in humans an intolerance for behaviors associated with brain damage.[8] Rehabilitation, however, is a uniquely human venture. As professionals, therapists have the responsibility to help brain dysfunctional patients try to develop communities that permit them some capacity for a social life. Because it involves other individuals, fulfilling this need will likely be the most difficult. Ultimately, education that raises the awareness of society may be the key.

Stating that brain dysfunctional patients need to be involved in clinical research may seem to reflect the needs of researchers more than those of patients. This, however, is not the case. Brain dysfunctional patients often wonder why they have the problems that they have. When they receive appropriate explanations, they often find research projects highly interesting. They become willing to participate in studies, particularly if others’ quality of life might improve. Brain injury does not always reduce altruistic tendencies, and it can be important for these individuals to give “something” back to society. Meeting this need can also help patients to meet their final need-establishing meaning in their life. If patients are actively involved in a number of pharmacological or behavioral studies aimed at improving recovery from brain injury, they may well benefit from new insights. Governments should seriously consider keeping a register of all brain dysfunctional patients treated in different regions and actively encouraging their participation in research with financial rewards. Despite the idealism of this notion, it would likely be associated with enough benefits to justify the expense.

The final need, the need to establish meaning in life, is undoubtedly achieved through many paths. As I have written previously, the ability to work, love, and play (enter fantasy) is perhaps one of the best recipes for establishing meaning in our Western culture. These symbols of work, love, and play translate, respectively, to being productive, to establishing mutually satisfying relationships, and to expressing individuality through playful thoughts or actions. When individuals behave authentically and enjoy interacting with others, their meaning in life is clear. When individuals stifle their individuality, when they cannot work, when they cannot sustain intimate relationships, life loses meaning. Individuals can become depressed and consider suicide. What bestows meaning given the realities of their physical and cognitive limitations should be discussed constantly with brain dysfunctional patients and their families. In medical settings, physicians often attend to the physical needs of patients but not necessarily to their psychological needs. Therefore, it is extremely important for clinicians to maintain a broader perspective and to maintain discussions of meaning in life at the forefront of therapeutic interactions as brain dysfunctional patients age.

Who Benefits from Neuropsychological Rehabilitation and Why?

In reflecting on the long-term needs of persons with TBI, it is worthwhile to reflect on who benefits from holistic, milieu-oriented neuropsychological rehabilitation and why?

Patients who benefit have the brain reserve capacity to learn from their experiences and to be productive and independent in some manner. They can learn to improve their self-awareness or if their awareness does not return to normal, they can accept guidance in their choices from someone they trust. They can learn to control their emotional reactions, especially negative emotional reactions, and to relate to symbols that provide meaning in their life. Finally, such patients are fortunate enough to be guided by therapists who know what they are doing.

Reflecting on their clinical work, Ben-Yishay and Daniels-Zide asked who optimally benefitted from efforts at holistic neuropsychological rehabilitation.[1] From their perspective, individuals who achieved an optimal outcome had achieved an “examined life.” They made healthy choices and functioned within the guidelines of those choices. They achieved a certain degree of inner peace or contentment by accepting themselves within their existential situation. In essence, they achieved a realistic sense of ego identity–basically an Ericksonian and neoFreudian perspective.

My reflections share much with those of Dr. Ben-Yishay’s, but my perspective is more Jungian than psychoanalytic. With or without a history of brain injury, people struggle with a basic paradox: They must constantly respond to the external environment to make their niche, but they simultaneously seek self-expression. That is, they seek environments that permit them to be uniquely who they are and what they want to be.

From my perspective, people who benefit the most are those who can successfully relate to the symbols of their culture that help provide meaning. In our culture, these symbols are work, love, and play and suggest that individuals must remain productive and have satisfying interpersonal relationships. Ego identity, however, is not an end product. It is a continued search to develop one’s uniqueness. Choices are important, but the most important choice is to “be true to one’s self.” Living with one’s authentic self helps to bestow meaning in life.

Following this path requires taking chances as well as making choices. It is difficult with or without a brain injury but crucial for a real life-a life filled with passion, pain, pleasure, joy, sadness, insight, and stupidity. Ultimately, it offers a truly human perspective on what it means to be alive and to have the courage to live. From my perspective, this is what people need several years after a brain injury.

References

- Ben-Yishay Y, Daniels-Zide E: Examined lives: Outcomes after holistic rehabilitation. Rehabilitation Psychology 45:112-129, 2000

- Ben-Yishay Y, Diller L: Rehabilitation of cognitive and perceptual defects in people with traumatic brain damage. Int J Rehabil Res 4:208-210, 1981

- Brooks N, McKinlay W, Symington C, et al: Return to work within the first seven years of severe head injury. Brain Inj 1:5-49, 1987

- Corkin N, Rosen TJ, Sullivan EV, et al: Penetrating head injury in young adulthood exacerbates cognitive decline in later years. J Neurosci 9:3876-3883, 1989

- Darwin C: The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965

- Florian V, Katz S: The other victims of traumatic brain injury: Consequences for family members. Neuropsychology 5:267-279, 1991

- Franz SI: Studies in re-education: The aphasias. Comparative Psychology 4:349-429, 1924

- Franzen EA, Meyers RE: Neural control of social behavior: Prefrontal and anterior temporal cortex. Neuropsychologia 11:141-157, 2002

- Geshwind N: Mechanisms of change after brain lesions, in Nottebohm F (ed): Hope for a New Neurology. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1985, pp 4-11

- Goldstein K: Aftereffects of Brain Injury in War. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1942

- Goldstein K: The effect of brain damage on the personality. Psychiatry 15:245-260, 1952

- Hall CS, Lindzey G: Theories of Personality. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1978

- Jung CG: The Practice of Psychotherapy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University, 1957

- Klonoff PS, Lamb DG: Outcome assessment after milieu-oriented rehabilitation: New considerations. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79:684-690, 1998

- Kolb B: Recovery from occipital stroke: A self-report and an inquiry into visual processes. Can J Psychol 44:130-147, 1990

- Kozloff R: Network of social support and the outcome from severe head injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2:14-23, 1987

- Lashley KS: Factors limiting recovery after central nervous lesions. J Nerv Ment Dis 88:733-755, 1938

- Luria AR: Restoration of Function After Brain Trauma (in Russian). London: Academy of Medical Science (Pergamon), 1963

- Luria AR: The Man with a Shattered World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972

- Prigatano GP: Disordered mind, wounded soul: The emerging role of psychotherapy in rehabilitation after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabilitation 10:87-95, 1991

- Prigatano GP: 1994 Sheldon Berrol,MD, Senior Lectureship: The problem of lost normality after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabilitation 10:87-95, 1995

- Prigatano GP: Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999

- Prigatano GP: Letter to the editor on rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. JAMA 284:1783, 2000

- Prigatano GP, Ben-Yishay Y: Edwin A. Weinstein’s contributions to neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 6:305-326, 1999

- Prigatano GP, Ben-Yishay Y: Psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic interventions in brain injury rehabilitation, in Rosenthal M (ed): Rehabilitation of the Adult Child with Traumatic Brain Injury. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1999

- Prigatano GP, Fordyce DJ, Zeiner HK, et al: Neuropsychological rehabilitation after closed head injury in young adults. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 47:505-513, 1984

- Prigatano GP, Fordyce DL, Zeiner HK, et al: Neuropsychological Rehabilitation After Brain Injury. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1986

- Prigatano GP, Klonoff PS, O’Brien KP, et al: Productivity after neuropsychologically oriented, milieu rehabilitation. J Head Trauma Rehabilitation 9:91-102, 1994

- Salazar AM, Warden DL, Schwab K, et al: Cognitive rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. A randomized trial. Defense and Veterans Head Injury Program (DVHIP) Study Group. JAMA 283:3075-3081, 2000

- Scherzer BP: Rehabilitation following severe head trauma: Results of a three-year program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 67:366-374, 1986

- Thomsen IV: Late outcome of very severe blunt head trauma: A 10-15 year second follow-up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 47:260-268, 1984

- Weinstein EA, Kahn RL: Denial of Illness. Symbolic and Physiological Aspects. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1955