The Case for Designated Neurotrauma Referral Centers in the United States

Authors

M. Ross Bullock, MD, PhD

P. David Adelson, MD

Donald W. Marion, MD

Katie Orrico, JD

Jamshid Ghajar, MD, PhD

The Joint Section of Neurotrauma and Critical Care, American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurosurgeons; The Brain Trauma Foundation, New York, New York; and Division of Neurosurgery, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia

Abstract

The effect of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) laws and changing patterns of availability of neurosurgeons mean that neurotrauma victims may not always receive the best quality of care and thus may not achieve an optimal outcome. By voluntary designation and subsequent inspection and accreditation, hospitals that meet certain standards of neurotrauma care could select themselves to receive neurotrauma patients preferentially, and thus provide optimal care for these patients.

Key Words: EMTALA, neurosurgery, neurotrauma, trauma care systems

Throughout the world, trauma continues to be the leading cause of death and disability. Most of the deaths and almost all of the severe prolonged disability caused by trauma involves damage to the nervous system. Better designed automobiles and highways and more intensive policing have helped to achieve a decline in the incidence of closed head injury from motor vehicle accidents. Concomitantly, however, penetrating brain and spinal cord injuries have increased in almost all urban centers in the United States as handgun violence has increased. In many states motorcycle helmet laws have been repealed, and severe head injuries have rebounded as a result.

Every year in the United States, more than a million individuals visit emergency rooms with head injuries: 50 to 60,000 die from a severe head injury and about 250,000 are admitted to hospitals. About 8,000 to 10,000 new spinal cord injuries occur every year, and most cause permanent disability.[4] In the United States, the aggregate cost of severe head injury alone has been estimated around $48 billion/year. [8]

To deal with this enormous trauma problem, a federally mandated national, state, and local regional trauma care coordination system has evolved in the United States. This system has become a model that is emulated throughout the world. Data show that the rates of death and disability for trauma management has steadily declined in most regions of the United States as this system has been refined.[8,11] Furthermore, evidence shows that management of patients with severe traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), in accordance with evidence-based guidelines, has reduced the number of poor outcomes.[5,9]

During the last 5 years, however, several powerful forces have emerged. These forces have placed the trauma system at risk and are jeopardizing care for trauma patients in general, and for neurotrauma patients, in particular. Managed care and third-party payer-mandated restrictions on care are affecting the quantity and quality of care given to trauma victims who are frequently thought of as expensive “loss leaders” by third-party payers. Shorter durations of hospital stay, shorter periods of rehabilitation, and directed hospital plans (HMOs) may mean that patients with multiple traumatic injuries are directed to receive care in community hospitals rather than in university centers where they would get the best care, albeit at a higher level of intensity and hence cost.

Community hospitals often seek to attract patients with multiple traumatic injuries. Their high level of intensity, the favorable publicity that they accrue within their communities, and the high likelihood that vehicular trauma patients will be covered by auto-insurance payers make such patients attractive. To attract all categories of neurotrauma patients, however, hospitals must meet the requirements for Level I or Level II Trauma Center certification, which mandates the availability of neurosurgeons.

Against these increasing requirements for neurosurgical involvement in trauma care, many community neurosurgeons are increasingly torn between providing high-intensity neurotrauma care and the ever-increasing demands of private practice. Several surveys indicate that many trauma centers are dissatisfied with the level of support that they receive from neurosurgeons.[12] Given the possibility of long-term impairment for a neurotrauma patient, community neurosurgeons perceive that neurotrauma patients are underinsured and represent potential involvement with litigation.[12]

Thus, market forces are propelling the dissemination of all types of trauma victims, including neurotrauma victims, to an increasingly wider diversity of hospitals. Simultaneously, the small numbers of neurosurgeons being trained in academic programs throughout this country and the even smaller numbers of these neurosurgeons who are being trained specifically in neurotrauma care mean that the involvement of neurosurgeons in neurotrauma care continues to decline. Trauma surgeons and critical care physicians have been quick to enter this arena. In parts of the United States with the lowest neurosurgical coverage, trauma surgeons have shown that they are able to provide good care to the simpler categories of neurotrauma victims such as those with hematomas.[10]

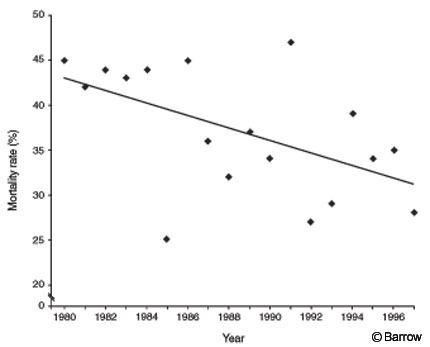

However, the increasing sophistication of care provided by a small group of neuroscience-dedicated intensive care units has shown that a steady decrease in the mortality rate of patients with severe head injuries is not associated with prolonged disability as had been feared by many (Fig. 1). Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) is the major cause of death in patients with severe head injury. Neurosurgeons are best equipped to treat patients with high ICP. Therefore, the best quality of care for patients with a severe head injury belongs in the hands of specialized centers with significant expertise in treating high ICP.

Treatment may include measures such as decompressive craniectomy and removal of contused brain. Clearly, ICP monitoring is the cornerstone of aggressive and effective care for patients with severe head injury. Yet surveys across the United States have shown that only 41% to 68% of patients who should undergo ICP monitoring (based on recently formulated and widely accepted guidelines), in fact, receive this care.[3]

The Case for Neurosurgical Involvement in Spinal Cord Injury Care

Recently, guidelines for the management of patients with spinal cord injury based on the principles of evidence-based medicine were formulated.[1] These guidelines endorse the view that a cornerstone in the management of the spinal cord-injured patient is aggressive resuscitation of pulse and blood pressure. At least 25% of spinal cord-injured patients will have concomitant major injuries, and such patients should be managed in an experienced trauma center.[13]

Increasingly, class III evidence supports the view that early stabilization of unstable fractures and decompression of a compressed spinal cord offers patients the best chance for long-term recovery. Such surgical procedures are often highly complex, requiring instrumentation and sometimes anterior transthoracic or transabdominal approaches. This expertise is most likely to be available in centers with experienced spinal surgeons and in those with established relationships among trauma surgeons, general surgeons, thoracic surgeons, and neurosurgeons.[2]

Proposed Voluntary Designation of Specialized Neurotrauma Centers

Based on the foregoing arguments, the Trauma Section of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons has proposed and endorsed the view that a national system of designation and accreditation should be implemented in the United States to recognize and develop centers with specialized neurotrauma expertise. It is proposed that such centers should volunteer themselves to be so designated and that a system of inspection and accreditation, as currently performed by the American College of Surgeons for Level I Trauma Center accreditation, should be implemented. A similar inspection and accreditation system is in place for statewide Level I Trauma Center accreditation.[6] In the state of Florida, such a neurotrauma designation system is already in place but lacks inspection and accreditation.

Benefits Accruing from Neurotrauma Accreditation

Numerous benefits may accrue to individual centers that achieve neurotrauma accreditation. First, in some states, state subsidies are available to support institutions that provide high-quality neurotrauma care. Second, when faced with the existing evidence that outcomes for neurotrauma patients are much better in centers with expertise in neurotrauma care, third-party payers, such as HMOs, may choose specifically to fund care for neurotrauma victims only in centers with demonstrated expertise based on their designation as neurotrauma centers. Third, prehospital providers would rapidly develop patterns of referral for neurotrauma patients so that most patients would go to neurotrauma-designated centers. Similarly, ambulance and helicopter systems in each state would facilitate triage of victims of severe neurotrauma (i.e., head injury with altered consciousness, suspected spinal cord injury with neurological deficit) to hospitals that could best provide their care.

Benefits for Neurotrauma Victims

Neurotrauma victims who obtain their care at designated neurotrauma centers will benefit from the higher level of expertise and intensity of care available at such centers. Such a benefit has been established for patients with myocardial infarction who are taken to hospitals with designated expertise in the care of heart attack victims.[7]

Benefits for National Trauma Care Systems and Physicians

If most neurotrauma victims are concentrated in hospitals with special expertise for their care, those centers will achieve higher volumes. In turn, their high volumes will facilitate excellence in care. It will also facilitate teaching the principles of neurotrauma care to specialized nurses and physicians, including trauma surgeons, neurosurgeons, and critical care specialists.

Concentrating neurotrauma patients at centers with the most expertise for their care will also facilitate the rapid completion of research studies. A major limiting factor that has prevented the development of effective neuroprotectant drugs has been the wide disparity in the quality of neurotrauma care provided across the centers enrolling patients in such drug trials.[7] In many trials, more than half the centers enroll only one or two patients throughout the 2- to 3-year duration of a drug trial. Such inhomogeneity means that trials are much more difficult to perform and translates into a need for larger numbers of patients.[7]

Possible Criteria for Neurotrauma Center Designation

There are eight potential criteria that institutions might fulfill to be designated as a neurotrauma center. First, they should have demonstrated experience with ventriculostomy and other types of ICP monitoring (suggest 20 per year or more). Second, they should have experience with decompressive craniectomy and duraplasty. Third, they should have experience with internal decompression and resection of contusions. Fourth, a dedicated neuroscience intensive care unit should be available. Fifth, two or more neurosurgeons with specific expertise in neurotrauma management should be available. Sixth, a neurosurgical/thoracic surgical/trauma team with experience in the stabilization of complex spinal fractures should be available. Seventh, the center should have expertise in conducting neurotrauma clinical trials. Finally, a well-developed helicopter or fixed-wing air transport network should be available to the hospital.

Effect of COBRA and EMTALA Laws on Neurotrauma Center Designation

The “antidumping” intent of current legislation means that many hospitals and their attendant trauma providers, especially neurosurgeons, are anxious to avoid violating federal statutes by transferring trauma victims to other hospitals. A cornerstone of a neurotrauma designation system would be that the designation would indemnify hospitals that transfer neurotrauma victims to designated trauma centers.

Who Would Perform Neurotrauma Accreditation?

Once the criteria for neurotrauma designation have been established, inspection and accreditation could be performed by a committee of individuals nominated by the Neurotrauma Section of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the American College of Surgeons, and members of the major trauma societies (i.e., ASCOT and EAST).

How Would Neurotrauma Centers Be Distributed Across the United States?

Based on current incidence figures, a designated neurotrauma center would optimally serve 3,000,000 to 5,000,000 people. These figures translate into 70 to 100 trauma centers across the United States. Most centers with an established reputation for neurotrauma care would likely become busier with such a designation and may need to hire additional personnel to provide this level of care.

Conclusions

A neurotrauma designation system would empower physicians who wish to treat neurotrauma victims to do so more effectively. It would allow individuals unfortunate enough to sustain severe neurotrauma to obtain the best possible care. Improved care will optimize these patients’ chances for the best possible recovery, which will decrease the enormous cost of neurotrauma in our society.

References

- Guidelines for management of acute cervical spinal injuries. Introduction. Neurosurgery 50 (3 Suppl):S1, 2002

- Fehlings MG, Tator CH: An evidence-based review of decompressive surgery in acute spinal cord injury: Rationale, indications, and timing based on experimental and clinical studies. J Neurosurg 91:1-11, 1999

- Hesdorffer DC, Ghajar J, Iacono L: Predictors of compliance with the evidence-based guidelines for traumatic brain injury care: A survey of United States trauma centers. J Trauma 52:1202-1209, 2002

- Kraus JF, McArthur DL: Epidemiologic aspects of brain injury. Neurol Clin 14:435-450, 1996

- Mcilvoy L, Spain DA, Raque G, et al: Successful incorporation of the Severe Head Injury Guidelines into a phased-outcome clinical pathway. J Neurosci Nurs 33:72-78, 2001

- Mullins RJ, Veum-Stone J, Hedges JR, et al: Influence of a statewide trauma system on location of hospitalization and outcome of injured patients. J Trauma 40:536-546, 1996

- Narayan RK, Michel ME, Ansell B, et al: Clinical trials in head injury. J Neurotrauma 19:503-557, 2002

- NIH Consensus Panel: NIH Consensus Development Panel on Rehabilitation of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury. NIH Consensus Development Conference, Bethesda, MD, 1998

- Palmer S, Bader MK, Qureshi A, et al: The impact on outcomes in a community hospital setting of using the AANS traumatic brain injury guidelines. American Association for Neurological Surgeons. J Trauma 50:657-664, 2001

- Rinker CF, McMurry FG, Groeneweg VR, et al: Emergency craniotomy in a rural Level III trauma center. J Trauma 44:984-990, 1998

- Thurman DJ, Jeppson L, Burnett CL, et al: Surveillance of traumatic brain injuries in Utah. West J Med 165:192-196, 1996

- Valadka AB, Andrews BT, Bullock MR: How well do neurosurgeons care for trauma patients? A survey of the membership of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Neurosurgery 48:17-24, 2001

- Vale FL, Burns J, Jackson AB, et al: Combined medical and surgical treatment after spinal cord injury: Results of a prospective pilot study to assess the merits of aggressive resuscitation. J Neurosurg 87:239-246, 1997