Pituitary Tumors

Overview

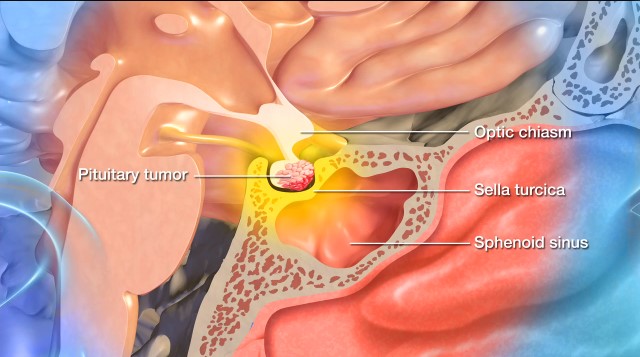

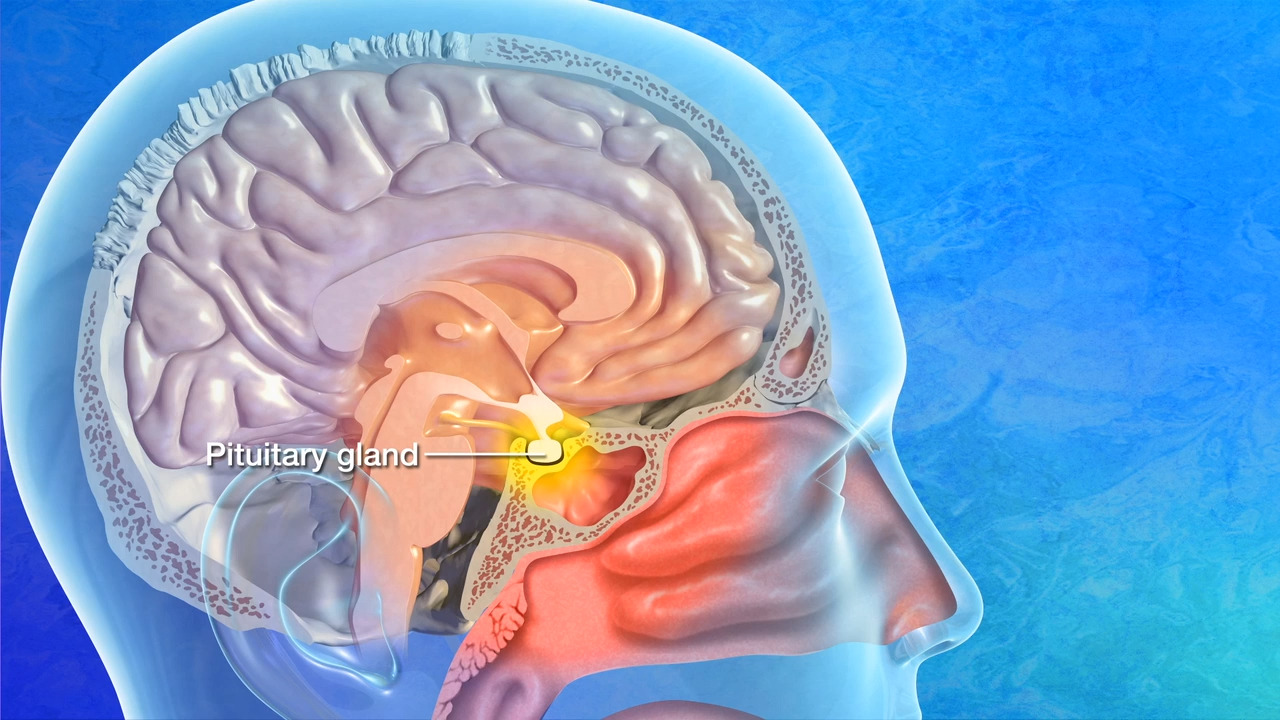

A pituitary tumor is an abnormal growth of cells within or around the pituitary gland, a pea-sized organ at the base of the brain, behind the bridge of the nose.

Most pituitary tumors are noncancerous or benign growths called adenomas. While pituitary adenomas do not spread to other parts of the body, they can cause the pituitary gland to produce too many or too few hormones. They can also press on nearby nerves, especially the optic nerves causing visual disturbance, other parts of the brain, or the pituitary gland itself.

However, most pituitary tumors don’t cause symptoms or affect hormone levels, so they’re often undiagnosed or found incidentally after a routine imaging or blood testing.

Neurosurgeons and neuroendocrinologists generally divide pituitary tumors into three main groups based on their behavior. They include:

- Functional tumors: These are pituitary tumors that produce hormones, and they’re more likely to be diagnosed because they cause noticeable symptoms. Types of functional pituitary tumors include:

- Prolactinomas: The most common type of functional pituitary tumor, prolactinomas secrete prolactin. This hormone plays a key role in breast development and lactation.

- Growth hormone-secreting tumors: These tumors overproduce growth hormone (GH), which can lead to acromegaly in adults and gigantism in children.

- ACTH-secreting tumors: These tumors produce adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which leads to the overproduction of cortisol and causes Cushing’s disease.

- TSH-secreting tumors: These are extremely rare tumors that produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which causes hyperthyroidism, or overactivity of the thyroid gland.

- Gonadotropin-secreting tumors: Another rare type of pituitary tumor, these secrete luteinizing hormone (LH) or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) that can disrupt reproductive functions.

- Nonfunctional tumors: These are the most common type of pituitary tumors and they do not produce excessive hormones. Doctors often discover them when they grow large enough to cause symptoms by pressing on nearby brain structures (mass effect) or when they cause reductions of pituitary hormones that manifest as symptoms.

- Pituitary carcinomas: These are very rare (less than 0.2 percent of all pituitary tumors) and can metastasize or spread to other parts of the body.

Doctors use the following guidelines to categorize pituitary adenomas further:

- Microadenoma: This pituitary tumor measures less than 1 centimeter (cm). Most pituitary tumors fall into this category.

- Macroadenoma: This pituitary tumor measures more than 1 centimeter (cm).

What causes a pituitary tumor?

The exact causes of pituitary tumors are not fully understood—the latest research points toward a combination of genetic, hormonal, and possibly environmental factors.

Most pituitary tumors don’t have a clear hereditary cause, and they occur in those without a family history. However, a small percentage of pituitary tumors are linked to inherited genetic conditions, such as:

- MEN1: Mutations in the MEN1 gene are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1), which increases the risk of pituitary and other endocrine tumors.

- Carney complex: A rare genetic disorder, Carney complex can cause benign tumors to grow, including pituitary tumors.

- McCune-Albright syndrome: This disorder affects the skin, bones, and endocrine system, which is responsible for producing hormones.

- Familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPA): Caused by a change in an X-chromosome gene, FIPA is a rare condition that affects a small percentage of people with pituitary adenomas. However, it can affect multiple family members.

Pituitary Tumor Symptoms

Typically, symptoms from a pituitary tumor either come from hormonal imbalances or from the tumor putting pressure on the pituitary gland or nearby structures. That said, many people with pituitary tumors don’t experience symptoms.

If you have a pituitary tumor, you might experience a combination of the following symptoms:

Symptoms caused by pituitary hormonal imbalances:

- Fatigue: This is a frequently reported symptom, as pituitary tumors can cause both hormone reduction and overproduction. This lack of hormones for energy regulation, or an excess of a hormone like prolactin, can lead to fatigue.

- Menstrual or breast changes: High prolactin levels can also result in changes to the menstrual cycle and breast discharge.

- Irregular menstruation: While these symptoms are often subtle, menstrual irregularities or cessation in your menstrual cycle can be indicative of gonadotropin-secreting tumors.

- Milk production: Unrelated to childbirth or breastfeeding, new breast milk production can signal a prolactinoma.

- Low libido: Decreasing sexual drive, as well as erectile dysfunction, can point to a prolactinoma.

- Unexplained weight gain: Sudden or unexpected weight gain, particularly in the face, upper back, and abdomen, is often caused by ACTH-secreting tumors that cause Cushing’s disease.

- Thinning skin and easy bruising: Onset of thinning skin, an easier-than-normal ability to bruise, and new stretch marks can also be symptoms of ACTH-secreting tumors.

- Mood changes: Pituitary tumors can cause mood changes, like depression or irritability, due to their effects on hormone levels and brain function.

- Unexplained sleep disruption: Hormonal imbalances, particularly cortisol-related imbalances, can disrupt the sleep-wake cycle. Poor sleep quality or even insomnia can exacerbate symptoms like irritability, fatigue, and depression.

- Unexplained weight loss: Weight loss due to decreased appetite or muscle wasting.

- Unexplained hair growth or loss: Lowered or heightened levels of certain hormones, like ACTH, can cause hair growth or loss.

- Joint pain and skin changes: Growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumors can produce a host of symptoms, including thickening skin, joint pain, enlarged hands, feet, and facial features, and rapid and excessive growth in children. In adults, this is known as acromegaly, while in children, it’s called gigantism.

- Dizziness: Hormonal imbalances and secondary effects on blood pressure can lead to dizziness.

Symptoms caused by pituitary tumor pressure (mass effect):

- Vision problems: Pituitary tumors can cause vision problems, especially double vision and loss of peripheral vision, when they crowd the optic nerves. In advanced cases, progressive vision loss or blindness can occur in one or both eyes.

- Headaches: A widespread symptom of pituitary tumors, headaches result from the tumor compressing pituitary tissue or nearby structures, leading to changes in intracranial pressure. Pituitary tumor headaches are typically focused on the forehead or behind the eyes, but can vary in location and intensity.

- Nausea and vomiting: Increased intracranial pressure can stimulate the brain’s vomiting center, leading to nausea and vomiting.

- Fatigue or weakness: Persistent pressure can lead to general fatigue, often accompanied by reduced physical or mental energy.

- Dizziness: Pressure on nearby brain structures and secondary effects on blood pressure can lead to dizziness.

Symptoms like a severe headache, dramatic changes to your vision, and sudden hormonal deficiencies should prompt an immediate medical evaluation. These can be symptoms of pituitary apoplexy, or sudden bleeding of a pituitary tumor. Early detection and treatment can prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Please note that the presence of these symptoms alone doesn’t mean you have a pituitary tumor. A thorough evaluation by a healthcare professional is required to make an accurate diagnosis.

Pituitary Tumor Diagnosis

Typically, a pituitary tumor is first suspected based on symptoms—though many asymptomatic, slow-growing, or symptomatically ambiguous tumors go undetected. Sometimes, doctors don’t diagnose pituitary tumors until routine blood or imaging tests are done for another reason.

Doctors use the following exams and imaging tests to diagnose pituitary tumors:

- Physical and neurological exam: First, your healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms, overall health, and family history. Next, they’ll complete an examination to assess neurological function, including reflexes, coordination, strength, and sensation.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Imaging studies are crucial in visualizing the brain and identifying abnormalities, and an MRI is a gold standard for pituitary tumors. An MRI provides detailed images of the pituitary gland and its surrounding structures.

- Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans rely on X-rays to create detailed cross-sectional images of the brain and are used in cases where an MRI is not feasible or an additional evaluation of the surrounding structures is needed.

- Testing: When it comes to pituitary tumors, specific tests are needed to assess pituitary function and assess hormone production, including:

- Prolactin: Elevated levels of prolactin can signal a prolactinoma.

- Growth hormone: Abnormal growth hormone levels (GH) can indicate a GH-secreting tumor.

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): This test can rule out or confirm Cushing’s disease.

- Thyroid hormones (TSH, T3, T4): This test will analyze certain thyroid hormones.

- Urine cortisol: This test measures excess cortisol levels over 24 hours.

- Genetic testing: Genetic testing is recommended if you have a family history of pituitary tumors or related endocrine disorders, if you’re 30 years of age or younger, or if you have tumors in multiple endocrine glands, including the pituitary gland. A blood sample is taken to extract DNA. Genetic testing benefits those with specific risk factors or family histories.

- Biopsy: During a biopsy, a small tumor sample is removed and sent to a pathology laboratory for analysis. There, pathologists examine the tissue under a microscope to determine the type of cells present, as well as other important characteristics that guide treatment decisions.

- Venous sampling: In complex cases, a procedure known as venous sampling takes a sample of blood from the veins coming out of the pituitary gland to measure hormone levels. This helps determine whether excessive hormone production originates from the pituitary gland or another source.

You may also be referred to an eye doctor or neuro-ophthalmologist for a vision test since pituitary tumors can damage optic nerves and cause vision problems.

After performing a combination of these tests and imaging, your care team will work with you to formulate a treatment plan.

Pituitary Tumor Treatments

Many pituitary tumors do not require treatment, meaning the first line of defense can be a “wait and see” approach with routine checkups and imaging. If your tumor does start to cause symptoms or threaten nearby areas of your brain, your doctor may suggest the following treatments.

Surgical Treatment

Neurosurgeons typically offer a surgical option when pituitary tumors cause hormonal imbalances or put pressure on nearby structures. The surgical strategy will depend on the tumor’s size, type, location, and impact on surrounding tissues.

- Transsphenoidal surgery: The most common surgical approach for a pituitary tumor is transsphenoidal surgery. This is when a neurosurgeon accesses and removes the tumor through the nasal passages and the sphenoid sinus using a small surgical instrument and an endoscope. Transsphenoidal surgery works best on small to medium-sized pituitary tumors confined to the sella turcica—the bony compartment of the pituitary gland—and leaves no scar. It also minimizes the risk of complications and offers a faster recovery.

- Craniotomy: Larger, more complicated pituitary tumors may require the surgical opening of your skull, known as a craniotomy. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon will make an incision in the scalp, remove a portion of the skull, and access the brain to remove the tumor, all while using intraoperative imaging and highly specialized tools to visualize and safely remove the tumor. This procedure is more invasive than transsphenoidal surgery. It requires a longer recovery time, but, fortunately, neurosurgeons can usually treat most pituitary tumors with less-invasive endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery.

Nonsurgical Treatments

Neuroendocrinologists might recommend the following nonsurgical treatments for pituitary tumors, on their own or in conjunction with surgery:

- Radiation Therapy: Doctors often use radiation when surgery is not an option or tumor removal is incomplete, and the tumor continues to grow or secrete hormones despite medication. Radiation therapy uses precisely aimed beams of radiation to destroy tumors in the body. While it doesn’t remove the tumor, radiation therapy damages the DNA of the tumor cells, which then lose their ability to reproduce and eventually die. This treatment is non-invasive, with no hospitalization required. However, its tumor-shrinking effects may take months or even years to develop.

- Radiosurgery: This nonsurgical treatment focuses beams of radiation on the site of the pituitary tumor while minimizing the radiation exposure of nearby structures. The two most common forms of radiosurgery are:

- Gamma Knife radiosurgery: This technique destroys abnormal tissue using precise and focused radiation beams and is only lethal to cells within the immediate vicinity. It’s an outpatient procedure that doesn’t involve incisions and requires brief sedation under a general anesthetic.

- CyberKnife radiosurgery: This technique uses targeted energy beams to destroy tumor tissue while sparing healthy tissue. It uses image-guided robotics to deliver surgically precise radiation to help destroy pituitary tumors. CyberKnife is also an outpatient procedure and does not require general anesthesia.

- Medication: Medications can help manage pituitary tumors by lowering the amount of hormones the body makes or even shrinking certain types of pituitary tumors. For prolactin-secreting tumors, medication can cause them to shrink while also blocking the hormone effects in the body. In the event hormones fall to unhealthy levels, your doctor will likely recommend hormone replacement therapy to help restore hormones to a healthy level. For tumors that cause Cushing’s disease and conditions like acromegaly or gigantism, surgery is preferred.

- Chemotherapy: Oncologists rely on chemotherapy to treat aggressive or malignant pituitary tumors that do not respond to other treatments, like pituitary carcinomas. Your doctor may give chemotherapy drugs orally or intravenously to inhibit the growth of cancer cells, sometimes in combination with surgery or radiation therapy. Fortunately, cancerous tumors of the pituitary gland are exceedingly rare.

- Watchful waiting: For pituitary tumors that don’t cause significant symptoms, your doctor may recommend regular monitoring instead of immediate treatment. To adequately monitor tumor growth, periodic MRI scans and hormone testing will be done to look for changes. However, if your tumor continues to grow after surgery or starts to cause symptoms, surgical or nonsurgical interventions may become necessary.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s renowned Pituitary Center, we treat people with pituitary tumors and disorders in one robust location. And because our doctors and nurses treat more people with pituitary disorders than any other team in the Southwestern U.S., you can rest assured that you’ll be in experienced hands.

Common Questions

How common are pituitary tumors?

Pituitary tumors are relatively common, though many are asymptomatic and therefore not diagnosed. Only about 1 in 1,000 to 4,000 people are diagnosed with a pituitary tumor that causes symptoms or requires treatment, including:

- Prolactinomas: These account for 40 to 50 percent of all pituitary tumors.

- Nonfunctional adenomas: These comprise between 25 and 35 percent of all pituitary tumors.

- ACTH-secreting tumors: These represent 10 to 15 percent of pituitary tumor cases and are responsible for Cushing’s disease.

Growth hormone-secreting tumors: These tumors happen in three to six percent of all cases, and lead to acromegaly in adults or gigantism in children.

Who gets pituitary tumors?

Doctors most commonly diagnose pituitary tumors in adults between the ages of 30 and 60. Pediatric pituitary tumors account for only a small percentage of cases. Still, when they do occur, they’re often associated with genetic syndromes.

Certain types of pituitary tumors, like prolactinomas, are more common in women, especially during pregnancy or in menopause. In other types of pituitary tumors, the gender distribution is more equal.

What is the prognosis for those with a pituitary tumor?

The prognosis for someone with a pituitary tumor is generally favorable. Still, it will depend on the type of pituitary tumor, its size, whether it produces hormones, and how early it’s diagnosed. Most pituitary tumors are slow-growing, noncancerous growths, and some don’t even require treatment.

The prognosis is generally good for functional pituitary tumors with appropriate treatment, although symptoms may take some time to resolve. For nonfunctional pituitary tumors, the outcomes are generally favorable if the tumor is discovered early and treated promptly.

Microadenomas, or pituitary tumors measuring less than 1 centimeter, tend to have an excellent prognosis with early detection and treatment. Macroadenomas, or pituitary tumors measuring more than 1 centimeter, tend to lead to nerve compression or tissue invasion, making treatment more complex.

For metastatic pituitary carcinomas, the prognosis can be less favorable, with the average survival after diagnosis ranging between one and three years. However, long-term survival is possible when the tumor is detected early and responds well to treatment.

If left untreated, pituitary tumors can lead to complications, such as vision loss, pituitary hormone deficiencies, hypopituitarism, or other systemic issues.

Can a pituitary tumor be prevented?

Currently, there is no known way to prevent pituitary tumors. Most develop sporadically, meaning they’re not inherited or linked to clear environmental or lifestyle factors. However, there are a few factors to keep in mind:

- Genetic counseling: Since some pituitary tumors are associated with inherited genetic conditions, genetic counseling and testing can help assess overall risk if you have a family history of these conditions.

- Screening and early detection: While pituitary tumor prevention isn’t possible, early detection can help minimize potential complications. Regular medical checkups are key, especially if you have a family history of these conditions. Call your doctor if you experience symptoms like persistent headaches, new vision problems, or unusual hormonal changes.

Resources

American Association of Neurological Surgeons