Pituitary Apoplexy

At a Glance

- Pituitary apoplexy is a serious medical condition that happens when blood flow to the pituitary gland decreases or uncontrolled bleeding near the gland compromises its function.

- The majority of cases happen in people with pituitary tumors that are often undiagnosed at the time of apoplexy.

- Symptoms can include a sudden and severe headache, often defined as “the worst headache of your life,” vision impairment, and a confused or fatigued mental state.

- Corticosteroids are the primary treatment, and doctors give them as soon as possible to support a critical hormone called cortisol.

Overview

Pituitary apoplexy occurs when there’s a hemorrhage or sudden loss of blood supply in the pituitary gland.

The pituitary gland is a small but critical gland at the base of the brain that controls essential hormones, such as:

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Growth hormone (GH)

- Prolactin

- Luteinizing hormone (LH)

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)

These hormones regulate a wide range of bodily functions.

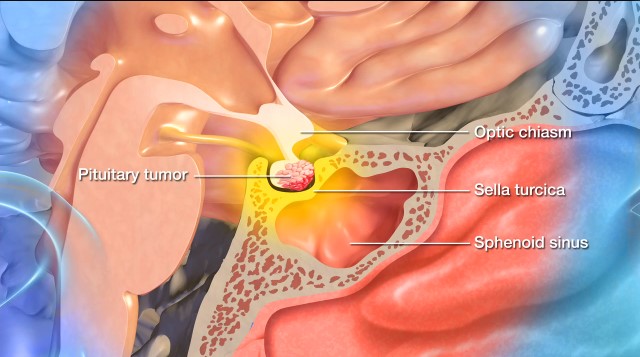

Pituitary apoplexy most often occurs in someone who already has a pituitary tumor, often without the person knowing about the tumor. The pituitary tumor may suddenly outgrow its blood supply or begin to bleed, which causes increased internal pressure and damage to the surrounding areas, like the optic nerves.

Pituitary apoplexy can have immediate and severe effects that, in most cases, require emergency medical treatment.

Did you know?

The word “apoplexy” comes from the Greek word “apoplexia,” which means “to be struck down.” In ancient times, it described those who suddenly collapsed and lost consciousness.

What causes pituitary apoplexy?

It’s not always clear why pituitary apoplexy happens. It’s most often the result of a tumor that becomes unstable, either by bleeding or losing its blood supply. Specific stressors or medical events can make this more likely, but sometimes, pituitary apoplexy happens without warning.

Known causes of pituitary apoplexy can include:

- Pituitary tumors: The majority of pituitary apoplexy cases happen in people with pre-existing pituitary tumors. These tumors, which are almost always benign, can outgrow their blood supply, especially if they’re large or rapidly growing.

- Sudden drop in blood flow: Anything that reduces blood flow to the pituitary gland can lead to tissue death and trigger apoplexy. This can happen during major surgery (especially heart or brain surgery), severe blood loss or trauma, shock or very low blood pressure, and childbirth, particularly if there’s heavy bleeding. This specific condition is known as Sheehan’s syndrome and is a form of postpartum pituitary apoplexy.

- Bleeding into the pituitary gland: Some events can increase the risk of bleeding into the tumor or pituitary gland, like the use of blood thinners, having a known bleeding disorder like hemophilia, undergoing radiation therapy to the pituitary gland or nearby areas of the brain, and experiencing head trauma (although pituitary apoplexy following head trauma is rare).

- Physical stress: Severe physical stress, such as intense exercise, a severe infection or fever, and straining while lifting heavy objects or during childbirth, can raise blood pressure or suddenly stimulate the pituitary, potentially triggering apoplexy.

- Pituitary stimulation: Certain medications or conditions that stimulate the pituitary gland can occasionally provoke apoplexy, such as GnRH agonists used in prostate cancer or fertility treatments, or dynamic endocrine testing that monitors how the pituitary gland responds to stimulation, like a hormone injection or a specific drug.

Pituitary Apoplexy Symptoms

The symptoms of pituitary apoplexy tend to come on suddenly and dramatically due to the rapid swelling or bleeding of the pituitary gland, which puts pressure on nearby structures and profoundly disrupts hormones.

If you or someone you know experiences pituitary apoplexy, you may encounter a combination of the following symptoms:

- A sudden, severe headache: Frequently described as the worst headache of your life, a sudden-onset headache is the most common symptom of pituitary apoplexy. It often starts abruptly, is felt near or behind the eyes, and is defined as intense and throbbing.

- Nausea and vomiting: These symptoms stem from a sudden rise in pressure inside the skull.

- Vision problems: Pituitary gland swelling or bleeding can compress the nearby optic nerves. This, in turn, can cause blurred or double vision, a loss of peripheral vision, difficulty moving the eyes that causes eye pain or drooping eyelids, and in severe cases, complete vision loss.

- Altered mental state: During pituitary apoplexy, you might feel confused, drowsy, or faint, especially if the brain isn’t getting enough cortisol due to hormonal failure. In extreme cases, you may lose consciousness or become comatose.

- Stiff neck or fever: Although this is a less common symptom, it can occur if the bleeding irritates the meninges, or the membranes around the brain. This particular symptom can mimic the symptoms of meningitis.

- Hormonal deficiencies: In cases of pituitary apoplexy, the pituitary gland cannot make enough hormones, which can then cause low blood pressure, low blood sugar, extreme fatigue or weakness, paleness, dizziness, and cold intolerance.

A sudden and severe headache, vision changes, and possible signs of hormone deficiency require immediate medical attention. If you are experiencing a combination of these three “red flag” symptoms, please call 9-1-1.

Pituitary Apoplexy Diagnosis

Diagnosing pituitary apoplexy involves recognizing the symptom pattern and undergoing brain imaging and blood tests to check hormone levels and assess pituitary gland functioning. Treatment often starts before full results are back to protect you or your loved one from adrenal crisis.

Doctors often use the following exams, tests, and imaging tests in the process of diagnosing pituitary apoplexy:

- Clinical suspicion: The diagnosis typically starts when you or your loved one comes to the emergency room with a sudden and severe headache, vision changes, and possible signs of hormonal crisis, like low blood pressure or confusion. Medical professionals may already suspect pituitary apoplexy, especially if there’s a known pituitary tumor.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Imaging studies are crucial in visualizing and identifying abnormalities within the brain—in fact, without proper imaging studies, it’s challenging to recognize pituitary apoplexy. An MRI is valuable for pituitary tumors and apoplexy because it can show bleeding in or around the pituitary gland, swelling or damage to the gland, and compression of nearby structures like the optic nerves.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: If an MRI isn’t available, your care team may order a CT scan of the head first. While CT scans can detect large bleeds faster, they may miss more minor or nonhemorrhagic apoplexy cases.

- Blood tests: These tests are crucial in determining which hormones are low. Standard blood tests include cortisol, which is often low in pituitary apoplexy and can be very dangerous, as well as ACTH, TSH, free T4, LH, FSH, prolactin, GH, electrolytes, glucose, and sodium to look for signs of adrenal insufficiency. Your doctor may also order a complete blood count (CBC) and coagulation tests can also be done if pituitary tumor bleeding is suspected.

- Endocrinology consult: An endocrinologist typically helps interpret the results and manage the hormonal crisis; especially when deciding on steroid replacement therapy, which can be urgent.

- Visual field testing: If vision problems are present, an ophthalmologist or neurologist may perform a visual field exam to assess how much of the visual field is affected.

Because this condition is considered a medical emergency, medical professionals should move quickly to confirm your diagnosis and begin treatment.

Pituitary Apoplexy Treatment

Even though it’s rare, pituitary apoplexy is a serious condition that needs prompt medical attention. The exact treatment will depend on how severe the symptoms are: for example, if you’re extremely sick or have vision loss, you may need emergency surgery to relieve pressure.

Corticosteroids are generally a frontline response and given as soon as possible because the pituitary gland may stop making critical hormones like cortisol during apoplexy.

Nonsurgical Treatments

In pituitary apoplexy, nonsurgical treatment begins immediately to help stabilize you or your loved one, even before imaging confirms the diagnosis.

- High-dose corticosteroids: This is the most critical initial treatment, administered intravenously, to replace lost cortisol, reduce brain swelling, prevent shock, and maintain blood pressure.

- Supportive care: Beyond corticosteroids, IV fluids, blood sugar, and low sodium or other electrolyte imbalances will be carefully monitored and addressed if they are not within normal ranges.

- Hormone replacement therapy: If blood tests show the pituitary isn’t making enough hormones, hormone replacement therapy is started, usually in consultation with an endocrinologist. Most pituitary apoplexy patients will require daily lifelong hormone therapy to help supplement or replace important pituitary gland hormones, like thyroid hormone, cortisol, desmopressin, which replaces vasopressin or antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and estrogen and progesterone for women or testosterone for men.

Follow-up appointments are also a critical part of your treatment plan, including regular endocrinology appointments for hormone monitoring, MRI scans to track your tumor size or possible tumor regrowth, and visual field exams to check for any residual vision loss.

Despite how serious pituitary apoplexy is, nonsurgical treatment can sometimes be enough—especially if your symptoms are mild and relatively stable.

Surgical Treatments

Generally, but not always, surgery for pituitary apoplexy is necessary when pressure on the optic nerves or brain causes vision loss or worsening consciousness.

The primary surgical treatment for pituitary apoplexy is transsphenoidal surgery. However, the exact surgical approach will depend on the tumor size, location, and the severity of your symptoms.

- Transsphenoidal surgery: This is the most common procedure used to treat pituitary apoplexy when surgery is required. In transsphenoidal surgery, a neurosurgeon removes the pituitary tumor through the nasal passages and the sphenoid sinus using a small surgical instrument and an endoscope or microscope for visibility and precision. The goal is to decompress the pituitary gland and surrounding structures, especially the optic chiasm, and remove any blood clot or tumor causing pressure. Transsphenoidal surgery is minimally invasive with a shorter recovery time and works best on small to medium-sized pituitary tumors.

- Craniotomy: Larger, more complex tumors may require the surgical opening of your skull, known as a craniotomy. During a craniotomy, a neurosurgeon will make an incision in the scalp, remove a portion of the skull, and access the brain to remove the pituitary tumor. This is done using intraoperative imaging and highly specialized tools to visualize and safely remove the tumor. A craniotomy is only used in select, more complex pituitary apoplexy cases. It is more invasive than transsphenoidal surgery, with a longer recovery time.

In patients with severe visual loss, deteriorating mental status, or a large mass, surgery is performed within 48 hours. In milder cases, surgery may be delayed or avoided if symptoms improve after initial treatment and careful monitoring. If a pituitary tumor is large, growing, or causing early symptoms, elective transsphenoidal surgery may be performed before apoplexy occurs.

With prompt medical care, many people who suffer from pituitary apoplexy recover well.

One Central Location with Multiple Treatment Options

At Barrow Neurological Institute’s renowned Pituitary Center, we treat people with pituitary tumors and disorders in one robust location. And because our doctors and nurses treat more people with pituitary disorders than any other team in the Southwest U.S., you can rest assured that you’ll be in very experienced hands.

Common Questions

How common is pituitary apoplexy?

Pituitary apoplexy is a rare condition, with an incidence of 0.17 episodes per 100,000 people each year. In other words, it affects approximately 1 out of every 590,000 people annually.

The condition is more likely in individuals who already have established pituitary tumors: between 2 and 12 percent of pituitary tumor patients may experience pituitary apoplexy. Doctors suspect that the incidence rate is even higher in pituitary tumors that don’t produce excess hormones, called nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas.

Despite being rare, the condition is considered an emergency due to its potential for hormonal collapse and vision loss.

Who gets pituitary apoplexy?

Most cases of pituitary apoplexy occur in adults between 40 and 60, although the condition can develop at any age. However, it is even more uncommon in children and young adults.

Some studies show a male predominance.

The following factors can increase your risk:

- Known or undiagnosed pituitary tumors

- Large pituitary tumors measuring greater than 10 mm

- The use of blood thinners such as warfarin or heparin

- Bleeding disorders

- Exposure to GnRH agonists, particularly in men with prostate cancer

- Recent major surgery or severe physical stress

- Pregnancy and childbirth, although rare, and often related to Sheehan’s syndrome

What is the prognosis for someone with pituitary apoplexy?

The prognosis for pituitary apoplexy is generally favorable. People recover well with proper and timely treatment, especially early steroid therapy and, if necessary, surgery. Vision outcomes and pituitary gland function after pituitary apoplexy will vary. Still, early treatment substantially improves the chances of vision recovery.

Up to 80 percent of patients will have some level of permanent pituitary hormone deficiency after apoplexy. Known as hypopituitarism, this means the pituitary gland is not producing one or more hormones in the quantities needed. Most individuals with hypopituitarism will require long-term hormone replacement therapy.

Complete recovery of pituitary function after apoplexy is possible, but it’s more likely in milder cases or if surgical treatments are performed. Vision recovery is generally good, especially if surgery is done early.

True recurrence of apoplexy is rare. Regular MRIs and endocrine follow-ups will be integral facets of long-term care. Pituitary apoplexy can be a life-threatening condition if not detected and treated, with a mortality rate that falls between 1.6 and 1.9 percent.

Can pituitary apoplexy be prevented?

You may not be able to prevent pituitary apoplexy. Still, some people can reduce their risk, especially those with a known pituitary tumor who undergo regular monitoring.

Many cases of pituitary apoplexy occur in people with undiagnosed pituitary tumors. If a tumor is found early—even incidentally on a scan done for something else—doctors can monitor it regularly, watch for growth or symptoms, and consider elective surgery if the tumor is compressing nearby structures. This proactive approach can prevent the tumor from reaching a size or stage where it might outgrow its blood supply or bleed.

Most pituitary apoplexy episodes occur suddenly and unpredictably, but understanding and managing risk factors can make a difference. People with pituitary tumors should be cautious if they have or need:

- Blood thinners: These anticoagulants increase bleeding risk, so their use requires careful consultation with your physician.

- Major surgery: A major surgery can trigger apoplexy. For patients who have known pituitary tumors, doctors will often give steroids during surgery to reduce the risk of apoplexy.

- GnRH agonist therapy: Used in prostate cancer or fertility treatments, this therapy can stimulate the pituitary and sometimes trigger apoplexy, especially if a pituitary tumor is present.

Some people experience a “warning headache” or mild vision changes before full-blown apoplexy. Seeking immediate care at the first signs can allow for early intervention and potentially prevent more severe complications.

For patients already diagnosed with a tumor, routine endocrine evaluations can identify hormonal imbalances before they become crises.