Enhancing Rostral Exposure for Carotid Endarterectomy: Technical Report

Authors

Karl A. Greene, MD, PhD*

Joseph M. Zabramski, MD

Robert F. Spetzler, MD

*Institute for Neurosciences and Division of Neurosurgery Conemaugh Memorial Medical Center, Johnstown, Pennsylvania

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Recent studies have demonstrated that carotid endarterectomy significantly reduces the risk of stroke in patients with high-grade stenosis of the carotid artery. Carotid surgery, however, is only beneficial in this group when it can be performed with a combined morbidity and mortality rate below 3% and 5% for asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, respectively. Meticulous technique, which includes adequate exposure of the internal carotid artery distal to the plaque, is key in minimizing the risks of this procedure. This report describes a simple and reliable technique of retracting soft tissue with fishhooks (Codman, Raynham, MA) attached to a Leyla bar (Aesculap, San Francisco, CA) to enhance rostral wound exposure during carotid endarterectomy. Exposure of the distal internal carotid artery is improved, particularly in patients with a high cervical bifurcation. The use of fishhook retraction improves rostral wound exposure during carotid endarterectomy. Soft tissue trauma is minimized, reducing the risk of paresis of the mandibular branch of the facial nerve associated with its compression at the angle of the jaw.

Key Words : carotid artery, endarterectomy, surgical technique

Endarterectomy of the extracranial carotid artery is an effective means of reducing the risk of stroke and death in both asymptomatic and symptomatic carotid artery occlusive disease for patients with 60% and 70% stenosis or greater, respectively.1-4 To achieve this beneficial effect, however, the procedure must be performed with minimal morbidity and mortality.1-5 Any surgical technique or method that contributes to the ease and safety of operative dissection and exposure of the carotid artery in the neck should increase the likelihood of uncomplicated and successful outcomes.

Technical issues in carotid endarterectomy have recently been reviewed.9 The presence of a high carotid bifurcation on preoperative imaging studies, for example, may be a significant risk factor for carotid endarterectomy.6 We describe a technique for enhancing rostral exposure of the internal carotid artery (ICA) during carotid endarterectomy. This technique exposes the relevant neurovascular structures in patients with a high cervical carotid bifurcation and eases removal of rostral plaque, placement of intraluminal shunts, and reapproximation of the arteriotomy.

Materials and Methods

Standard instruments used for operative dissection and exposure of the extracranial carotid artery at our institution include Debakey forceps, Metzenbaum and tenotomy scissors, a Shaw hemostatic electrocautery scalpel (Oximetrix, Inc.; Mountain View, CA), bipolar electrocautery forceps (Codman, Raynham, MA), and a pair of small Weitlaner (Codman, Raynham, MA) self-retaining retractors. Rostral exposure of the wound is enhanced when two to three fishhook retractors are attached to rubber bands with interposed strings (Codman, Raynham, MA) and a Leyla bar (Aesculap, San Francisco, CA). The latter instruments are usually reserved for self-retaining retraction of musculocutaneous flaps during craniotomies. A 9-French Microvac multiperforated suction tube (PNT, Inc.; Hopkins, MN) is also used during carotid arteriotomy, plaque dissection, and arteriotomy closure.7, 9 The combined use of these few instruments is sufficient to expose the ICA even in patients with a high cervical bifurcation.

Procedure

The details of microsurgical carotid endarterectomy as performed at our institution are described elsewhere.7, 9 Only those portions of the procedure relevant to rostral wound exposure are emphasized here.

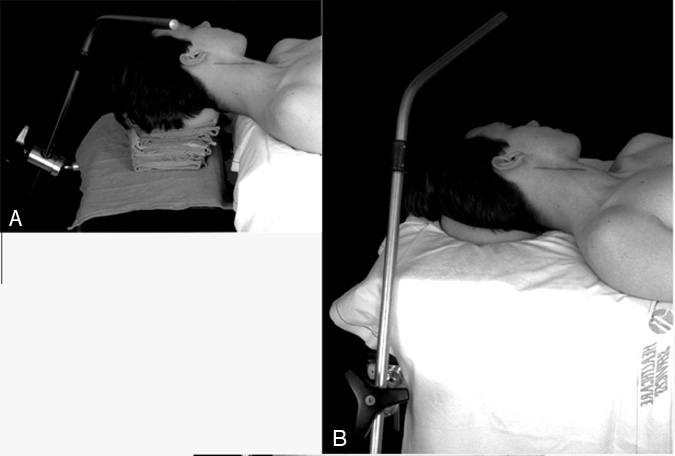

The patient is transferred to the operating room table and positioned to allow attachment of the Leyla bar holder (Fig. 1). The head is turned away from the side of the endarterectomy and extended slightly. The skin incision is outlined along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, beginning about 4 cm above the clavicle and extending rostrally to a point approximately one finger’s breadth lateral to the angle of the mandible (Fig. 1). Combined with the use of fishhook retractors (described below), this incision provides adequate exposure for most cases. When additional exposure is needed, the incision can readily be extended above the angle of the jaw to the level of the mastoid process.

After the skin is opened and the platysma muscle has been divided, small, blunt-tipped, self-retaining Weitlaner retractors are positioned at the superior and inferior margins of the wound and used to help expose the underlying soft tissue and vascular structures. The medial edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is dissected free and retracted laterally. The internal jugular and facial veins are identified next, and the facial vein is ligated and divided at its junction with the internal jugular vein. The carotid sheath is exposed by repositioning the lateral blades of the self-retaining retractors so that they displace the internal jugular vein laterally. Care is taken to keep the medial retractor blades superficial to the trachea, avoiding injury to the trachea and recurrent laryngeal nerve.

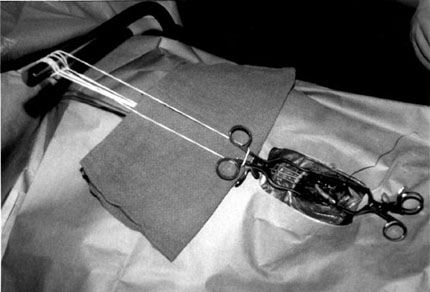

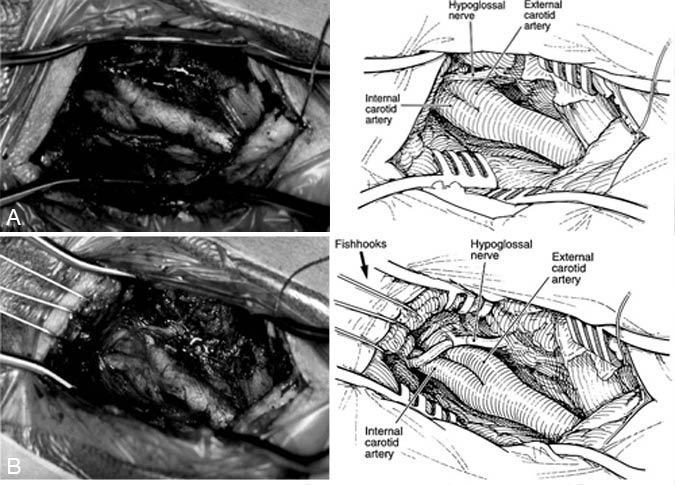

At this point in the procedure, a sterile Leyla bar is brought into the operative field and passed through the drapes at the side or head of the bed and fixed to its holder (Fig. 2). Two or three fishhooks are attached to the Leyla bar and then positioned one at a time in the soft tissues at the rostral end of the incision. One or more of the hooks can be used to elevate the digastric muscle. The strings interposed between the fishhooks and rubber bands are wrapped around the handles of the Weitlaner retractors to help prevent the retractor from shifting. Alternatively, a separate rubber band can be used to help hold the Weitlaner retractor in place (Fig. 2). With the hooks in place, the surgeon repositions the Leyla bar to maximize retraction. In addition to reducing the soft tissue trauma associated with retraction, the elevation of the soft tissues obtained by the fishhooks greatly enhances rostral exposure (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Exposure is the key to minimizing the risks associated with carotid endarterectomy. To quote Thoralf Sundt, “All too frequently complications related to this operation are directly attributable to a failure on the part of the surgeon to adequately expose the distal internal carotid artery.”8 Obtaining adequate exposure is further complicated by patients with a high-cervical carotid bifurcation and those with a short, thick neck. Since 1987 we have used this simple technique to enhance rostral exposure during carotid endarterectomy. The use of fishhooks both retracts and elevates the soft tissues overlying the distal ICA, creating a corridor for visualizing the artery up to the level of the lateral mass of the axis.

In all but a few cases, the operative incision need not extend above the angle of the jaw to expose the carotid bifurcation. Finally, because the fishhook retractors do not compress the soft tissues against the bony prominences of the mandible, the risk of trauma to the mandibular branch of the facial nerve (the most common cranial nerve injury in carotid endarterectomy) is minimized.

References

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group: MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial: Interim results for symptomatic patients with severe (70-99%) or with mild (0-29%) carotid stenosis [see comments]. Lancet 337:1235-1243, 1991

- Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study: Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis.JAMA 273:1421-1428, 1995

- Mayberg MR, Wilson SE, Yatsu F, et al: Carotid endarterectomy and prevention of cerebral ischemia in symptomatic carotid stenosis. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 309 Trialist Group [see comments]. JAMA 266:3289-3294, 1991

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators: Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 325:445-453, 1991

- Nussbaum ES, Heros RC, Erickson DL: Cost-effectiveness of carotid endarterectomy. Neurosurgery 38:237-244, 1996

- Spetzler RF, Bailes JE, Apostolides PJ: Rationale and protocol for microsurgical carotid endarterectomy, in Bailes JE, Spetzler RF (eds): Microsurgical Carotid Endarterectomy. Philadelphia/New York: Lippincott-Raven, 1996, pp 105-140

- Spetzler RF, Martin N, Hadley MN, et al: Microsurgical endarterectomy under barbiturate protection: A prospective study. J Neurosurg 65:63-73, 1986

- Sundt TM, Jr: General overview and principles of neurovascular surgery, in Apuzzo MLJ (ed): Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1993, pp 794

- Zabramski JM, Greene KA, Marciano FF, et al: Carotid endarterectomy, in Carter LP, Spetzler RF, Hamilton MG (eds):Neurovascular Surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994, pp 325-357