The Role of Psychotherapy in a Neurological Institute

George P. Prigatano, PhD

Kris A. Smith, MD†

Division of Neurology, †Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

In a neurological institute, the study and treatment of diseases of the central nervous system are of primary importance. In many instances, however, treatment is only partially successful. A good neurological recovery often does not mean that patients’ higher brain functions are completely normal. Helping patients cope emotionally with such residual disturbances can greatly enhance patients’ quality of life—this is the role of psychotherapy in a neurological institute.

Key Words: brain damage, psychotherapy, quality of life

Brain injuries can produce profound changes in persons’ sense of reality and self-perceptions.[2,5,6] Memory impairments, language disorders, difficulties initiating action, and problems in planning and judgment are just a few of the neuropsychological disturbances that can shatter individuals’ sense of self-confidence and produce considerable despair as they attempt to live with the consequences of a brain disorder.[7] Thus, helping patients to understand their neuropsychological deficits and to reconstruct their life in the face of (not despite) their personal suffering remains a central and vital activity of clinical neuropsychologists, particularly those working in a neurological setting.[7]

The role of psychotherapy in postacute brain injury rehabilitation of patients with severe traumatic brain injuries is well documented.[3,7,9] The needs of patients with focal brain injuries for psychotherapeutic interventions vary.[7] In a common scenario, patients undergo a successful neurosurgical procedure to treat a focal brain lesion and convince their neurosurgeon to release them to return to work. Many of these patients then encounter cognitive limitations that they did not anticipate and were not alerted to.[5,6]

The proper evaluation of higher cerebral dysfunction and, at times, the psychotherapeutic treatment of these individuals are important services for a neurological institute to offer. Expert neurosurgical and neurological care helps patients to avoid problems that threaten life itself. Once their life is preserved, however, patients may have residual neuropsychological deficits. Helping them to cope emotionally with such deficits is often crucial to their quality of life. The following case study, typical of patients encountered in a neurological center, is intended to alert neurological clinicians to issues that their patients often confront after medical and surgical treatment.

Illustrative Case

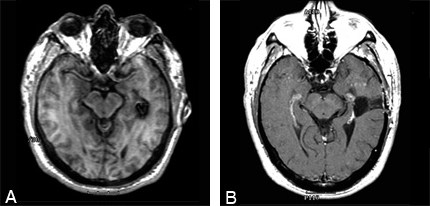

In July 1998, a 55-year-old, right-handed, Caucasian male developed an episode of numbness in his right finger, then his right toe, and then his lips. He was examined at a local emergency room but was discharged home. Later he was seen on an outpatient basis by a neurologist who further elicited that his episode included difficulty with his speech and vision. A magnetic resonance (MR) imaging study of the brain revealed a cavernous malformation in the left temporal lobe about 6 cm posterior to the temporal tip (Fig. 1A). Hemosiderin surrounding the lesion appeared hypodense on T2- and proton density-weighted images. On T1-weighted images, a small central hyperintensity suggested a small amount of subacute hemorrhage. Before the one episode of hemianesthesia and speech difficulty, the patient reportedly had been asymptomatic throughout his life.

Based on the MR imaging findings and symptoms, the patient was evaluated by a neurosurgeon. He reported that his difficulties with speech had resolved but that he had ongoing problems with headache, generalized fatigue, and symptoms of depression. His medical history was positive for hernia repair, bladder infection, lower back pain, and umbilical hernia surgery. His social history revealed no major difficulties. He did not smoke and used alcohol sparingly. His family history was unremarkable except that his mother had experienced a cerebrovascular accident.

Physical Examination

On examination, the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15. His cranial nerve and extraocular muscle function were intact. His tongue protruded midline and his face was symmetrical. His pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light, and his visual fields were full to confrontation. His motor strength was 5/5 throughout, and his reflexes were slightly hyperreflexic on the right side (3/4) compared to the left (2/4). He had no pronator drift. Pinprick sensation was decreased in the right upper and lower extremities and in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve. He exhibited no dysmetria, and his gait was normal.

The patient was considered to have had an acute hemorrage from the cavernous malformation which manifested in a complex partial seizure and headaches. He was not considered an appropriate candidate for gamma knife radiosurgery due to the lack of evidence that gamma knife protects against hemorrhage from cavernous malformations. He was offered a treatment course of anticonvulsants and observation with serial MR imaging; however, he chose to undergo a transsulcal approach to remove the cavernous malformation (Fig. 1B). Surgery was recommended to eliminate the risk of future hemorrage and to prevent chronic epilepsy. After surgery, he developed a partial left upper quadrant hemianopsia. Postoperative evaluation of his mental status indicated no obvious higher-order disturbances involving language or memory. He may have experienced a brief simple partial seizure shortly after surgery; however, he has been seizure free and off medication for 2 years.

Patient’s Subjective Report

After his successful surgery, this patient, who had always been a diligent worker, pressed his neurosurgeon to release him to return to his military position. Like many patients, he felt that returning to work would be “good therapy” for him. He enjoyed his work and the camaraderie of his fellow workers. Once at work, however, he experienced unanticipated difficulties. When he first read familiar documents, he could not understand them. He had trouble following what people were saying, particularly conversations involving small groups. Increasingly, he felt fatigued. He noted that his reading was slow and felt that it was most likely related to his right visual field loss. Secretly, he began to worry that he was going “crazy” because it was difficult for him to understand what people were saying to him. Although previously he had been articulate, both writing and speaking, he now found it difficult to formulate statements and to understand what others were saying to him.

Even though his coworkers and supervisors did not question his competency at work, they were aware that his performance was declining. The patient, greatly distressed and confused, saw his neurosurgeon at a follow-up examination and was referred for a neuropsychological examination to evaluate his higher cerebral functioning and to obtain recommendations for his care.

Objective Neuropsychological Test Findings

This patient underwent an extensive neuropsychological examination, of which the most prominent findings are summarized. His performance on the BNI Screen for Higher Cerebral Functions (BNIS) 6 months after surgery indicated that he had a subtle language impairment but not frank aphasia. The patient’s speech was fluent and he showed no paraphasic errors, but he had definite difficulties with auditory comprehension and naming. His verbal responses to a number of questions were slow. He could repeat and read simple sentences but felt that his spelling and writing had declined in a way that could not be measured easily. He noted considerable difficulty following conversations: When people spoke fast, he felt that they were literally “speaking another language.”

He was oriented to time and place and showed no evidence of a true dyscalculia. However, he had problems doing mental arithmetic, which had not been the case previously.

He had subtle difficulties with visual attention and visuospatial problem solving but notable impairments in memory. He could recall none of three words with distraction and only two of four items on the number/symbol/ association task. His total score on the BNIS was 38 of 50 points, producing a t score of 30 (two standard deviations below the mean for his age range).

Measures of intellectual functioning showed evidence of a decline in his problem-solving ability. On the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III, his Verbal Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was 98 and his Performance IQ was 97, yielding a Full Scale IQ of 98 (Table 1). His Vocabulary and Block Design subtest scores suggested that his premorbid IQ was most likely 110 to 120. A decline in his intellectual problem-solving skills, which are heavily dependent on concentration and speed of new learning, seemed likely.

Measures of intellectual functioning showed evidence of a decline in his problem-solving ability. On the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III, his Verbal Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was 98 and his Performance IQ was 97, yielding a Full Scale IQ of 98 (Table 1). His Vocabulary and Block Design subtest scores suggested that his premorbid IQ was most likely 110 to 120. A decline in his intellectual problem-solving skills, which are heavily dependent on concentration and speed of new learning, seemed likely.

Further tests of memory function revealed considerable problems with both verbal and nonverbal recall. On the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Form, his recall of short stories was at the 40th percentile for immediate recall and fell to the 29th percentile for delayed recall. His immediate recall of visuospatial information was at the 33rd percentile and at the 29th percentile for delayed recall. On the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test the total number of words that he recalled was substantially lower than normal. After five repetitions, he could only recall 8 of 15 words. Twenty minutes later, he could recall 5 words and made one error of intrusion. These findings documented unequivocal and severe memory impairment in an individual who appeared normal on gross neurological examination.

The findings of his neuropsychological examination confirmed his subjective report of difficulties with higher-order language and memory and indicate that he had returned to work prematurely.

Psychotherapy When Focal Neuropsychological Deficits Are Present

The process of psychotherapy is a highly individualized experience. Yet, recurring issues or themes related to psychological adjustment after brain injury have been noted.[3-8] Table 2 lists statements that the patient made throughout the course of his psychotherapy. Each comment reflects common issues that clinical neuropsychologists confront when attempting to conduct psychotherapy with brain dysfunctional patients who have focal neuropsychological deficits associated with various brain lesions.

The process of psychotherapy is a highly individualized experience. Yet, recurring issues or themes related to psychological adjustment after brain injury have been noted.[3-8] Table 2 lists statements that the patient made throughout the course of his psychotherapy. Each comment reflects common issues that clinical neuropsychologists confront when attempting to conduct psychotherapy with brain dysfunctional patients who have focal neuropsychological deficits associated with various brain lesions.

During an early psychotherapeutic interview, for example, the patient stated that “he thought he was going crazy” until he had undergone the comprehensive neuropsychological examination and received feedback about the nature of his deficits. Many patients with left-hemisphere lesions, particularly those affecting the temporal lobe, note that they have problems sustaining the thought process and find it hard to understand what people are saying but do not know why.

As discussed elsewhere,[7,10] disorders of awareness are common after brain injury, particularly in the early stages, but poorly understood. As we have asked many patients, “When the kidney is hurt, it tells the brain, but when the brain is hurt, who does it tell?” The reasons underlying such higher cognitive deficits may be obvious to neurosurgeons, neuropsychologists, and neurologists, but they are not obvious to patients. It is extremely important, therefore, to explain the nature of their higher cerebral deficits to patients in an appropriate fashion. Such information can be quite consoling; without it, patients can become increasingly distressed. This phenomenological state must be taken seriously. Often the first stage in establishing a therapeutic alliance with brain-injured patients is to help them understand what is wrong so that they do not feel that they are going crazy or that their problems are atypical or unusual.

In the course of psychotherapy, patients tell their story as it relates not only to their neurological insult but to the entire fabric of their life. As they describe the course of their life and the emergence of their neurological illness, they gain perspective about the personal meaning of their brain injury. Literally, they report, as Table 2 indicates, that they feel “much better” once they know what is “going on.”

Individuals with a brain injury often feel that they are simply “whining” about their problems; however, most individuals with similar problems would likely react the same. It is extremely important to allow patients to experience their personal suffering and to discuss their resulting frustrations and sadness in the context of a professional psychotherapeutic relationship. This process helps them to feel less alone with their problem, and it can help them to learn how to talk about their experiences with others. Many brain dysfunctional patients do not know how to discuss their higher cerebral deficits with a spouse or extended family members. Then, to everyone’s bewilderment, they make decisions that result in their social isolation and withdrawal.[7]

This patient’s difficulty with following conversations, particularly when several people were involved, illustrates this point. He also found noise extremely distressful, another common sequela of temporal lobe lesions. Repeatedly, the patient was uncomfortable in crowds and felt insecure when talking to small groups. He therefore tended to avoid these situations, which perplexed his spouse. Once she understood the nature of his higher-order language difficulties, however, his behavior became much more comprehensible. Both took steps to reduce the frequency with which they were in large groups. Furthermore, his wife could explain to others the difficulty that he had following group conversations. The ability of patients to understand their particular symptoms is an important factor in achieving successful psychotherapeutic interventions after focal brain lesions.

Another common characteristic of brain dysfunctional patients is that they do not anticipate that they will have trouble functioning in areas at which they were proficient before their surgery or injury. For example, this patient stated (Table 2), “I can’t believe how much trouble I have in doing simple jobs around the home.” As he better understood that the basis of some of his linguistic difficulties was his underlying problem with sequencing information, he began to realize why he found simple carpentry and home maintenance activities so difficult compared to the past. Without such knowledge, many patients feel totally incompetent and withdraw into a significant depression. Understanding his difficulty allowed the patient to pace himself and to limit the amount of work that he did each day. As a result, he became more successful. Such self-imposed modifications of behavior help ameliorate the problem of reduced self-esteem but do not eliminate it entirely. This patient’s understanding of his capacities is not false—he struggles daily with his reduced level of competency.

It is important to help patients to accept the support offered by others but also to give in return. This patient lamented that he did nothing for his wife and that she took care of him. He agreed to use a memory notebook system to compensate for his memory failures and began to list household chores that he could do that would help relieve some of his wife’s responsibility. He was eager to do so but privately was concerned about the process of using a memory notebook. Like many patients, he did not understand how memory compensation techniques could make a difference. As other patients have found,[1] however, the comprehensive procedural memory retraining program proved quite helpful to this patient. He worked with an experienced occupational therapist to learn the memory compensation techniques and later noted its efficacy (Table 2). To the degree possible, teaching patients to compensate for residual neuropsychological impairments has always been the hallmark of successful neuropsychological rehabilitation.[7] Fortunately, this patient did not have to undergo a full day-treatment program to benefit from this type of intervention. He coped quite well with psychotherapeutic consultation and training for memory compensation.

The patient still struggles with not being the man that he was before injury and with having to retire early but has commented spontaneously that “It means a lot to me to come and talk with you” (Table 2). He often notes that he feels like he is “in a fog” and struggles because no one really understands what is wrong with him—that physically he appears fine but his family and friends cannot comprehend his disturbed neuropsychological status. In one instance, I helped the patient to prepare a brief speech and to organize his thoughts when discussing his problems with his coworkers. He appreciated the intervention because it helped him to compensate for his higher-order linguistic problems.

In the course of working with this patient, I also asked him to read the book, The Man with the Shattered World.[2] He readily identified with the primary author of this book, a patient treated by Luria who suffered a large gunshot wound to the left temporal parietal area during World War II. Luria’s patient’s problems with functions like language, arithmetic, memory, and concentration were more severe, but my patient still shared numerous difficulties (e.g., trouble following rapid speech or multiple speakers). He often felt that he was on the verge of a psychotic break until psychotherapeutic consultation helped him to understand the nature of his linguistic and memory difficulties. Although this patient continues to struggle with the long-term higher cognitive deficits associated with the hemorrhage and subsequent surgical removal of his left temporal cavernous malformation, he has retired and is living a productive life with his spouse. He continues to be seen in periodic psychotherapeutic consultation.

Recommendations for Neurological Clinicians

Neurological clinicians must remember that an absence of deficits on the neurological examination does not necessarily equate with an absence of neuropsychological impairments. Listening carefully to what patients say about their neuropsychologic symptoms is important in determining the need for a neuropsychological examination and consultation. Such patients seldom receive these services because they appear to be neurologically normal. Only when patients insist at a follow-up examination that they are having higher cerebral deficits are such referrals made, particularly if patients have had a “good outcome.” However, there is no such thing as a silent brain lesion—only quiet ones. Patients with a focal lesion often sense that something is wrong but cannot articulate their problem. Family members may or may not understand what is wrong but with time perceive that the patient has notable daily difficulties. Providing patients with not only neuropsychological consultation examinations but the possibility of psychotherapeutic interventions when necessary can be important to helping these individuals rebuild the quality of their life—and to help them maintain their existing levels of psychosocial functioning. The importance of documenting the patient’s neuropsychologic impairments and counseling them before allowing them to go back to work is discussed elsewhere.[6]

As described elsewhere,[7] psychotherapy can be one of the most valuable services to provide another human being or it can be a tremendous waste of time and financial resources. Much depends on the skill of psychotherapists and their particular ability to help patients with their neuropsychological impairments. If successful, psychotherapy can improve the quality of life after patients have received expert neurosurgical and neurological care. Thus, the practice of psychotherapy after brain injury remains a combination of art and science. In the context of a neurological institute where “good science” goes hand in hand with “good service,” it is important to remember that more than science is needed for the successful treatment of neurological patients.[7]

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the patient for allowing his story to be told and Susan Kime, OTR, for her expertise in training the patient to use memory compensation techniques.

References:

- Kime SK, Lamb DG, Wilson BG: Use of a comprehensive programme of external cueing to enhance procedural memory in a patient with dense amnesia. Brain Inj 10:17-25, 1996

- Luria AR: The Man with a Shattered World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972

- Prigatano GP: Disordered mind, wounded soul: The emerging role of psychotherapy in rehabilitation after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 6:1-10, 1991

- Prigatano GP: Individuality, lesion location, and psychotherapy after brain injury, in Christensen A-L, Uzzell B (eds): Brain Injury and Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: International Perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1994, pp 173-199

- Prigatano GP: 1994 Sheldon Berrol, MD, Senior Lectureship: The problem of lost normality after brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 10:87-95, 1995

- Prigatano GP: Preparing patients for possible neuropsychological consequences after brain surgery. BNI Quarterly 11(4):4-8, 1995

- Prigatano GP: Principles of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999

- Prigatano GP, Ben-Yishay Y: Psychotherapy and psychotherapeutic interventions in brain injury rehabilitation, in Rosenthal M (ed): Rehabilitation of the Adult and Child with Traumatic Brain Injury. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1999, pp 271-283

- Prigatano GP, Fordyce DJ, Zeiner HK, et al: Neuropsychological Rehabilitation After Brain Injury. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986

- Prigatano GP, Schacter DL: Awareness of Deficit After Brain Injury: Clinical and Theoretical Issues. New York: Oxford UniversityPress, 1991