An Unusual Foreign Body in the Brain

Authors

Giuseppe Lanzino, MD

G. Michael Lemole Jr., MD

Jeffrey S. Henn, MD

Joseph M. Zabramski, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Low-velocity “domestic” foreign bodies dislodged intracranially pose several management dilemmas related to the nature, size, shape, chemical composition, and location of the object. Most of the information on retained intracranial foreign bodies is from reports of penetrating injuries from war wounds or civilian high-speed missiles. This information does not necessarily apply to domestic foreign bodies. The management of an unusual intracranial foreign body and the considerations particular to domestic foreign bodies are briefly reviewed in this report.

Key Words: craniotomy, frameless stereotaxy, intracranial foreign body, penetrating head injury

The bony cranium protects the brain from injury caused by low-velocity “domestic” foreign bodies. Because their kinetic energy is low, such foreign bodies usually gain access to the cranial cavity through areas of naturally occurring communication such as the open cranial sutures of infants[2,3,6,7,15,18] or the thin bony walls of the orbital cavities.[11-13] The management of a low-velocity penetrating cranial injury by an unusual foreign body is described in the case presented below.

llustrative Case

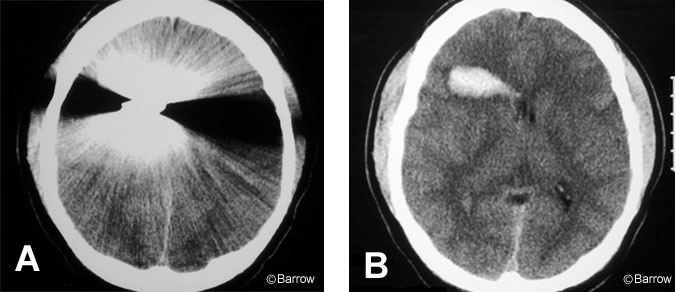

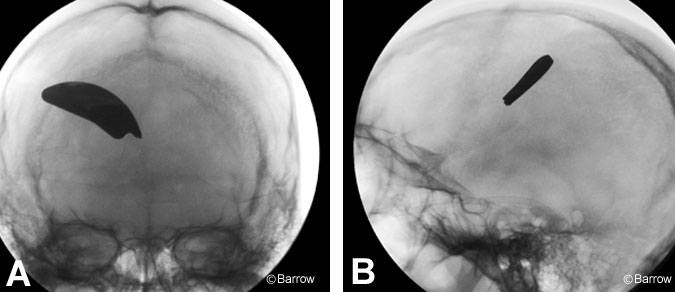

A 23-year-old male presented to our emergency room with a penetrating wound of the orbit, decreased level of consciousness, and left hemiparesis. He had been using a power edge trimmer, when one of the blades became detached, penetrated his right orbit, and lodged in the right frontal lobe (Figs. 1 and 2). A cerebral angiogram showed no evidence of vessel damage or pseudoaneurysm formation. The patient underwent a right frontal craniotomy. The metal blade (Fig. 3), which was not immediately apparent over the cortical mantle, was removed.

Guided with the aid of a computed tomography (CT)-based frameless stereotactic system, a small corticectomy was performed immediately overlying the metal blade (6×2 cm), which was about 1 cm deep from the cortical surface. Enucleation of the right eye was deemed necessary and was performed during a separate session. Postoperatively, the patient received broad-spectrum prophylactic antibiotics. Eventually, after a brief stay in a subacute rehabilitation facility, the patient made a full neurological recovery except for the loss of the right eye. Four months after surgery, follow-up CT (Fig. 4) showed a residual area of encephalomalacia.

Discussion

The management of retained foreign bodies is controversial. Most of the information available on this subject comes from reports of penetrating injuries from war wounds or civilian high-velocity projectiles.[1,10] In studies of war injuries, Cushing cautioned against the potential danger of aggressively removing a foreign body in patients with penetrating injuries.[9] Cushing’s conservative approach has been supported by studies from more recent armed conflicts on penetrating high-velocity missiles injuries.[8] On the basis of these studies, thorough debridement of the superficial wound tract without aggressive removal of a deeply located retained foreign body has been advocated.

The case described here posed a management dilemma because of its profound differences from penetrating wounds caused by high-speed velocity war or civilian missiles. The heat generated by a high-velocity bullet passing through tissues is thought to have a bactericidal effect that prevents or at least reduces the chances of contamination. In contrast, the foreign body that injured our patient was relatively low velocity and was contaminated by dirt and grass. These factors increased the risk of infection without proper cleansing. Other important considerations were the size and particularly the mass of the foreign body involved. Even small retained foreign bodies left untreated have been reported to move in the brain parenchyma or the ventricles in response to gravitational forces. Consequently, the danger of developing new or additional neurological deficits was present.[14,16,19,22] This risk of migration of the foreign body was particularly high in our patient because of its mass.

Chemical composition, shape, and location of the object are other factors worth considering when treating a patient with an intracranial foreign body retained from a domestic or work-related injury. Some metallic objects may decompose over time and release potentially toxic substances.[17,20] The removal of a complex, irregularly shaped foreign body is challenging because the surface of the object must be dissected from the surrounding brain tissue with care to avoid further trauma during extrication. In some cases, the presence of surrounding hematoma facilitates extrication by providing a soft cushion between the foreign body and the surrounding brain. Fortunately, this situation was true with our patient. When a sharp foreign body causes a penetrating injury, cerebral angiography is necessary to rule out the possibility of vessel damage with pseudoaneurysm formation or the presence of an arteriovenous fistula.[4] Our patient had no such injuries.

Small and deep-seated foreign bodies can be difficult to localize. In the past, frame-based stereotactic localization[21] or even a magnet[5] has been used to localize objects. The availability of frameless image-based systems has facilitated these efforts. These systems are invaluable in the case of intraparenchymal foreign bodies that do not reach the surface of the brain.

In our patient, the foreign body, which had entered the cranial cavity through the orbit, could not be visualized on the surface of the brain. There were no obvious signs on the cortical mantle (e.g., hemorrhage, discoloration, or localized bulge) to help determine the best trajectory to the blade. However, CT-based frameless localization helped identify the thinnest area of cortex overlying the blade so that the object could be removed successfully through a limited frontal corticectomy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, management of an unusual foreign body in the brain depends on the type, size, shape, and composition of the object to determine the optimal strategy for treatment. Frameless stereotactic systems greatly facilitate localization of deep-seated intraparenchymal foreign bodies not immediately visible on the surface of the brain.

References

- Aarabi B, Kaufman HH: Missile Wounds of the Head and Neck (vol. 1). Park Ridge, Illinois: American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 1999

- Abbassioun K, Ameli NO, Morshed AA: Intracranial sewing needles: Review of 13 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 42:1046-1049, 1979

- Ameli NO, Alimohammadi A: Attempted infanticide by insertion of sewing needles through fontanels. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 33:721-723, 1970

- Amirjamshisi A, Rahmat H, Abbassioun K: Traumatic aneurysms and arteriovenous fistulas of intracranial vessels associated with penetrating head injuries occurring during war: Principles and pitfalls in diagnosis and management. A survey of 31 cases and review of the literature. J Neurosurg 84:769-780, 1996

- Ashkenazi E, Mualem N, Umansky F: Successful removal of an intracranial needle by an ophthalmologic magnet: Case report. J Trauma 30:114-115, 1990

- Askenasy HM, Kosary IZ, Braham J: Sewing needles in the brain with delayed neurological manifestation. J Neurosurg 18:554-556, 1961

- Barlas O, Gokay H: Sewing needle injuries of the brain (letter). Neurosurgery 13:105-106, 1983

- Brandvold B, Levi L, Feinsod M, et al: Penetrating craniocerebral injuries in the Israeli involvement in the Lebanese conflict, 1982-1985. Analysis of a less aggressive surgical approach. J Neurosurg 72:15-21, 1990

- Cushing H: Notes on penetrating wounds of the brain. BMJ 298:221-226, 1918

- Grahm TW, Williams FC, Jr., Harrington T, et al: Civilian gunshot wounds to the head: A prospective study. Neurosurgery 27:696-700, 1990

- Greene KA, Dickman CA, Smith KA, et al: Self-inflicted orbital and intracranial injury with a retained foreign body, associated with psychotic depression: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 40:499-503, 1993

- Interligi M: Occupational cranio-cerebral wounds with foreign body retention. Chir Ital 29:577-585, 1977

- Lawson D, Glastonbury J, Oatey P: An unusual intracerebral foreign body associated with eye trauma. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 18:221-223, 1990

- Medina M, Melcarne A, Ettorre F, et al: Clinical and neuroradiological correlations in a patient with a wandering retained air gun pellet in the brain. Surg Neurol 38:441-444, 1992

- Muhammad AK, Maruno M, Maeda N, et al: Syringe needle located deep in the brain: Image-guided removal. Surg Neurol 54:458-464, 2000

- Notermans NC, Gooskens RH, Tulleken CA, et al: Cranial nerve palsy as a delayed complication of attempted infanticide by insertion of a stylet through the fontanel. Case report. J Neurosurg 72:818-820, 1990

- Ott K, Tarlov E, Crowell R, et al: Retained intracranial metallic foreign bodies. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg 44:80-83, 1976

- Rahimizadeh A, Sabouri-Daylami M, Tabatabi M, et al: Intracranial sewing needles (letter). Neurosurgery 20:666-666, 1987

- Rengachary SS, Carey M, Templer J: The sinking bullet. Neurosurgery 30:291-295, 1992

- Sherman IJ: Brass foreign body in the brain stem. A case report. J Neurosurg 17:483-485, 1960

- Sugita K, Doi T, Sato O, et al: Successful removal of intracranial air-gun bullet with stereotaxic apparatus. J Neurosurg 30:177-181, 1969

- Zafonte RD, Watanabe T, Mann NR: Moving bullet syndrome: A complication of penetrating head injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79:1469-1472, 1998