Stereotactic Brain Biopsy for Listeria Rhomboencephalitis in a Patient with Crohn’s Disease

Authors

G. Michael Lemole, Jr., MD*

Jeffrey S. Henn, MD**

Brian Fitzpatrick, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona

Current addresses:

*Department of Neurosurgery, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL

**Department of Neurosurgery, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Abstract

Listeria rhomboencephalitis is an extremely rare but well-described clinical entity. We present a 70-year-old man with Crohn’s disease with brain stem encephalitis caused by a Listeria infection. The diagnosis, which is usually made with blood or cerebrospinal fluid cultures and/or magnetic resonance imaging, was narrowed with stereotactic brain biopsy. Almost all cases of Listeria rhomboencephalitis have been reported in the neurology literature. Neurosurgeons, however, need to be familiar with this clinical entity so that its neurologic complications can be addressed rapidly. The key to treating this potentially devastating disease successfully involves early diagnosis and appropriate antibiotic therapy. A relationship between listerial antigens and Crohn’s disease has been described in the literature. This report, however, demonstrates the first case of listerial rhomboencephalitis in a patient with Crohn’s disease.

Key Words: Crohn’s disease, Listeria rhomboencephalitis, stereotactic biopsy

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular gram-positive bacteria. It is a well-known human pathogen with a proclivity for the central nervous system (CNS). It contributes significantly to the incidence of bacterial meningitis in the very young and very old. Although less often than meningitis, Listeria can cause devastating encephalitis or cerebritis. The organism has a particular trophism for the brain stem.[12,13,17]

As reported by Armstrong and Fung,[1] in 1957 Ecke described the first case of listerial rhomboencephalitis. Since then the disease has been correlated with the “circling disease of sheep.”[12] Although extremely rare, listerial rhomboencephalitis can be neurologically devastating. It is associated with a high rate of mortality even when treated promptly. Unlike patients with listerial meningitis, most patients with listerial rhomboencephalitis are not immunosuppressed. After a stereotypical prodrome, patients become symptomatic with cranial nerve palsies, long-tract or cerebellar signs, and progressive lethargy.

Most cases are diagnosed based on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging appearance and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood cultures. These studies, however, are not very sensitive. Early treatment with the correct antibiotic can almost double the rate of survival. Consequently, the condition must be diagnosed in a timely fashion and treatment must be initiated.[1,12,17] We describe a patient with rapid neurological decline in whom the diagnosis of Listeria rhomboencephalitis was aided by stereotactic brain biopsy. The relationship between listerial infection and preexisting Crohn’s disease is unclear. However, listerial antigens have been linked with the disease.[10]

Case Report

A 70-year-old man sought treatment after experiencing progressive weakness for 3 days. The weakness manifested as repeated stumbling and falling. The patient denied any syncopal episodes. He also described concurrent anorexia, cramping in the upper extremities, and a 102ºF fever.

The patient’s medical history was significant for Crohn’s disease with an active draining perianal fistula. He had been treated with Flagyl, but it was discontinued after he developed peripheral neuropathy. The patient’s current treatment for the Crohn’s disease included steroids and other immunosuppressants, including Asacol, Purinethol, and Remicade. He also had a history of several other gastroenterological disorders, including diverticulosis and diverticulitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and polyps in the colon. From a previous trauma, the patient’s left eye had been enucleated.

On initial physical examination, the patient appeared to be a well-nourished elderly male who was in no acute distress. His vital signs were unremarkable as was the remainder of his general examination. At admission, the patient was reported to have been grossly intact neurologically although his gait was not tested. He was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of his episodes of weakness and to optimize treatment of his Crohn’s disease.

His white blood cell count was 7x 103/ml, and his hemoglobin and hematocrit were 12.7 g/dl and 38.6%, respectively. His platelet count was 376x 103/ml and his erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 56 mm/hr. CSF obtained from a lumbar puncture revealed a peripheral white blood cell count of 229x 103/ml with 67% neutrophils and 14% lymphocytes. Initial gram stain and culture from the CSF were negative. Routine blood cultures also were obtained.

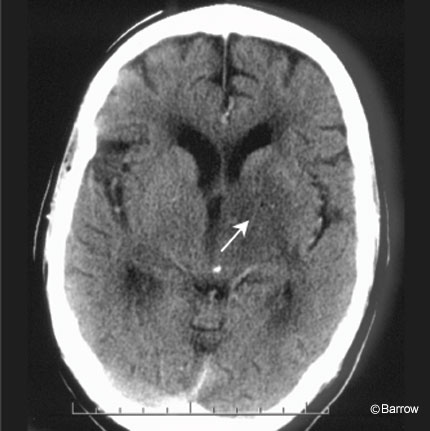

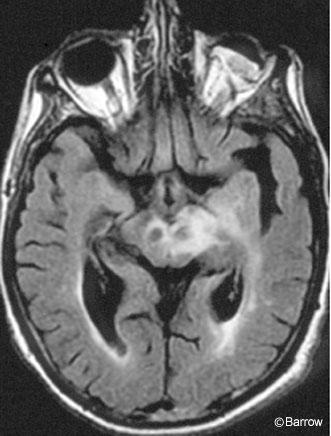

Enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head suggested some edema and subtle enhancement in the area of the left diencephalon down to the cerebral peduncle (Fig. 1). MR imaging of the brain showed a 3- to 4-mm enhancing lesion extending from the left internal capsule to the interpeduncular mesencephalon (Fig. 2). On T2- and intermediate-weighted images, diffuse brain edema extended from the left diencephalon down through the left middle cerebral peduncle into the midbrain (Fig. 3). No shift from mass effect or hydrocephalus was associated with these changes. The leading putative diagnosis was a primary neoplasm of the brain stem or an infection.

During the next 2 days, the patient’s neurological status deteriorated rapidly. He manifested right-sided hemiparesis, including a mild right facial nerve palsy. He became extremely somnolent to the point of barely following commands. Urgent neurological and neurosurgical consultations were obtained. Because the results of the patient’s blood and CSF cultures were not yet available, the decision was made to perform a CT-guided stereotactic biopsy of the left diencephalon for a definitive diagnosis.

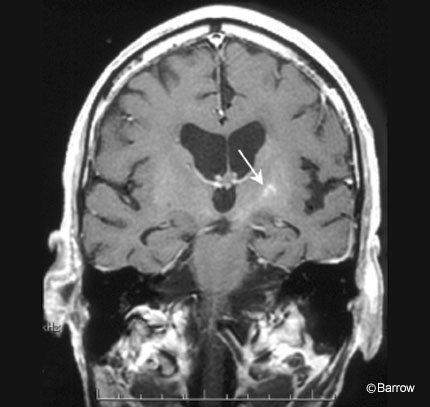

The patient was placed under local anesthesia and intravenous sedation. Preoperative planning and target selection were performed on the CT scanner computer. The Cosman-Roberts-Wells (CRW) frame (Radionics, Burlington, MA) was used for stereotactic guidance after the appropriate trajectory and target points were chosen in the diencephalon (Fig. 4). A small burr hole was made in the skull approximately at Kocher’s point on the left, and the biopsy needle was passed through the CRW frame to the target site where several tissue samples were obtained.

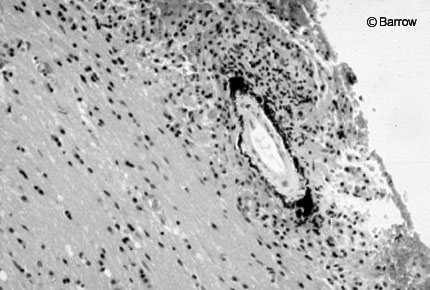

Frozen pathology suggested necrotic material and cellular debris, and a gram stain revealed no organisms (Fig. 5). These findings suggested infection rather than neoplasm, and the patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics. The next day, both the blood and biopsy cultures obtained the day before surgery grew gram-positive bacillus. The likely pathogen was believed to be Listeria monocytogenes, and the patient’s antibiotic regimen was changed accordingly to high-dose ampicillin and gentamicin.

Immediately after surgery, the patient continued to have right-sided paresis and subtle cognitive deficits. Four months later, he had recovered significant cognitive function and was able to ambulate independently at home. He still complained of incoordination on the right side. A physical examination revealed no focal weakness or cognitive deficits. Follow-up MR imaging showed that the lesion was resolving (Fig. 6).

Discussion

In 1993 Armstrong and Fung[1] reviewed the world literature for cases of rhomboencephalitis caused by Listeria monocytogenes. Sixty-three cases met the meta-analysis review criteria. In general a prodrome of headache, nausea, vomiting, and fever for several days preceded more severe symptoms, including asymmetric cranial nerve palsies, cerebellar dysfunction, and hemiparesis. Impaired consciousness usually followed. Peripheral white blood counts were only mildly elevated in most cases. CT scans could even be normal in some cases, and MR imaging typically delineated the lesions best. Significantly, CSF cultures were positive in only 41% of the reviewed cases and blood cultures were positive in 61%. Otherwise, the diagnosis was made at autopsy, or patients were treated presumptively based on MR imaging findings and clinical presentation. The mortality rate for untreated patients was almost 100%, 76% for patients initially treated with the wrong antibiotic regimen, and 40% for patients treated promptly with the appropriate antibiotics including ampicillin or penicillin.

Although CSF and blood cultures in our patient ultimately revealed the listerial infection, rapid neurologic deterioration and the need for a definitive diagnosis prompted surgical intervention with a stereotactic brain biopsy. The patient’s lesion extended in the midbrain, but the diencephalic focus provided an excellent target for biopsy. Even in the absence of such a thalamic lesion, stereotactic and open brain stem biopsies may be performed safely for a variety of pathologies, including infection, abscess, hematoma, and vasospasm.[2-4,7-9,15,16] None of the cases in Armstrong’s and Fung’s meta-analysis were diagnosed in this manner.[1] Brain stem abscess treatment with sterotactic aspiration has been described.[6,14] Optimal medical treatment with antibiotics can also be used for cases of frank listerial abscess. Still the neurosurgeon must consider diagnostic surgical intervention for a rapidly deteriorating patient with a ring-enhancing brain stem lesion and no definitive diagnosis. As our case illustrated, prompt institution of a broad-spectrum antibiotic regimen contributed to a significant neurologic recovery; the biopsy results strongly suggested an infection and ruled out a neoplasm. One must wonder how many patients with negative CSF and blood cultures are only diagnosed after autopsy.

These findings emphasize the need for prompt and accurate diagnosis of Listeria rhomboencephalitis. The differential diagnosis for encephalitis of this type includes vascular insults, neoplasms, autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis and neurosarcoidosis, central pontine myelinolysis, and infections.

In their extensive review of the literature, Armstrong and Fung[1] found that of 63 patients with listerial rhomboencephalitis only five were associated with immunosuppression: 1 transplant patient, 1 patient with rheumatoid arthritis, 1 patient with periarteritis nodosa, and 2 patients with sarcoidosis. In contrast, patients with listerial meningitis are often described as immunosuppressed. Interestingly, our patient was being treated for chronic Crohn’s disease with a typical immunosuppressive regimen.

To our knowledge, this case represents the first reported association between listerial rhomboencephalitis and Crohn’s disease. Listeriosis with meningitis and encephalitis has been associated with one other gastroenterologic comorbidity. In 1991 Lorber[11] described a case of listeriosis that followed shigellosis. Immunocytological evidence of Listeria antigens has been reported in association with Crohn’s disease,[5] but the relationship between these two entities, if any, is unclear.

Conclusion

This case illustrates a role for stereotactic brain biopsy in the diagnosis of listerial rhomboencephalitis. Although biopsies of the brain stem and diencephalon should be undertaken with some trepidation, our patient’s rapid clinical decline necessitated urgent action and immediate diagnosis. Most cases of Listeria rhomboencephalitis have been reported in neurology journals. However, it is important for neurosurgeons to understand this clinical entity to assist with prompt diagnosis and treatment and to identify when neurosurgical intervention is warranted.

References

- Armstrong RW, Fung PC: Brainstem encephalitis (rhombencephalitis) due to Listeria monocytogenes: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 16:689-702, 1993

- Baghai P, Vries JK, Bechtel PC: Retromastoid approach for biopsy of brain stem tumors. Neurosurgery 10:574-579, 1982

- Beatty RM, Zervas NT: Stereotactic aspiration of a brain stem hematoma. Neurosurgery 13: 204-207, 1983

- Chhang WH, Kak VK, Banerjee AK, et al: Stereotaxic biopsy of brain-stem tumours in children. Child’s Nerv Syst 6:409-411, 1990

- Chiba M, Fukushima T, Inoue S, et al: Listeria monocytogenese in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 33:430-434, 1998

- Fujino H, Kobayashi T, Goto I, et al: Cure of a man with solitary abscess of the brain-stem. J Neurol 237:265-266, 1990

- Kratimenos GP, Nouby RM, Bradford R, et al: Image directed stereotactic surgery for brain stem lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 116:164-170, 1992

- Kratimenos GP, Thomas DGT: The role of image-directed biopsy in the diagnosis and management of brainstem lesions. Br J Neurosurg 7:155-164, 1993

- Lath R, Rajshekhar V: Solitary cysticercus granuloma of the brainstem. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg 89:1047-1051, 1998

- Liu Y, Van Kruiningen J, West AB, et al: Immunocytochemical evidence of Listeria, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus antigens in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 108:1396-1404, 1995

- Lorber B: Listeriosis following shigellosis. Rev Infect Dis 13:865-866, 1991

- Lorber B: Listeriosis. Clin Infect Dis 24:1-11, 1997

- Mylonakis E, Hohmann EL, Calderwood SB: Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes: 33 years’ experience at a general hospital and review of 776 episodes from the literature. Medicine 77:313-336, 1998

- Rajshekhar V, Chandy MJ: Successful stereotactic management of a large cardiogenic brain stem abscess. Neurosurgery 34:368-371, 1994

- Rajshekhar V, Chandy MJ: Computerized tomography-guided stereotactic surgery for brainstem masses: A risk-benefit analysis in 71 patients. J Neurosurg 82:976-981, 1995

- Reigel DH, Scarff TB, Woodford JE: Biopsy of pediatric brain stem tumors. Child’s Brain 5:329-340, 1979

- Southwick FS, Purich DL: Intracellular pathogenesis of listeriosis. N Engl J Med 334:770-776, 1996