Surgical Treatment of Epidural and Transforaminal Spinal Meningiomas

Vivek R. Deshmukh, MD

Jonathan S. Hott, MD*

Curtis A. Dickman, MD

Division of Neurological Surgery, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona *Current Address: Private Practice, Phoenix, Arizona

Abstract

Purely extradural spinal meningiomas or dumbbell-shaped meningiomas pose unique surgical challenges. The medical records of one man and two women with histologically proven intradural-extradural or purely extradural meningiomas were reviewed. One patient presented with radicular symptoms and two patients presented with myelopathy. There was one cervical, one thoracic, and one cervicothoracic meningioma. All patients underwent a posterior approach. Two patients required nerve root sacrifice for resection of their tumor. All required dural reconstruction to prevent CSF leakage. One patient required an anterior cervical approach for stabilization. Postoperatively, all patients improved neurologically (mean follow up, 7 months). In one patient, residual tumor was treated with radiosurgery. One patient required reoperation for recurrent tumor. One patient underwent gross total resection and has shown no radiographic or clinical evidence of recurrence. Residual tumors should be followed closely, and surgical or radiosurgical treatment should be reserved for recurrent lesions.

Key Words: Extradural, intradural, meningioma, spine, surgical treatment, tumor

Abbreviations used: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MR, magnetic resonance

Cushing and Eisenhardt described the removal of a spinal meningioma as “one of the most gratifying of all operative procedures.”[4] Spinal meningiomas compose 20 to 45% of all primary spinal tumors in adults. They usually occur in the thoracic spine and frequently afflict females. Most of these tumors are located in the intradural compartment; 2 to 15% have an extradural component.[2,8] The natural history, treatment outcome, and recurrence rates of intradural spinal meningiomas have been described extensively.[9,10,12,15] Intradural-extradural and purely extradural spinal meningiomas, however, are exceptionally rare. Only a few cases have been reported. We reviewed our cases of purely extradural meningiomas and those with an extradural component with regard to presenting features, clinical and radiographic outcomes, and unique surgical considerations.

Illustrative Cases

Case 1

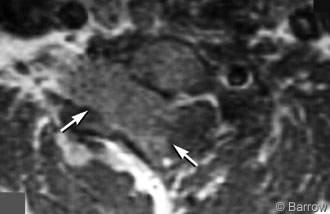

A 38-year-old man presented with numbness and weakness in his right hand and progressively worsening penmanship over 2 to 3 years. He developed neck pain about 4 months before evaluation. On neurological examination, the patient had numbness primarily in the C6 dermatome and trace weakness (4+/5) of the right wrist flexors, biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis muscles. On MR imaging, a 3.4 x 1.9 x 3.9 cm intraspinal mass associated with homogeneous contrast enhancement appeared to be intradural but extramedullary (Fig. 1). The tumor was eccentric to the right and associated with widening of the right C6 and C7 neural foramina. The thecal sac was displaced markedly to the left.

The patient underwent a C5 inferior laminectomy, complete C6 and C7 laminectomy, T1 superior laminectomy, and an aggressive right-sided facetectomy at C6-7 and C7-T1. The tumor was found to be both intradural and extradural. The C7 nerve root, which was infiltrated by tumor, was sacrificed to achieve gross total resection. Both the intradural and extradural segments were excised microsurgically. The dural pedicle from which the tumor arose was resected. Duraplasty was performed with interrupted 4-0 Nurolon suture and bovine pericardium. In the same setting, the patient underwent an anterior cervical discectomy, fusion, and plating from C5 to T1. Histological analysis revealed a psammomatous meningioma.

Postoperatively, the patient had a C7 nerve root deficit with triceps weakness (3+/5) and dysesthetic pain in the distribution of the C7 nerve root. At his last follow-up examination 1 year after surgery, his C7 radiculopathy had improved remarkably. His triceps strength was graded at 4+/5 and his dysesthesias had resolved. His neck pain, which had been debilitating before surgery, resolved as well. His 1-year follow-up MR imaging revealed no residual or recurrent tumor. Cervical spine flexion and extension films showed no instability.

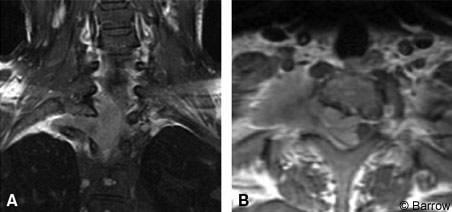

Case 2

A 29-year-old woman had a 3-month history of right lower extremity numbness and paresthesias as well as gait ataxia and dorsal column dysfunction. On examination, she exhibited evidence of myelopathy with 4+ deep tendon reflexes and 3-beat clonus. She had right lower extremity weakness graded at 4/5. On the right, sensation was diminished to light touch and pinprick. Her bowel and bladder function was intact. MR imaging showed a mass at C7-T1 eccentric to the right side associated with significant compromise of the spinal cord. The tumor extended through the right T1 neural foramen, which it widened, and into the apex of the thoracic cavity on the right side (Fig. 2).

The patient underwent C6-T2 laminectomies through a right C7-T1 costotransversectomy for exposure of the tumor. A retropleural thoracotomy was performed to fully resect the intrathoracic and extradural component of the lesion. The intra- and extradural portion of the tumor was excised microsurgically, and the involved dura was resected. The T1 nerve root was sacrificed. A duraplasty was performed with bovine pericardium. Histological analysis confirmed a meningothelial meningioma.

The patient underwent C6-T2 laminectomies through a right C7-T1 costotransversectomy for exposure of the tumor. A retropleural thoracotomy was performed to fully resect the intrathoracic and extradural component of the lesion. The intra- and extradural portion of the tumor was excised microsurgically, and the involved dura was resected. The T1 nerve root was sacrificed. A duraplasty was performed with bovine pericardium. Histological analysis confirmed a meningothelial meningioma.

Postoperatively, the patient developed right arm dysesthesias in the distribution of the C8 nerve root and intrinsic weakness of the right hand (4-/5). She also displayed a right Horner’s syndrome. After a routine recovery, she was discharged on postoperative Day 5. A 6-month follow-up MR imaging showed residual tumor (7.6 cc) ventral to the thecal sac, which was treated with Cyberknife radiosurgery. Her dysesthesias and intrinsic weakness of the right hand resolved, but her Horner’s syndrome persisted at her 1-year follow-up examination.

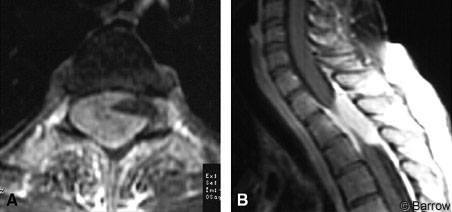

Case 3

A 35-year-old woman developed bilateral lower extremity numbness, weakness, gait ataxia, and myelopathy when she was 4 months pregnant. She underwent a therapeutic abortion for intrauterine fetal death. Her weakness worsened after surgery and independent ambulation became difficult. Bowel and bladder function was intact. On neurological examination, the patient exhibited lower extremity weakness (4/5), diminished pinprick and light touch sensation, increased lower extremity reflexes, clonus, and Babinski’s sign. Her gait was spastic. MR imaging showed an extradural mass at T1-T3 eccentric to the right associated with severe compression of the thecal sac (Fig. 3).

She underwent a T1 to T4 laminectomy with microsurgical excision of the epidural tumor. No nerve roots were sacrificed. Intradural exploration revealed no intradural tumor. The areas where the tumor attached to the dura were coagulated. She required no spinal fixation, and the dura was closed primarily without duraplasty or excision of the dura.

She underwent a T1 to T4 laminectomy with microsurgical excision of the epidural tumor. No nerve roots were sacrificed. Intradural exploration revealed no intradural tumor. The areas where the tumor attached to the dura were coagulated. She required no spinal fixation, and the dura was closed primarily without duraplasty or excision of the dura.

After 3 days in the hospital, the patient was discharged home neurologically intact. All preoperative deficits and the myelopathy had resolved. Immediate postoperative MR imaging verified gross total resection. Follow-up MR imaging 1 year later showed regrowth of tumor at T2-3 at the ventrolateral aspect of the thecal sac. The patient underwent a right costotransversectomy and bilateral transpedicular approach to the tumor. The T1-T3 nerve roots were sacrificed bilaterally so that the tumor could be resected completely. The dura to which the tumor was attached was also resected circumferentially. Fascia lata, bovine pericardium, and fibrin glue were used to complete the dural reconstruction. Postoperative MR imaging verified no residual tumor. After the second resection, she had mild spasticity and mild lower extremity weakness. She is now ambulatory with a walker (follow up, 1 month).

Discussion

Most intradural meningiomas can be resected with a laminectomy/laminoplasty and microsurgical excision of the lesion. Typically, there is no need to remove bone extensively. The area of dural attachment for an intradural meningioma can be treated with coagulation. However, if the dural attachments are accessible, a wide dural excision is preferred in any attempt to cure the tumor. Few of these cases require nerve root sacrifice. Spinal fixation after surgery is also uncommon. Surgical resection cures these lesions, and large surgical series have verified excellent outcomes.[9,11,18] Our three patients, however, show that meningiomas with an extradural component require a more complex surgical strategy.

Several cases of purely extradural meningiomas have been reported.[1,5,6,16] These tumors are thought to arise from remnants of the arachnoid cap cell at the exiting nerve root sheath3 or from arachnoid villi located along the nerve root sleeve.[7] Purely extradural meningiomas pose a diagnostic dilemma. Our patient with the extradural meningioma was pregnant. When she was diagnosed preoperatively, her differential diagnosis included choriocarcinoma or other metastatic lesion. The most common extradural tumor is metastasis, and this diagnosis is associated with a far worse prognosis than meningioma. Surgical excision is therefore crucial to establish a tissue diagnosis, to reduce the tumor burden, and to decompress the thecal sac. Similar to dumbbell lesions, extensive bony removal, nerve root sacrifice, and dural reconstruction may be necessary as it was in Patient 3.

Levy et al.[13] proposed that extradural meningiomas are associated with a more rapid course than intradural meningiomas and a shorter time to diagnosis. They believe that extradural meningiomas are locally invasive, more vascular than their intradural counterparts, and associated with a higher recurrence rate. In contrast, Solero et al.[18] found that extradural lesions behaved in a benign fashion with regard to tumor recurrence, much like intradural meningiomas. Roux et al.[17] also found no correlation between extradural location and increased recurrence rate. The prognosis after appropriate surgical treatment of extradural meningiomas may therefore be more favorable than previously thought. The following discussion outlines our surgical principles for the resection of extradural and intraduralextradural meningiomas.

Exposure

Our experience indicates that extensive bony removal is required and can be guided by the eccentricity of the lesion. If the resection involves the cervical level, the involved segments may be destabilized by the laminectomy and aggressive facetectomy. Therefore, stabilization of these segments must be considered. If the resection involves the thoracic spine, extensive posterior bone can be removed with impunity because of the stabilizing capacity of the rib cage and anterior columns.

Nerve Root Sacrifice

We found that one or more nerve roots can be intimately involved with these tumors. If gross total resection is to be achieved, the involved nerve roots may need to be sacrificed, as occurred in all three of our patients. Only Patient 1, whose C7 nerve root was sacrificed, continues to have a noticeable nerve root deficit. At the cervical and first thoracic levels, care must be taken to preserve the nerve roots to avoid neurological deficits. However, these patients may already have minor preoperative deficits in the distribution of the involved nerve root, and dissecting the nerve root from the tumor is exceedingly difficult. When appropriate, we advocate selective sacrifice of the nerve root if the goal is to cure the patient of the tumor.

Dural Reconstruction

These tumors involve the dura extensively. The appropriate management of the dural attachment is controversial. Solero et al.[18] and others have found no correlation between extensive dural resection or coagulation and the rate of recurrence.[17,18] Stern et al.[19] and Messori et al.[14] contend that dural resection is essential to prevent tumor recurrence. Given the young age of these patients, we also recommend aggressive dural resection with subsequent patch duraplasty. Bovine pericardium can be sutured into the existing normal dura with multiple interrupted sequential 4-0 Nurolon sutures. Fibrin glue dural sealant can be applied to complete the duraplasty. A lumbar drain should be placed routinely for postoperative drainage to allow the dural reconstruction site to heal. All three of our patients required excision of a large dural segment and dural reconstruction; none developed a CSF leak.

Radiographic Outcome

We achieved gross total resection in two of our three patients. Despite gross total resection, one of the patients had a symptomatic recurrence of her tumor, perhaps because a complete dural excision was not performed. Furthermore, the patient population afflicted by this disease process is typically young or middle aged, and residual tumor has ample time for recurrent growth. These facts provide further impetus for performing a complete tumor resection with dural excision when possible.

Clinical Outcome

Patients with extradural meningiomas typically become symptomatic with nerve root deficits, myelopathy, and pain. As demonstrated by our experience, patients can expect most of their symptoms to resolve after aggressive surgical resection (mean follow up, 1 year). Symptoms and signs resolved completely in the two patients who presented with myelopathy and paraparesis. All patients described a significant improvement in their preoperative pain. No patient developed a CSF leak or a pseudomeningocele. No patient has shown evidence of instability.

Conclusion

Intradural-extradural and purely extradural meningiomas pose unique diagnostic and surgical challenges that distinguish them from typical spinal meningiomas. All such patients should undergo surgical resection to establish a diagnosis, to decompress involved neural structures, and to attempt a surgical cure. Surgery requires extensive bone removal and possible spinal fixation and complex dural reconstruction. Highly selective cases require sacrifice of the nerve root. With the appropriate management strategy, the surgical resection of these lesions can remain “gratifying” to surgeons and curative for patients.

References

- Achari G, Behari S, Mishra A, et al: Extradural meningioma en-plaque of the cervical cord. Neurol Res 22:351-353, 2000

- Black P, Nair S, Giannakopoulos G: Spinal epidural tumors, in Wilkins RH, Rengachary SS (eds): Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995, pp 1791-1803

- Calogero JA, Moossy J: Extradural spinal meningiomas. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg 37:442-447, 1972

- Cushing H, Eisenhardt L: Meningiomas. Their Classification, Regional Behaviour, Life History, and Surgical End Results. New York, NY: Hafner Publishing Company, Inc., 1962

- Di Rocco C, Iannelli A, Colosimo C, Jr: Spinal epidural meningiomas in childhood: A case report. J Neurosurg Sci 38:251-254, 1994

- Dusenbery D, Ducatman BS, Fetter TW: Extradural spinal meningioma presenting as a neck mass. Diagnosis by aspiration cytology. Arch Pathol Lab Med 111:483-485, 1987

- Gambardella G, Toscano S, Staropoli C, et al: Epidural spinal meningioma. Role of magnetic resonance in differential diagnosis. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 107:70-73, 1990

- Haft H, Shenkin HA: Spinal epidural meningioma: Case report. J Neurosurg 20:801-804, 1963

- Katz K, Reichenthal E, Israeli J: Surgical treatment of spinal meningiomas. Neurochirurgia (Stuttg) 24:21-22, 1981

- Klekamp J, Samii M: Surgical results for spinal meningiomas. Surg Neurol 52:552-562, 1999

- Kumar S, Kaza R, Maitra TK, et al: Extradural spinal meningioma arising from a nerve root. Case report. J Neurosurg 52:728-729, 1980

- Kunicki A, Maciejak A: Results of operative treatment in 154 cases of extramedullary meningiomas and neurinomas. Acta Med Pol 6:397-404, 1965

- Levy WJ, Jr., Bay J, Dohn D: Spinal cord meningioma. J Neurosurg 57:804-812, 1982

- Messori A, Rychlicki F, Salvolini U: Spinal epidural en-plaque meningioma with an unusual pattern of calcification in a 14-year-old girl: Case report and review of the literature. Neuroradiology 44:256-260, 2002

- Mirimanoff RO, Dosoretz DE, Linggood RM, et al: Meningioma: Analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg 62:18-24, 1985

- Rosencrantz M, Stattin S: Extradural meningiomas. Report of two cases. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 12:419-427, 1972

- Roux F-X, Nataf F, Pinaudeau M, et al: Intraspinal meningiomas: Review of 54 cases with discussion of poor prognosis factors and modern therapeutic management. Surg Neurol 46:458-464, 1996

- Solero CL, Fotnari M, Giombini S, et al: Spinal meningiomas: Review of 174 operated cases. Neurosurgery 25:153-160, 1989

- Stern J, Whelan MA, Correll JW: Spinal extradural meningiomas. Surg Neurol 14:155-159, 1980