ALS Patient Joins Neurodegeneration Lab as Volunteer

Clough has amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive neurological disease that causes degeneration of the nerve cells responsible for initiating and controlling voluntary muscle movements.

Since his diagnosis in April 2014, Clough has become an advocate for the ALS community. Now he is taking an active role in helping Barrow researchers learn more about this fatal disease.

Contributing to the Science

Clough joined Dr. Rita Sattler’s laboratory in September as a research volunteer. He doesn’t have a professional science background, but the self-described “Jack of all trades, master of none” hopes to free up time for the scientists by handling some of the more tedious but necessary work.

“Then they can use their energy and their efforts for stuff that their brains are designed to do,” he said.

Dr. Sattler and her team have a prestigious R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health, as well as funding from the ALS Association and the Muscular Dystrophy Association, to study what causes the death of nerve cells (also called neurons) in degenerative diseases like ALS. One way they do this is by reprogramming blood or skin cells from patients into neurons and their support cells. The researchers image these patient-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells using a confocal microscope to study changes in the form and structure of the cells caused by the disease, also called their morphology.

Providing Doug with the opportunity to personally contribute toward the scientific understanding of his disease is very unique, and we are thrilled to be able to do so.

Dr. Rita Sattler, Associate Professor, Neurobiology

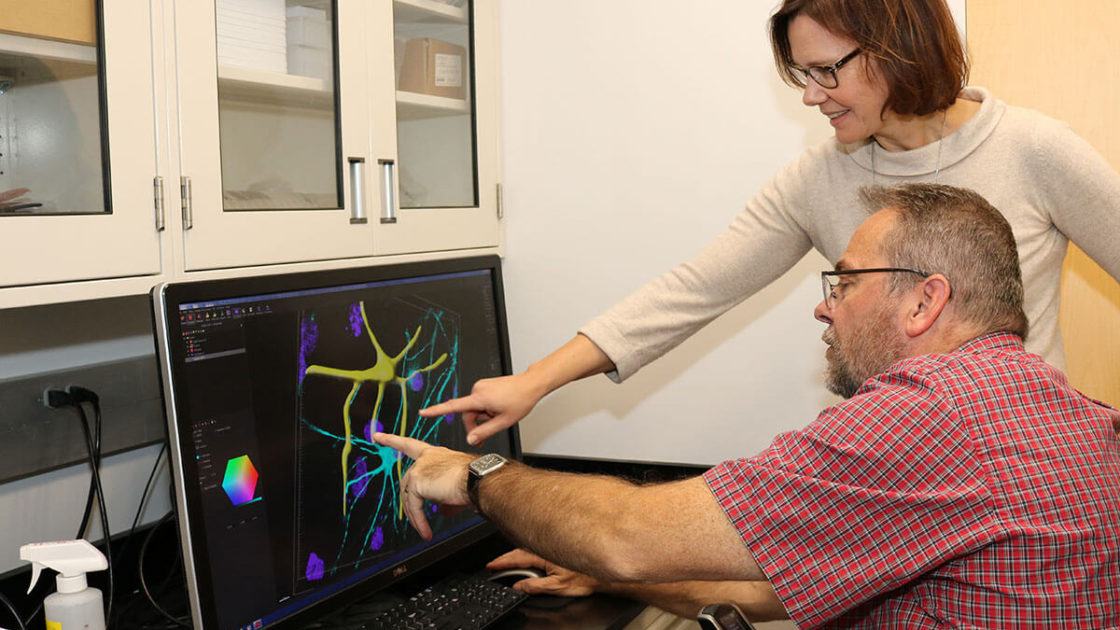

That’s where Clough comes in. He uses image-analysis software to trace the cells, which allows the researchers to quantify the morphological changes.

“Providing Doug with the opportunity to personally contribute toward the scientific understanding of his disease is very unique, and we are thrilled to be able to do so,” Dr. Sattler said. “At the same time, having Doug in the lab allows the members of the lab to learn how their hard work can have a direct impact on patients suffering from the disease they study.”

Clough said he is amazed by the number of researchers working toward a cure for ALS and calls them “unsung heroes.”

“We see a lot of people at the ALS Center—the breathing person, the social worker, the physical therapist, the nurse, the doctor—but we don’t see what’s going on behind the scenes,” he said.

A Voice for the ALS Community

Volunteering in the lab is just one of many ways Clough has been active in the fight against ALS.

He participates in a clinical trial as a patient of the Gregory W. Fulton ALS and Neuromuscular Disease Center at Barrow, he recruits family and friends to join him in the ALS Association’s annual Walk to Defeat ALS, he helped promote the latest Health & Wealth Raffle to benefit research at Barrow, and he is an ambassador for the Northeast ALS Consortium. He also spoke at a press conference Barrow held to announce a partnership with IBM Watson to use artificial intelligence to speed the process of identifying genes associated with ALS.

Speaking engagements and interviews have become regular occurrences for Clough. He can also hold an hour-long conversation with someone he just met and greets familiar faces with sarcastic jokes. So, it might surprise people to learn that he doesn’t actually love public speaking.

When Clough was asked to read Lou Gehrig’s famous farewell speech at an Arizona Diamondbacks game for the ALS Awareness Night, his wife, Karen, offered an important reminder.

“She said, ‘Your voice is still very strong, so when these opportunities come up, you shouldn’t say no,’ ” Clough recalled.

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, approximately 75 percent of people with ALS will develop weakness of the muscles that control speech.

Finding an Answer

For some people, a change in vocal pitch may be their first symptom of ALS. For others, like Clough, it may begin with weakness in a limb.

Clough brushed off the early signs of weakness in his left foot as just another back-related problem. He has had five back surgeries and lives with a chronic pain condition called adhesive arachnoidits. The condition is caused by injury to the arachnoid, a protective layer around the brain and spinal cord.

But when he began falling around his home and went from being able to ride his recumbent trike for up to 30 miles per day to feeling exhausted after a single mile, he decided he would mention it at his next doctor’s appointment.

The doctor said Clough’s history of back problems didn’t explain the new symptoms and referred Clough to a neurologist. After several tests including an MRI, blood work, electromyograms (EMG), and nerve conduction studies, the neurologist diagnosed Clough with ALS.

“I’m like, ‘OK, what is that?” ’ Clough recalled. “And she said, ‘That’s Lou Gehrig’s disease.’ And I said, ‘Oh, that’s not good, is it?’ I knew nothing. I knew that I had been at the game where Cal Ripken broke Lou Gehrig’s record in Baltimore. I knew Lou Gehrig died at an early age, but I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t even think it was an option.”

Approximately 6,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with ALS each year. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved a second drug for ALS that may help slow the decline in physical function, but the disease has no known cure.

The life expectancy of a person with ALS averages about two to five years from the time of diagnosis. However, the rate of progression is highly variable. According to the ALS Association, about 20 percent of people with ALS live five years after diagnosis, 10 percent live 10 years, and 5 percent live 20 years or more. Most people with ALS die of respiratory failure once it affects the breathing muscles.

Like most cases, Clough’s is sporadic. This means he has no family history of the disease. The inherited form of ALS, called familial ALS, only represents about 10 percent of all cases.

After the appointment, Clough and his wife sat inside their van and prayed. They thanked God for giving them an answer after months of diagnostic tests.

“I think that’s about the only time I’ve cried for myself,” Clough said.

But Clough gets emotional when it comes to his wife. He removed his glasses and wiped away tears as he talked about her taking on the role of his caregiver.

“That’s the thing I hate the most is that she doesn’t deserve this, to have to take care of someone,” he said. “I hate seeing her tired and hurt.”

Celebrating Life

Clough met Karen through his church and proposed to her on Camelback Mountain. The two were married on Nov. 29, 1997.

“Three and a half years ago, we were asked to do a documentary with Arizona State University,” Clough said. “In that documentary, she said, ‘We don’t even know if we’re going to make it to our 20th year anniversary.’ But it looks like we are.”

They’re planning a trip in March to celebrate.

Clough is a father to three grown kids and is expecting his eighth grandchild in January. He wants to leave a legacy of enjoying life to the fullest—a legacy he hopes his kids and grandkids will continue.

Clough believes his contributions to the ALS community and his positive attitude are extending his life. At the very least, he said helping people brings him joy in the time he has left.

For others who are coping with a difficult diagnosis, Clough offers this advice: “Own your life and have fun. Do what you want to do because if you don’t, you’re short-changing yourself. I would say that not just for people who have ALS but for everyone.”

In other words: love life, live life.